Viva la Vida: Why Watermelon is the Meaning of Life

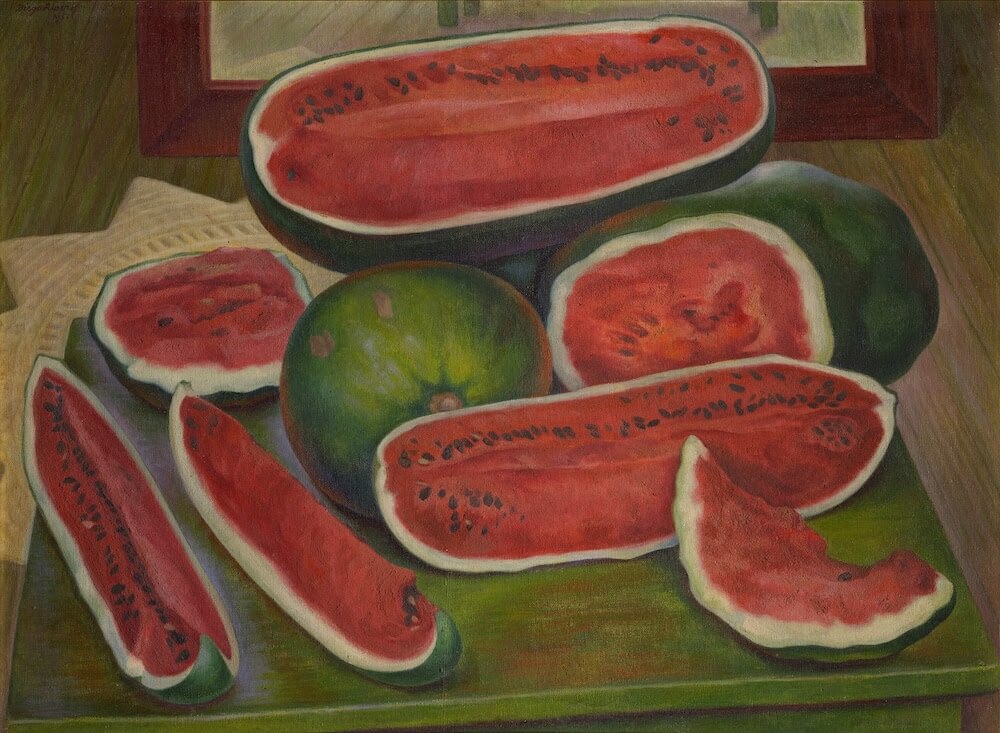

In 1954, a week before she died at the age of 47, Frida Kahlo finished her final artwork, giving it to her husband, the artist Diego Rivera. It was much different from her usual style, drawing on Mexican ex-voto traditions and incorporating personal and cultural symbolism surrounding self-portraiture. This piece was a still-life, close-up, of juicy watermelons, with whole fruit and sliced fruit arranged together. Inscribed boldly in the flesh of the front and centre slab of red pulp are the words “viva la vida,” or “long live life.”

Watermelons symbolized life and love, abundance and fertility, and were popularly used in Mexico’s Dia de los Muertos (Day of the Dead) celebration imagery and altar offerings. Many Mexican artists chose the subject, honouring folk culture traditions that saw fecundity and promise in the big red fruit. It could grow with very little moisture and nonetheless give relief to the thirsty, and the seeds would carry out life beyond its time.

Although the official cause of Kahlo’s death was a pulmonary embolism due to pneumonia, some read the watermelon painting as a suicide note. It accompanied the gift of a ring for the couple’s silver anniversary, given to Diego the night of her death. When he asked her why she was early for the occasion, she said, “I feel I am going to leave you very soon.” Her last journal entry reads, “I hope the exit is joyful and I hope never to come back.”

It is likely that Frida understood that her lifelong battle with illness was coming to a close, and her actions can be interpreted in that light. She had famously survived polio, dozens of broken bones in a streetcar crash, spinal cord injuries, multiple miscarriages, severed toes, and finally, a leg amputation. Perhaps she knew the curtain was closing.

