“…And again I wondered to see how the brewery was right outside the town, how it was surrounded all round by a wall, with the little town on the other side, but how along the walls there are tall trees of maple and ash, which also form a square shape, and how this brewery resembled a monastery or a kind of fortress, or prison, how every wall was topped not only with barbed wire, but each and every wall and pillar had set in concrete on its topmost bricks jagged fragments of green bottles, which glittered from above like amethysts and amaranths.”

-Bohumil Hrabal, Cutting It Short.

I’m standing on a bridge in the town of Havlíčkův Brod, watching the nearly imperceptible flow of the Sázava river past banks on which stand willows that are developing their first show of colour in the late March evening. In several places as I have walked along, performing the odd errand, pieces of the town’s mediaeval fortifications have been visible as the boundary of a path between modern apartment buildings or even incorporated into children’s playgrounds. In the town square, under the clock, the figure of the grim reaper stands, commemorating a military betrayal 550 years previous when the gates were opened to the enemy from within.

This brief moment of reflection comes in the middle of a whirlwind tour sponsored by the Czech Government. I had said to a senior diplomat at a Budvar event at Toronto’s Godspeed Brewing that I did not understand the beer culture of the Czech Republic. I knew that the beer was excellent and that the taps were different, but that I didn’t understand why. “You should come to the Czech Republic,” came the answer, and here, several months later, was a crash course.

The Czechs drink more beer per capita than any other nation on the planet. Beer may not be universally cheaper than water, but it is certainly less expensive than coffee. The figures for 2020, something like 181 litres per capita, are probably aberrant because of the time spent in lockdown without much to do. The more conservative figure from 2019, 140 litres per capita, is still nearly three times the volume consumed in Canada, and about thirty litres higher than the next country on the list, neighbouring Austria. They produce the same amount of beer as Canada, despite having just under a third of the population. The country is about a 14th the size of Ontario.

In Canada, it has been the darkest winter in eighty years, so the play of light across the rolling hills of Bohemia and the depth of greenery feels luxurious despite the chill in the air. As the bus meanders through the countryside, I’m struck by the immediate delineation of town and field. There is no sprawl, and each carefully manicured hectare of spruce will eventually be mustered for lumber or fuel in a careful cycle of plantation. Lining the streets and verges, cherry trees are in bloom. In the centre of each small town we pass, there’s a simple Baroque church and a slightly simpler tavern.

It’s on that basis that the robustness of Czech beer culture is perhaps best understood. The towns are isolated, and for that reason must have had, to some extent, to fend for themselves. While the traditional Lands of the Bohemian Crown have passed under different control over the last thousand years, the land surrounding the towns is largely immutable regardless of who is nominally in control of it. There’s no room for error in a finite system, and even on a cursory visual inspection, the precision of the landscape speaks to intentionality.

Starting in the 13th century, larger towns were given the designation of Royal Cities. This meant being given trade rights which included brewing. While the location and number of breweries has changed over the intervening 800 years, the expectation that each town produces beer was fundamental. By 1517, just a year after the Reinheitsgebot in neighbouring Bavaria, tapping rights were split to include the nobility. By 1848, anyone could set up a brewery by paying for the right. By 1869, well into the industrialization of the country, anyone could open a brewery.

Despite shifting borders, the geography is immutable. Because they’re typically associated with a Royal City, the breweries are infrequently named after a person. As they represent the collective brewing rights of a number of individuals, the beer had better satisfy those individuals. Looking at breweries of the same era in North America, they’re purely capitalistic endeavours, typically named after the founding family, and void of the sense of communal purpose one finds in the origin stories of Czech breweries.

If your town wanted good beer to drink, you had to come together and make it happen. The Czech people, sensibly, made this a priority.

For a hundred and fifty years, in a cellar in Benešov, a man with a rake has trodden up and back, up and back along carefully ordered rows of germinating barley nearly six inches deep. The slick slate floor mimics earth the kernels would find themselves in had the grasses been left to go to seed. The maltster pulls the rake with a practised motion long committed to muscle memory, stepping backwards while pulling with his upper back and triceps, rowing through the barley and leaving a patterned wake at three foot intervals.

