Dali Museum in Figueres, Spain. CC BY-SA 3.0 <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/>, via Wikimedia Commons

Which Came First- the Chicken or the Egg?

by Lorette C. Luzajic

If you’re in the habit of wandering around Catalonia, you’re not likely surprised to find artistic and architectural oddities in the clouds. Catalan, Spain, is historic home to a number of flamboyant surrealist, modernista creatives, from the spindly stars and forks of Miro sculptures to Picasso everything. The skyline is synonymous with Antoni Gaudi’s eclectic mosaic of colourful broken tiles, of towering spires and spirals twirling atop the trees. Gaudi had no rival when it came to offbeat beauty- but another artist of sui generis (“one of a kind”) spirit outdid him in weird: Salvador Dali. And if Barcelona belongs to Gaudi, Figueres is Dali’s world, birthplace and burial of the great surrealist, a place surrounded by giant…eggs.

Yes, eggs. Like the magnificent Moai standing guard around Easter Island, Dali’s museum rooftop is a fortress surrounded by massive eggs. The nearby Casa Dali is also topped by a colossal egg. Approaching the Costa Brava from the Mediterranean, it would appear strange and ghostly, like a surreal lighthouse.

Salvador Dali had a thing for eggs.

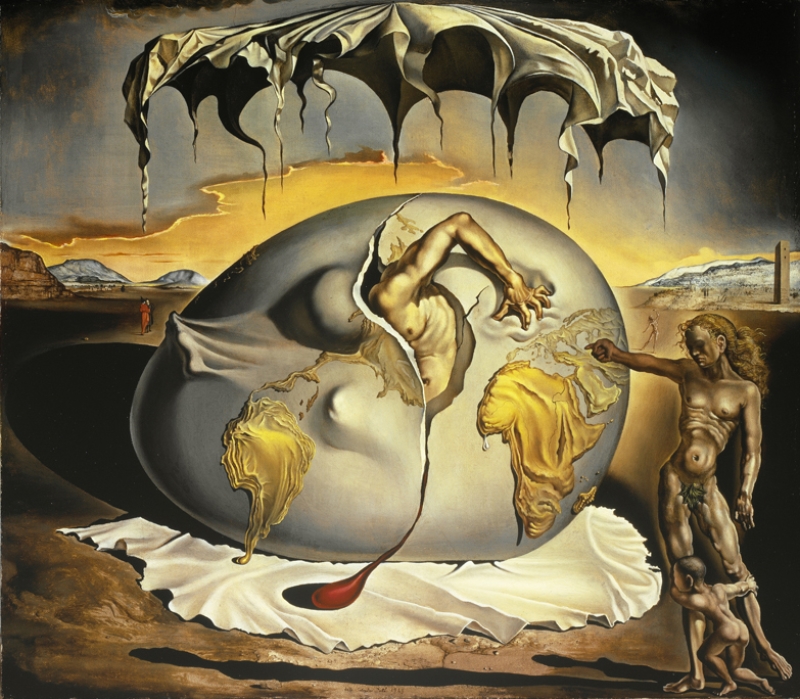

Geopoliticus Child Watching the Birth of the New Man, by Salvador Dali

They turn up again and again in countless paintings and sculptures, including Fried Eggs on a Plate Without the Plate in 1932, with the eggs echoing the previous year’s infamous melting clocks. His 1943 work, Geopoliticus Child Watching the Birth of the New Man, showed a man struggling to come out of an egg. The complex classic Metamorphosis of Narcissus (1937) prominently featured an egg growing a lily. A painting of a telephone receiver communing with fried eggs appeared in his cookbook of surreal gastronomy, Les Diners de Gala, which also featured recipes for Thousand Year Eggs and Spit Roast Eggs, to name a few.

Dali was surrealism personified- or perhaps, theatricized. It was an art movement born in the Freudian era, where the unconscious was the key to the universe. Surrealism was a rejection of rationality, after artists had had a little too much enlightenment and wanted to bring back some mystery. It acknowledged archetypal and personal symbolism, accepting the psychoanalytic belief that the unconscious mind was bigger and more important than we had ever imagined.

“I am hallucinogenic,” Dali declared, with characteristic humility.

But what was with the eggs?

