This is a column about drinking and about (not) travelling and about terroir. It is about my journey to the Court of Master Sommeliers Advanced Exam and about the wines and beers and whiskies I taste along the way.

I am untravelled. I have not visited a single wine region outside of Canada. In the world of sommeliers and wine this is like being deaf. You can know all you want, read all you want, but the map is not the territory. If terroir is a sense of place as Matt Kramer famously observed, then how can a wine remind you of a place that you’ve never even seen, smelt, or touched? So, I drink the wine, and I imagine.

Recently, I had the opportunity to imagine what it’s like to be in Gigondas, in the Southern Rhône, 100km from the Mediterranean. Looking at a map, Gigondas is perched on an outcrop of rock, overlooking the wider river plain where Châteauneuf-du-Pape is found, 20 minutes away. Nestled in the foothills of the Dentelles de Montmirail, which itself is the beginning of the long climb up to Mont Ventoux, as many Tour de France fans know, Gigondas is widely considered the second cru, the little brother of Châteauneuf-du-Pape. But that hardly gives you a picture, does it?

Here, this is a picture of it I found on the internet.

So I am not in Gigondas but in the Summerhill LCBO, where Henri-Claude Amadieu of Pierre Amadieu wines is addressing a small group of media, a handful of sommeliers, and several wine writers of a certain vintage. The promise of a free lunch with wine has half-filled this small room. The atmosphere is “retirement-home-common-room”: quiet, relaxed, and somewhat confused. My neighbour’s loud tooth-sucking and lip-smacking will be forever immortalized on my tape recorder. Directly outside the window, two workers enjoy an hour-long chat and provide a near constant staccato stream of laughter as background music.

This is Henri-Caulde’s first time in Toronto and as the head of sales and marketing for his family it is his mission to communicate to those of us in the room who have not had the pleasure, just what it is like in Gigondas. He speaks of Mistral-days, of the 5km wide Rhône Valley to the north, of lavender fields to the south in Provence, of Grenache, king of the Southern Rhône grapes.

Henri-Claude is an elegant man, exactly how you might imagine a smartly dressed man should appear – Gallic nose, pressed two-button suit, white shirt, tie. Except he is not from Paris, he is from Gigondas; Gigondas, land of farmers and retired Roman legionnaires. Indeed, this 3rd generation vigneron appears in stark contrast to his forebears, of whom it was said, ‘they weren’t winemakers, they weren’t businessmen, they were farmers, paysans – and their life was much harder than ours’. Henri-Claude, along with his older cousin, Pierre (winemaker), his younger brother Jean-Marie (assistant winemaker), and his father, Claude (vineyard manager), run the family domaine their grandfather, the titular Pierre Amadieu, started in 1929. Despite his coiffed look, though, Henri-Claude was on a tractor as recently as two weeks ago. He has tried his hand at making wine, as well, but made too many errors and lost too much wine, so now, he is in charge of sales.

Indeed, this 3rd generation vigneron appears in stark contrast to his forebears, of whom it was said, ‘they weren’t winemakers, they weren’t businessmen, they were farmers, paysans – and their life was much harder than ours’. Henri-Claude, along with his older cousin, Pierre (winemaker), his younger brother Jean-Marie (assistant winemaker), and his father, Claude (vineyard manager), run the family domaine their grandfather, the titular Pierre Amadieu, started in 1929. Despite his coiffed look, though, Henri-Claude was on a tractor as recently as two weeks ago. He has tried his hand at making wine, as well, but made too many errors and lost too much wine, so now, he is in charge of sales.

The talk begins with a formal and technical tour of the Rhône before Henri-Claude relaxes enough to tell a few well-turned tales about Gigondas. He is a genial and polished speaker, his heavy Franco-inflected English clear and precise. When my neighbour repeats a question asked earlier, Henri-Claude gracefully elaborates another answer.

One story is where the name, Gigondas, comes from. This must be rote by now for Henri-Claude, because his tale is so smooth, you can only imagine he has worn all the edges off through turning it so often, like a galette, the round stones famous in the vineyards of Châteauneuf. Jucunditas – from Latin meaning joy, happiness, a place that’s nice to be – was the name given this settlement by the local Roman colony in nearby Orange, when Julius Caesar was granting land in Gaul to retired soldiers of the 2nd Legion, around 35 BC. Only a few years before, Caesar’s legions had been routed at this site by the fierce locals.

I can’t help but think of Asterix and Obelix and imagine an advertisement for a Happy Hills Retirement Home for Veterans in Jucunditas. Of course, one of the first things they did once these ex-legionnaires arrived was plant grapevines.

Henri-Claude turns another tale of how to pronounce the name Gigondas. When the Gigondais were simple farmers travelling to nearby villages and were asked ‘where are you from?’, depending on the harvest, if you had a good harvest, you would proudly say I am from Zhi-gon-DASS. However, if your harvest was so-so, you would perhaps mumble Zhi-gon-DA. Pronouncing the name of your village in a diminutive form is a password of sorts amongst locals throughout France, even while recognizing the proper way to say the name. (This is most interesting – JD, Editor)

But these stories don’t help us to get to Gigondas. Perhaps they only serve to keep us distant and at bay. What is it like there? Who are the people who live there?

It is a small place, a village of 500 people. 140 of them make wine. Henri-Claude jokes, basically everyone in the village makes wine except perhaps the couple who runs the bakery, which is also the grocer, which is also the newsstand, and the tobacconist, and the bank, and at night, the pizzeria. But it wasn’t always this way.