But perhaps she had simply had enough of the pain. Frida had attempted suicide several times already, by hanging and by overdose. She was depressed and Demerol injections to battle the agony were a hell of their own. It is entirely plausible that Diego, who loved her madly despite their volatile relationship, covered for her. He was fiercely protective of her. He was the one who arranged a doctor friend of his to make up the death certificate.

He later said Frida’s death was “the most tragic day of my life. I had lost my beloved Frida forever–Too late now I realized that the most wonderful part of my life had been my love for Frida.” While the reports from others at her funeral that in his despair, he scooped up a handful of her ashes after the cremation and put them in his mouth may seem farfetched, both lovers were notorious for outrageous, dramatic acts of passion. Diego died three years after she did, some say of his broken heart. The great muralist of Mexico’s last painting was also uncharacteristic of his usual oeuvre: it was a still life of watermelon.

Las Sandias, by Diego Rivera (Mexico) 1957

The message was clear, from both of them- they loved life, despite all the suffering and difficulty inherent in living. If the symbolism wasn’t clear on its own, Frida made sure we knew what she was saying with those words “viva la vida.”

Watermelon is a large fruit loved across the Americas, Africa, Europe, China, Australia, and beyond. Also called the Citrullus lanatus, it is a cousin to squash, cucumbers, pumpkins, and cantaloupe. It has a tough green rind, hard white flesh, and soft juicy red flesh (some varieties are yellow) enmeshed with black seeds. It is exceptionally refreshing, as it is over 90% water. Most of what remains is sugar, along with the goodness of lycopene and citrulline, and a little potassium, Vitamin C, beta carotene, and copper. In recent years, the food’s potential contribution to virility has come to the scientific fore. The citrulline is an essential element in sexual health and circulation, though the reputation with fertility, abundance and life is much older.

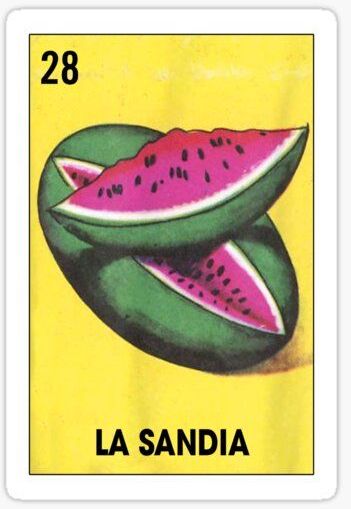

Though the Riveras personified the passion, intensity, and tenacity of all that the watermelon symbolized, the fruit was a recurring theme for other Mexican artists, like Rufino Tamaya, who made a variety of portraits of people eating watermelons. (It is a subject in art history in Iraq, Korea, Colombia, Algeria, and beyond!) Production of the giant and beloved berry was and is an important crop in Mexico, with 1.3 million tonnes annually (which is nothing compared to China, which grows more than half of the world’s watermelons.) Watermelon is widely eaten as a street food, sprinkled with chilli and lime, and common in salads as well. It is even one of the symbols in the popular loteria card game of chance.

But unlike many other favourite fruits like the avocado and the tomato, the watermelon was not domesticated and cultivated by ingenious Aztec people and taken back to Europe by settlers. This time it was the other way around- European explorers (who got them from the Moors) and African slaves introduced the watermelon to the “New World.” If not South American, the watermelon is widely assumed to be an American fruit. Indeed, there are 100 thousand acres of watermelon farms, mostly in Georgia, Florida, California and Texas. We grow a few watermelons in Canada, too, right here in Ontario. But the watermelon is an ancient fruit with roots all over Africa.

Experts aren’t sure of the precise origin. Scientific classification of various melons is a bit of a mess, apparently, and has led to a few uncertainties and mishaps along the melon trajectory. This is all in a day’s work, of course, in botany and genetic research and archeology, where the stories of our past is always full of holes. Some place the earliest watermelons around South Africa, but more recent research looks more like Sudan.