The egg is almost as packed with symbolism as it is with nutrients. In Australian aboriginal Dreamtime, the egg symbolizes light. The egg yolk was a symbol of the sun in ancient Egypt, and Ra, the sun god, was hatched from a cosmic egg. The Hindu Upanishads liken all of creation to a version of this cosmic egg- life on earth is the yolk, and the heavens are the outer layer. In classical western mythology and pagan history, the egg is a popular motif signifying fertility, birth, and nature. In Christianity, particularly eastern or orthodox interpretations, the egg is sacred, signifying life, rebirth, and resurrection. Other traditions and renditions point to luck, life, wealth, sexuality, reincarnation, nourishment, and more.

For Dali, it was all these things that made the egg a recurring emblem of his art. In his own notes, he wrote of the egg in one of his works, “Parachute, paranaissance, protection, cupola, placenta, Catholicism, egg, earthly distortion, biological ellipse. Geography changes its skin in historic germination.” We may also speculate that the egg was tied up with his professed belief in intrauterine memory- Dali insisted he could remember everything, including his time in the womb. This may be tied to his idea that he was born before or again, as his older brother who died at two, and shared his name.

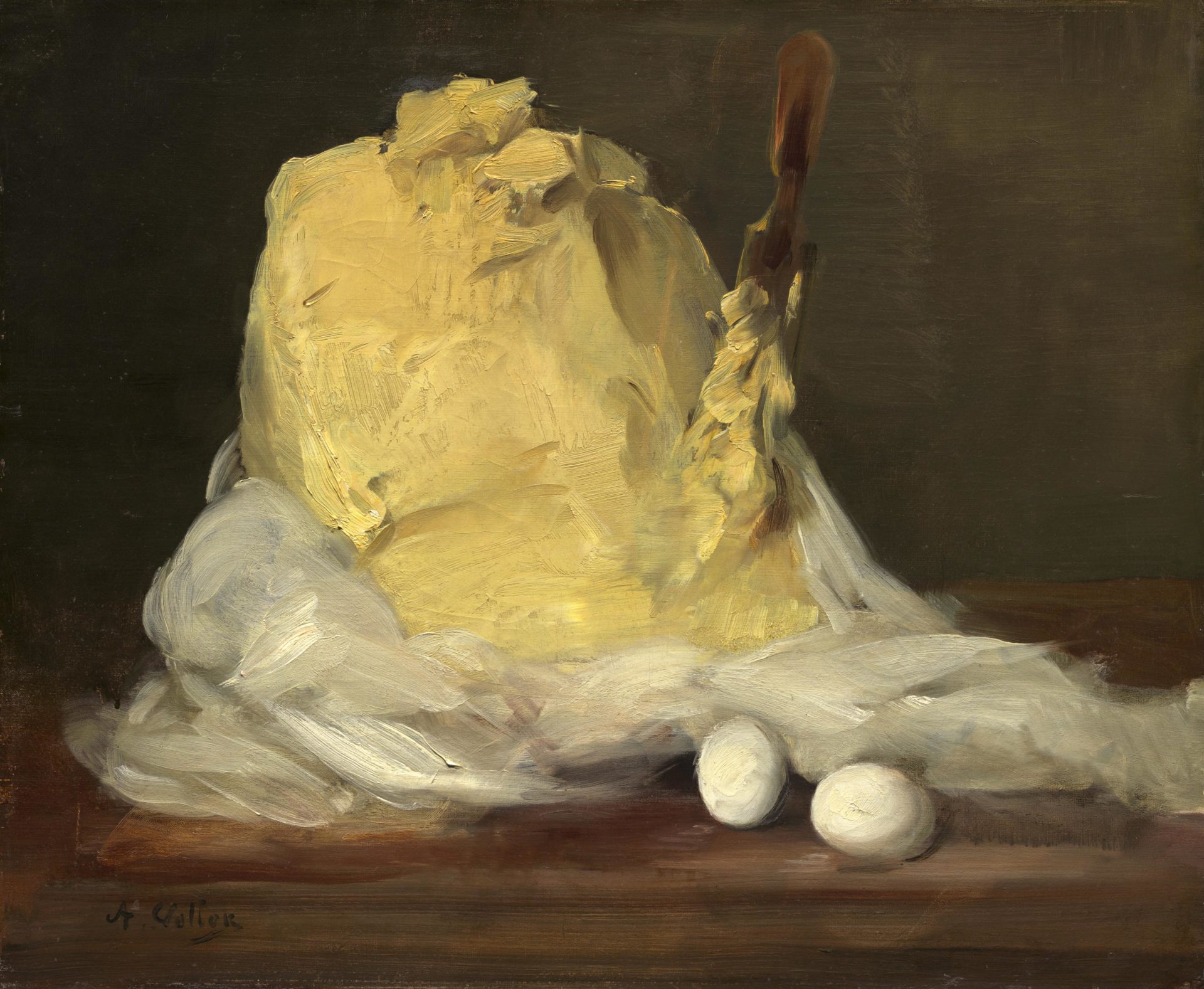

In any event, Dali is not the only artist who employs the egg as a cosmic symbol. It recurs regularly in fellow surrealist Magritte’s work, mystic saint Hildegard Von Bingen’s art of the middle ages, and Hieronymus Bosch’s medieval metaphysical masterpieces. Eggs were a recurring motif in the still life works of Antoine Vollon, most memorably perhaps in the French realist’s “Mound of Butter” painting.

