Lorette C. Luzajic on drinking wine and making art in Tunisia.

You might have to go all the way to Tunisia to get a bottle of its wine, and you should.

The North African sky on the Mediterranean coast falls like a black cloak, and gazing upwards you can get lost in the night. Peeking through the deep forever darkness are a million faraway stars, pinpricks of shattered quartz falling from the lap of the moon. A faint, salty sweet perfume from the small grove of orange trees and the ocean tousles your hair with silky fingers. The rhythm of the waves is a lullabye.

Well, if ever there was one, this scenario called for another tumbler of rosé.

In a million ways, Tunisia is easy like Sunday morning. It was best to take off the watch and let my characteristic anxiety and punctuality dissolve into the ether. The country’s wine is as delicate, mild, moderate, gentle, soft, clement, and temperate as her soul. The people are easy-going and love to laugh, and with their mild-mannered ways and ready welcomes, you effortlessly feel at home. The faces are a full range of beautiful, from the richest bronze to the palest moon. Temperance is a virtue, and moderation on the side of generous is a way of life.

Tunisian wine is an ancient rite, as natural as the ripening of plump green olives under the sun, and the slow sauntering camels along the shore. Production began in antiquity with the Phoenicians and Romans. After Islam took root in the 7th century, wine making remained in the background, but never disappeared. The passion was revived during the French colonial years from 1881. After independence in 1956, there was a brief lull, but as hospitality and tourism became the nation’s main industry, the 21st century has seen a major increase in production and export, with rosé as the specialty.

Drinking in Tunisia is more about ambience and the ceremony of shared table than it is about the viticultural arts. You won’t hear Tunisians waxing philosophical about the wine, or murmuring between themselves in adjectives about bouquet or finish. Things here are both more free flowing, and more matter of fact.

The average consumption among locals is a paltry two litres a year, which sounds like about half a week’s supply. This number means two things: one, visitors provide most of the market, and two, many people abstain, but those who enjoy the fruits of the year round sun do so with great enthusiasm.

Most of Tunisia’s wine production is in rosé, and you should take your wine list cues from this reality. Forget huge, sinewy reds and forget the forgettable whites. Here you should sip on sunrise and sunset and the pink sands of the Sahara. Many of Tunisia’s pinks cap at eleven percent alcohol, which lets the faucet flow more liberally. In a country where everything starts two hours later, you can stop waiting and start sipping.

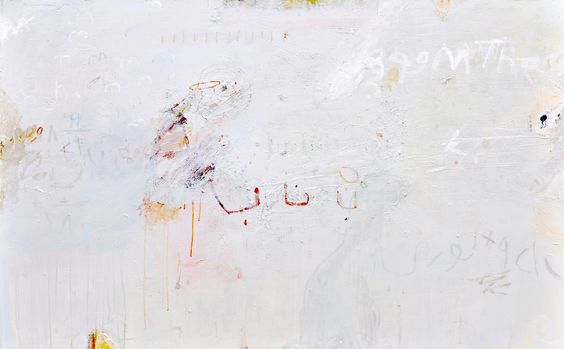

I found myself in the North African oasis of Tunisia last month thanks to a curious collision of fate. There was a note in my inbox from the Dutch-Iraqi artist Ali Rashid, whose achingly restrained abstracts (like the one above, used with his permission) broke my heart when I first discovered them. In the conceptual palimpsest his paintings embodied, and his use of the various on-hand tidbits of flotsam, I saw a kinship between us.

In the minimalism he employed, and in the gravitas of the experiences he endured, like war and exile, we were worlds apart.

But now here he was, inviting me to work with him and over thirty other contemporary artists from around the world, at the Symposium Méditérranéen des Ateliers d’Art Contemporain in Hammamet, Tunisia, Africa.

A couple of years ago, I had sent Dr. Rashid a brief essay I’d written about how I’d been moved by his works. We connected on Facebook, and he’d been following my work ever since.

Checking my email during a perimenopausal flash of insomnia at four-fourteen in the morning, I saw the email. Was I free in April?

I bound out of bed to make coffee, and fast. I needed cognitive faculties in tact, pronto, to process this turn of events. But by four thirty a.m., half an Elvis mug of instant java into the morning, things were plain as day. I was going to Tunisia, land of orange groves and pink sands to paint beside the crystal clear aquamarine sea.

I knew nothing of Tunisia, but dove into everything I could find before the sun came up. I spent the next weeks learning about one of the smallest countries on earth. For a fingernail strip of land, there was a colossal amount of ancient and modern history to immerse myself in.

Phoenicians, Romans, Arabs, Berber peoples and more had all made their marks here; and there were a thousand names of conquest or conciliation to sort through. More recently, the Arab spring ignited here, quite literally, when a soul in protest of tyranny set himself ablaze, pushing the first domino of the Middle East uprisings. The Tunisian artists I met later talked about the cities under siege and living in cars as the world turned upside down during the revolution.

Wedged dead centre of the north coast of Africa, between Algeria and Libya, and an hour’s flight from Italy over the water, Tunisia is an historic passageway of migration, trade, and military strategy. From Bible times to the New York Times, the nation is critically positioned a pebble’s toss from Europe. To the south, the desert, where caravans between worlds still intersect across eternity.

Also, historically, slaves. I stood in the souk – the market – in the old city that marked the spot where both black and white human beings were traded and sold. There were famous caravans in the 19th century that carried nothing but human cargo and gold.

And here were also, the artists.

From African and Asian tribal artists to ancient Roman sculptors to the curious European painters later called Orientalists, the centuries in Tunisia have been populated with the coming and going of artists. We have been drawn into inspiration by the history and mystery and rich tapestries of cultures converging in this magical place.