The low vaulted ceiling allows for temperature and humidity control year round, and the dim light could lend a cthonic, sepulchral connotation to the proceedings, except that this is life in creation. The barley must be turned so that the roots do not bind together, so that the temperature generated by its mass does not impede its progress, so that it can breathe. At this point, it tastes like a combination of edamame and wet hay. As it nears its potential, preparing to sprout into a new plant, it will be shovelled into the maltster’s cart and arrested by the gentle heat of a drying kiln in another part of the building.

The Czech Republic has six such facilities. The barley, for the most part, comes from the southeast in Moravia and has been derived at some point from an older strain called Haná. At 250,000 acres, it makes up nearly a twentieth of Moravia’s total area. While the harvest is now mechanised, the floor malting process is unchanged since 1887 when the facility was purchased by the Archduke Franz Ferdinand d’Este.

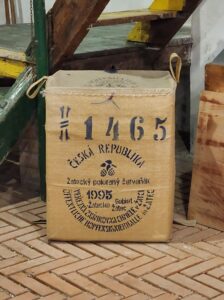

Pivovar Ferdinand produces 2,200 tonnes of malt a year, of which they use only 450 to make their beer. If you’ve ever tasted a beer made with Weyermann’s Bohemian Floor Malt, this is where it came from. The mounds of barley that take their shape amongst the rough timber beams of the building take on a familiar sweet cereal aroma after they’ve been dried, and barley flour clings to your clothing if you lean on the wall to take in the scent.

Is it possible to impart a soul to barley simply through repetition of a difficult task? Is the care taken in that three foot stroke, repeated infinitely by a succession of people in the aid of something that will bring people joy enough? Does the strain in the lower back with the weight of the shovel, the ache in your shoulder, impart meaning? Is it any wonder the motto dej Bůh štěstí, “May God Give You Happiness,” adorns the walls of the breweries and malthouses?

In the royal city of Žatec, there’s evidence of the centuries of shifting control in the name of its most famous export. Saaz is not merely the hop variety, but what the Germans call Žatec. It’s hard to think that a yard of beautiful yellow flowers could outlast temporal governments, entire modes of governance, but Saaz is a land race hop that has persevered from the middle ages.

In some parts of the world, the focus is on novelty; on the development of new varieties of hops, frequently numbered and without names, developing myrcene rich essential oils that contribute stone fruit, tropical fruit, bright citrus. In Žatec, the order of the day is allowing Saaz to retain its character, dependent largely on farnesene, an essential oil that is the hallmark of the strain.

Climate change is a pressing issue for brewers across the world, with low barley yields increasing costs and changes in weather patterns increasing temperature and drought. I have rubbed Saaz hops over the last few years, and the alpha acidity is lower than it has been historically. There’s a slight eucalyptic, thymol herbal quality that has not always been there.

Bohemia Top Hop is on the case, attempting to create a Saaz plant that is better able to withstand a harsher summer of growth. Sitting in front of a laboratory fume hood, hands moving with incredible precision, a woman is delicately placing seedlings into dishes of nutrients and agar at a rate that seems astonishing to my untrained hands. The seedling will become a rhizome eventually, perhaps a year from now, developing a root structure before its shoots emerge from the soil.

In late March, we are at the wrong end of the growing season for majestic vistas of greenery stretching off into the distance. March comes with toil. The hop yards are strung and the wire that the bines will ascend in the summer as the sun trails across the sky needs to be placed. The hops themselves will need to be trained, if only gently, towards the wire.

Prior to the introduction of industrial equipment, 200,000 labourers would descend upon the hop fields of the Czech Republic, whether in Žatec or elsewhere, sleeping in barns and farmers’ outbuildings in aid of the hop harvest. Currently the harvest still requires 4,000 labourers.

Two weeks a year, three percent of the population of the country would harvest Saaz. The subtle irritation of the bine prickles, the welts between your fingers, the wet dirt on your knees would have been a near universal experience. The aroma of the Saaz hops in situ, green and peppery with a hint of chamomile florality, a spritz of lemony citrus oil, and that underlying musk of woody myrrh-like resin, would have been a national sense memory.