Mound of Butter, by Antoine Vollon

The egg featured frequently in “egg dance” paintings in European art around the 16th century. Modern audiences may wonder about the peculiar depictions of peasants whooping it up in taverns with an egg on the floor, until we understand such works are warnings that “breaking the egg” will make all hell break loose. The egg represents sexual propriety. There were a variety of elaborate folk traditions that involved rolling an egg, or dancing over a number of placed eggs, with the challenge to leave them in tact. Other egg dances were for couples- if the egg didn’t break, you were meant to marry.

Old Woman Cooking Eggs, by Diego Velazquez

Perhaps the most spectacular appearance eggs make in art is in Diego Velazquez’s Old Woman Cooking Eggs, 1618. With chiaroscuro even more intense than Caravaggio, Velazquez’s sublime work contrasts the dark space with the white, brass, and glass. Although most Spanish “bodegone” genre paintings include only foodstuffs, not people, this one usually gets classified with them. Such works often acted as “commercials” for their artists, showing off their incredible techniques in hopes of attracting clients. Paintings metallics and transparency and such vivid realism was no easy task with such a limited palette of the day, but this piece is all the more remarkable because the artist was merely 18 or 19 at the time. He was swept up by the king just a few years afterwards, where he spent his life as a painter in the service of the royal courts.

Folk art traditions with eggs are even more common than fine art ones. While millions of us may be decorating hardboiled eggs soon with everything from Crayola markers to Jello dye to Paw Patrol Easter egg sticker kits, these rites run quite ancient and across cultural lines. The oldest decorated eggs we know of are from South Africa, estimated to be 60 thousand years old. Museums hold a number of decorated ostrich eggs, including Punic painted eggs from Tunisia. Handmade clay eggs were found in King Tut’s tomb in Egypt. Throughout classical Rome and Greece, eggs were used in pagan cultures to celebrate the spring equinox, symbols of fertility, life, and light.

Mesopotamia and neighbouring worlds had many spring festivals as well with various customs that included eggs. The celebration of Nowruz at the vernal equinox has its roots in Zoroastrianism and ancient Persia, and includes an egg decorating ritual that is more than 4000 years old! The Haftsin altar includes candles, garlic, fruit, and flowers, and exquisitely painted eggs. They symbolize fertility and hope. The New Year’s eve ritual, ChahaShanbe Soori, includes gifts of eggs and breaking eggs.

Decorating eggs is an essential aspect of many eastern orthodox cultures. In Greece and beyond, eggs are dyed or painted red, often naturally with beets or onion skins. The red signifies the sacrifice of Christ and his suffering, and the gift of life through his.

Easter Eggs in Macedonia. Petar Milošević, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

In traditional Balkan egg decorating, all Easter eggs are red. Natural dyes are used, along with various leaves wrapped for stunning patterns. A popular technique was scratching of patterns to reveal the white shell underneath the colour. The first red egg was the “Čuvarkuća” or guardian, and was to be left in the home until the following year. The red egg represented Christ, life, hope, resurrection, and God’s power, but such customs also have an old folk life- eggs absorb negative energy or evil spirits, so an egg in the home or in the crop field is a double blessing.

Incidentally, oomancy, or the practice of fortune telling from reading a broken egg, is an ancient art still practiced in Greece, the Balkans, Poland, Germany, Norway, Scotland and more. Related egg magic take place in Africa, in Haitian voodoo and its sister practices the Caribbean and Americas, One widely used technique is to use an egg to absorb a person’s energy, then to crack it for reading. The oomancer will know whether the person is victim to the evil eye.

Painted Urkainian Easter Eggs, Pysanky Museum, Kolomiya, Ukraine- photo by Adam Jones (CC BY 2.0)

Decorating eggs is very important in Ukrainian culture, with archeological evidence of painted prehistoric ceramic eggs. The folk beliefs held that beautiful eggs would ward off evil, and although the traditions later absorbed Christian symbolism, the pysanky are still “good luck.” Intricate and elaborate, Ukrainian pysanky are painstakingly painted after initial hand-drawing, using batik or wax resist methods. Pysanky are given to others as a gesture of friendship and community.