Jithesh Sundar, CC BY-SA 4.0 Wikimedia Commons

What we know for sure is that watermelon is ancient. It is one of the earliest domesticated fruits. We know this because we have found domesticated seeds in 5000 year old tombs in Libya and Egypt, as well as paintings of melons in Egyptian tombs and beyond. We know that like most fruits, the early versions were not as sweet, and art history and botanical illustration reveal different iterations of flesh colouring and composition.

We know that watermelons grow heartily in a variety of climates, including the desert. The tsamma watermelon grows in the Kalahari Desert, named for the Tswana word meaning “the waterless place.” Desert peoples and animals often survive from the tsamma melons. The watermelon was widely valued because it was a means of storage for water in places of scarcity. This is one reason why the watermelon is sacred in many cultures and why it symbolizes life!

Tsamma Watermelons in Namibia Desert, 2017, photo by Olga Ernst & Hp.Baumeler, CC BY-SA 4.0 Wikimedia Commons

Since the fruit was so useful to desert dwellers from antiquity, for practical matters of hydration, a range of North African and Middle Eastern cuisine is made with watermelon as an ingredient. In North America we habitually eat watermelon straight up- cut into cubes or giant wedges and enjoyed fresh off the rind. But in various cultures of the Middle East and Mediterranean, you’ll find watermelon infused into many delicious recipes. Watermelon with halloumi cheese and mint; watermelon with goat cheese or feta; watermelon with tomatoes and harissa; watermelon with sumac. It is especially popular in Gaza. Palestinians love roasted watermelon salad, fatit ajir, also called Qursa or Muleela. Unripe young melons are roasted over a spit, then mashed with eggplants, squash, and peppers.

For Palestinians, a longstanding love of watermelon became an unexpected symbol of independence in recent times. The colours of Palestine’s flag are red, black, white and green- the same colours as watermelon- so artist Khaled Hourani seized on an idea for an art project of resistance. He began painting watermelons to signify Palestine itself, and watermelons began making viral appearances in art and graffiti, becoming part of popular culture much like Warhol’s iconic soup cans.

While the reverence of watermelon as life is a nearly universal symbol, closer to home we have a different history. Watermelon is associated with racism because of an ugly chapter in American history. Around 1870 and especially commonplace in the first half of the 20th century, a crude caricature of Black Americans centered around the watermelon. Postcards and editorial cartoons featured a peculiar stereotype. African-Americans were supposedly simpleminded and lazy because they loved watermelon? The illustration style, not to reproduced here, mocked Black people as simpletons with sloppy manners. And while it is mostly a thing of the past, thankfully, it reared its ugly head again when Obama became the first African-American president.

As with many kinds of fruit, in many parts of the world, the watermelon was also an important subject in art beyond these hateful cartoons. Unfortunately, it is a delicate subject just to look at any American paintings that show watermelons. American still life artists and portrait painters were just as likely to showcase watermelon as artists in Holland or the Middle East, because the food was essential to many, beautiful, and ripe with symbolism. One notable work was Cracked Watermelon, by Charles Ethan Porter in 1890. Porter was an important artist because he was the only African-American still life artist at the turn of last century.

Cracked Watermelon, by Charles Ethan Porter (USA) 1890

No one can quite figure out what the deal is with watermelon and how or why it figures into this racism. After all, people from every part of the world eat and love this juicy fruit. It’s an important part of agriculture and sustenance from Brazil to Kazakhstan to Korea to Namibia.

The most likely explanation is that the watermelon was a different symbol altogether before it came to signify racism and stupidity. In the years following abolition, many enterprising individuals and families grew and sold watermelon to support themselves. The fruit signified independence, sustenance, and freedom- life. Perhaps those losing power had to make a mockery out of this perseverance.

Long live life, indeed. The heat waves are coming. Cool off and hydrate with the sweet, fuchsia flesh of this ancient fruit. Vida la vida!

Lorette C. Luzajic

The Star Festival, by Utagawa Kuniyoshi (Japan) 1840

The Watermelon Seller, by Jawad Saleem 1953 Wikimedia Commons