Here are the exquisite tile artisans whose legacy merged with indigenous arts as far away as Mexico. Here are nomads like the Berbers, whose grand jangle of jumble alloy metals seared over stone and coral has been praised far and wide in literature and couture. Here, the stunning expanse of sky and sea and sand conjured conjurers, painters who have never tired of trying to lay oiled pigment to the overwhelming beauty, wide and elemental, and nearly impossible to capture in brushstrokes or words.

Like them, I tried. I’m trying now. And failing utterly. You must go.

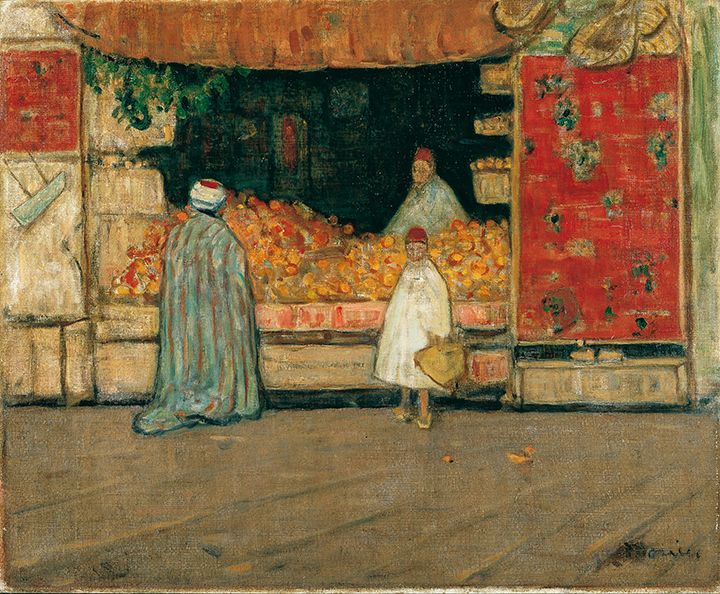

I met a man who did his graduate thesis on the Canadian painter James Wilson Morrice. Morrice was an early 20th century landscape painter who fell in love with Tunisia and returned again and again to paint it. There’s a room at the Art Gallery of Ontario dedicated to Morrice’s paintings. I’ve always loved the postcard size oil sketches he did. They have an assured, evocative charm to them. The Tunisia pieces were like tiny windows into another world, one I couldn’t have imagined I would find myself in one day.

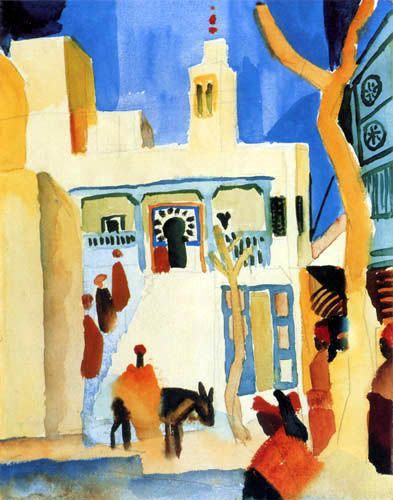

Other artists who flocked to Tunisia were more widely known, such as Paul Klee and August Macke (see above), European modernists who fell in love with the place. Their passion was noted on a few signs I saw throughout my journeys, including at Sidi Bou Said, an artist village in the capital, Tunis, preserved in the traditional blue and white.

Today all these forces converge to form a path for the most important art of all: the contemporary Tunisian scene.

I can’t possible have a thorough enough understanding of Tunisian art and history in my crash course to do justice to how now happened here.

Suffice it to say, artists are the past and the future voice of this beautiful, patient land and people. There’s a beating pulse of ultra new, raw, urban art voices in the graffiti and street scene- a movement that searches for the freedom and experimentation that we take for granted in Canada.

But artists here are not just rebels with a cause and some talent- they are also classically trained and work-obsessed, like the sculptors I met who carved,drilled, and sanded in marble from dawn until night fell. They study in Paris, or Madrid, or Rome, but those who stay at home receive just as intensive an education in classically important disciplines like history, technique, composition, and perspective.

I was amazed to find myself working next to so many brilliant painters and printers and sculptors. Despite a national personality that is unhurried, easygoing, and warm, art is a pursuit that is taken very seriously. Artists work hard, and insist on an intimate engagement with their audience. Art means something.

There was no stress whatsoever, but we worked every day, each of us producing in two short weeks several major works in our respective disciplines of painting, sculpture, or printmaking.

And every night after work, or even during it, afternoons – the wine.

I found Tunisians to be exceptionally receptive and open people with an astonishing talent for, or regard for, creativity. Despite the natural beauty of both women and men, despite the great talents and historical riches, despite the delicate nose of rosé, despite the gorgeous fiery harissa heaped on grilled meats, despite all these things of which to boast, no one was trying too hard or acting pretentious. No one had anything to prove.

Who can prove the moon and the sea, who can take credit for the startling navy depth of water and salt, or for the dance of the always sun and the meagre rain in the vineyards? Old women in the villages with herbs freshly torn from the earth will stop you, sure, and offer you magic orange water perfume that can apparently cure anything. And yes, some of the merchants in the medina are aggressive in trying to part you with your dollars for both cheap and worthy souvenirs.

But among dancing lanterns in the night, handsome hosts in white coats will beckon you in for fish and pink wine. Beyond these patios, the dark, broken by stars and faint music, and the sweet soft slapping sound of the sea.