Easter egg painting is just as rich a custom in Catholic and Protestant traditions. Poland is well known for incredible folk art pysanky in numerous styles. Germany is known for decorating trees, fountains, and other public structures with painted eggs. The Easter egg tree is an ancient rite whose origin is obscured by the centuries, but the practice is going strong and has spread to German influenced or German speaking regions including Switzerland, Pennsylvania, Poland, etc. One tree was famous for hanging 10 000 painted eggs, and another for 76 000! Smaller tabletop trees inside are a popular ritual to hang heirloom eggs each year.

Easter Egg Tree, Germany. Kora27, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

It is fascinating that eggs have been so widely symbolic of both magic and sustenance, across time and cultures.

Today they are emerging from many decades of misinformation wars against the egg, vilifying it for saturated fat and cholesterol content, both essential to human health. In 1968 the American Heart Association fingered eggs as a deadly villain, quietly dissolving its anti-egg guidelines in 2015.

The powerhouse egg delivers a complete protein along with Vitamins A, D, E, K, K2, the B complex, selenium, phosphorus, iodine, lutein, betaine, manganese, iron, choline, zeaxanthin, magnesium, potassium, and zinc- to name a few.

While our current model of factory farming is hell for millions of chicks and the quality we consume from their production, the natural egg is an unparalleled gift of nutrition. It is valued world-wide as an economical food solution. Nothing else has as complete a profile of vitamins and minerals as the egg! Most commonly in the contemporary west we consume chicken eggs, and lots of them- in 2020, nearly 87 million metric tonnes of eggs were produced, estimated at around two trillion individual eggs.

When we think of eggs, most of us think of chickens. But many eggs are eaten around the world, including duck eggs, turkey eggs, quail eggs, and fish eggs- otherwise known as caviar and roe. An ancient Aztec superfood is ahuatl, or “seeds of joy,” the eggs of the water fly. Traditional food markets will have heaps of them, dried or toasted. They look like rounder sesame seeds.

There are so many classic egg dishes around the world that we would need an ongoing blog or an encyclopedia to cover them. Less familiar egg recipes are limitless- most countries have dozens, if not hundreds. From the sunny side up breakfast to the Denver (“the western”) to India’s Anda Bhurji, eggs provide tasty and affordable fuel. The egg McMuffin breakfast sandwich is everyone’s guilty pleasure, selling a whopping 255 million every year.

Bibimbap, by superturtle, CC BY 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Bibimbap is the delectable Korean classic of mixed rice in a hot stone dish, with savoury meats, kimchi, and gochujang (sweet chile paste) and a poached or pan fried egg on top. The makhlama lahm (“meat omelette”) is a delicious parallel in Iraq, ground lamb and yellow curry with mixed diced vegetables with a crowning egg. It first appeared in a tenth century Mesopotamian cookbook! Eggs Florentine is the most beautiful brunch, gooey spinach and egg and Hollandaise sauce on a biscuit or muffin base. The pickled egg is a pub staple in traditional taverns from Scotland to Denmark. Huevos divorciados is one of my personal favourites, a Mexican star featuring eggs in salsa rojo on one side of the plate and eggs in salsa verde (red and green sauces) on the other.

Eggs khageena are a delicious Pakistani version of scrambled eggs with spicy chiles. Chinese egg drop soup features silky strands of egg and tofu with scallions in chicken broth. And century eggs, the inspiration for Salvador Dali’s Thousand Year Eggs, are also known as black eggs. They are preserved in clay, quicklime, ash, salt, and rice husks, usually for weeks or months, not 100 years or 1000!

If you find yourself in Dali’s Catalonia, you’re more likely to find yourself munching on ous estrellats, a popular treat at countless tapas restaurants. This is basically patatas bravas- fried potatoes- with scrambled eggs, spices, and some succulent morsels of serrano ham.

In solving the age old philosophical dilemma- what came first, the chicken or the egg?- should we turn again to Dali for insight? At least, perhaps, he can help us understand his surrealistic fixation on eggs. Remember for a moment his claim to intrauterine memory. In The Secret Life of Salvador Dali, he wrote about these memories: “…The most impressive sight was that of scrambled eggs, without the pan; this probably disturbed me for life.”

Century Eggs, China. FotoosVanRobin from Netherlands, CC BY-SA 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0>, via Wikimedia Commons