Despite the fact that the warehouse sits empty, waiting for the harvest in August later this summer, you can taste the air. The bitter perfume of the bales that were processed last year have left an echo, and its potency is such that any exposed skin begins subtly to itch. The hops are pelletized here into a few different formats before they are shipped across the world.

Pilsner Urquell is lauded internationally, and rightly so. The beer has spawned more imitators since its inception in 1842 than any other brewery could hope to. The combination of Pilsner malt, a treatment invented for purpose on site, with hops from Žatec and the soft minerality of Plzeň’s local water has been much remarked on. The brewery itself, making some 10,000,000 hL a year across all of its owned brands, is an incredible anachronism despite recent modernizations. They make Pilsner. Everyone else makes Pale Lager.

Our guide, brewmaster emeritus Václav Berka, is keen to show us the malt house. One technological step above Pivovar Ferdinand’s rake and shovel is the Saladin Box. Pilsner Urquell makes their own malt at the rate of 88,000 tonnes a year. It is steeped in conical vats fifteen feet across and released 200 tonnes at a time into a six foot deep trough with a grated bottom that blows air to control carbon dioxide from the grains. An arm, fitted with paired conical screws does the job of the maltster, raising the barley at the bottom to the top of the batch on each twelve hour pass. The room smells creamy, as though some precursor to diacetyl is detectable at that concentration of biomass. The maltster, Jakub, is kind enough to confirm this for me, explaining that it is knocked down in kilning.

The malt is under-modified by the standards of North American brewing, a fact which seems to sit in a pleasing circular logic. The malt will be decocted when it is mashed, a process that aims to convert as much starch as possible into sugar for the wort by gradually heating the mash to ensure all the enzymes are activated. If the malt were more modified, you wouldn’t need to decoct, but since Pilsner Urquell is by definition triple decocted, the malt must be under-modified. To change the flavour profile 181 years in would defeat the purpose.

The copper kettle, 600 hL in size, is heated with direct fire at 700 degrees, taking the wort and darkening it in colour to the burnished gold that so captivated the world in the 1840’s. The Saaz hops provide bitterness and complexity and the caramelization provided by the decoction darkens the sugared cereal body to a rich honeyed sweetness.

While the brewery started in 1842, the construction of the cellars began three years earlier. Underneath the brewery, carved by hand into sandstone over the course of fifty years, each mattock stroke and barrowload eventually amounting to nine kilometers of purpose built cellar space into which thousands of 4,000 hL wooden barrels lined with pitch would find their way.

Although the amount of lagering time seems to have varied historically, I’m looking at traditional open fermentation in a wooden vat and pitch lined barrels used for secondary fermentation that we are sampling out of. In its unfiltered, unpasteurized state, even at four to five weeks of lagering, Pilsner Urquell is a marvel. Lower in carbonation than the draught version, with a bitter sting in its tail that prompts the drinker to thirst for another mouthful, it is, without question, the real thing.

As we’re sitting down to lunch, knowing that I have only so much time to ask questions, I am thinking about another anachronism. I have been told that the Czech Republic is one of the most atheistic countries on the planet. But here is also an unbroken tradition. How many miles of raked malt, how many hands left with bine welts and nicks from the hop knife? How many swings of the pick? How many planks planed and bent for staves for iron hoops? And in aid of all this, at the point where all of this activity comes together, in nearly every brewhouse and malthouse and cooperage is a cross and the invocation dej Bůh štěstí, “may God give you happiness.”

In the following week, Pilsner Urquell will send 2023 bottles of a specially blessed beer to the Vatican. In their new facility, Proud, there is a bell blessed by the Pope that they ring at the end of each brew. On their tour are chalices that were specially designed as Papal gifts.

“Václav, I notice that most of the breweries I’ve been in have the motto dej Bůh štěstí placed somewhere. How seriously do you take that?”

“Well,” said the brewmaster emeritus, “we’re not in control of everything.”

To be continued in Part Two.