Most Gigondas families did not just grow grapes in the past, but practiced what many before them did and before monoculture took hold of our fields: multi-cropping. Henri-Claude tells how his grandfather, Pierre Amadieu, the son of simple farmers, grew up on a 7ha farm which was planted mostly with olive trees, but also a few vines. Pierre, however, was not interested in being a farmer and wished to become a professional musician.

He played the violin and toured the local fair circuit, playing for the crowds. When Pierre was 16 years old, he caught a serious lung infection. The doctor told his family that in order for him to be healthy, he needed to have regular physical activity outdoors. And what physical activity is more regular or en plein air than farming? So Pierre gave up his dreams of the violin and turned his artists spirit to the family farm. Inspired by the example of Burgundian vineyards, he decided to convert the entire farm over to a single crop, the grapevine.

Pierre Amadieu became a winemaker and a buyer and seller of wines, a negociant. He built his winery in the very heart of Gigondas itself, and made it big enough that he could handle the custom crush for most of the village, years before there was a cooperative. But there is more to this story. In neighbouring Châteauneuf-du-Pape at the time was a man named Baron Le Roy. This was the man who ended up co-founding the INAO, France’s governing body of wine, and essentially introducing the appellation system to France when Châteauneuf-du-Pape became the 1st Appellation d’Origine Contrôllée in 1936. A tireless promoter of the wines of his appellation, Baron Le Roy nonetheless also worked to ensure that no other wines of similar stature or kind from other villages nearby were promoted from the lowly Côtes-du-Rhône designation to the level of his beloved Châteauneuf. First and foremost, this meant Gigondas.  Pierre is famous as being the first vigneron to put the name Gigondas on the label of his wine, which was legally defined as Côtes-du-Rhône right up until 1971. I like to imagine that this was the violinist’s way of throwing a jeté at Baron Le Roy.

Pierre is famous as being the first vigneron to put the name Gigondas on the label of his wine, which was legally defined as Côtes-du-Rhône right up until 1971. I like to imagine that this was the violinist’s way of throwing a jeté at Baron Le Roy.

Today Amadieu holds roughly 10% of the vineyard area of Gigondas and is easily the largest vigneron in the AOC. You would be mistaken, though, in imagining that this was achieved through consolidation, as so many large winemakers do. Pierre Amadieu was fortunate enough to buy up an abandoned property in 1949 deep in the hills above the town. I say fortunate, because as climate change begins to alter the landscape and terroir of vineyards around the world now, winemakers are increasingly looking to higher altitudes and cooler climes. Henri-Claude’s face clouds over a moment as he relates that each year the harvest is earlier and earlier, even by a full month in his father’s memory. Under 14.5% abv barely exists anymore and everyone wants to plant higher up the mountain, where the Amadieus have been all along.

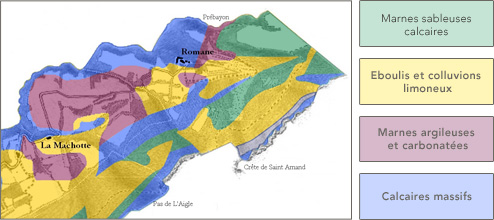

The land that Henri-Claude’s grandfather Pierre bought is a canyon between two arms of the Dentelles de Montmirail.

The “teeth of Montmirail” were formed in a sudden and violent upheaval. The once horizontal soil layers are now completely vertical and exposed. Centuries upon centuries of erosion by wind and rain have carved these jagged limestone cliffs into dramatic toothsome form 110m tall.

In 1952, Pierre cleared out the brush by putting 1,000 sheep along with 2 shepherds in the upper part of the canyon, La Romaine. In the summer they would head up to the Alps, and then back down to Gigondas in the winter where they would also leave behind some excellent fertilizer. During the trend for solving all of Nature’s challenges through the miracle of chemistry in the 60’s and 70’s, Pierre was busy planting grass to feed the sheep. This grass also helps to deter soil erosion, which is not an insignificant problem in the hills. The entire vineyard will slide downhill, vine and all, so that the straight rows you first planted are now more like s-shapes.

The canyon shields these vines from the Mistral, fiercely blowing on most of Gigondas, but it also creates its own gentler wind due to the altitude change within the canyon in the morning and the evening as the day warms and cools.

The canyon consists of two lieu-dits which provide two distinct bottlings. La Machotte is the first vineyard you reach on your way up the canyon from town. La Romaine, which was the site of a Roman settlement, lies further up the canyon. The old medieval buildings at La Machotte are used as Amadieu’s cellars.

And what of his descendants? Pierre, the Younger, Henri-Claude’s cousin, is the first in the family to have any formal training in winemaking and is the driving force behind new, ambitious bottlings. Previously, the fashion was for wines made from old vines and to put “vielles vignes” wherever you could on the label. Now, wines which reflect their terroir are the rage and so the current Pierre is focusing on vinifying all of the plots separately. His winemaking is for the most part traditional. Save for some use of new-ish oak barriques, Pierre is fermenting in concrete tanks and aging in massive 130 yr old foudres from Alsace. Interestingly, the Mourvedre undergoes malolactic fermentation, adding very delicate and perfumed aromas to the wine. Its strong skin can stand the intracellular fermentation while the Syrah is too fragile and delicate for this technique. A small portion of white wine is also made from Clairette, which the elder Pierre had a firm belief in, but is never blended into the red cuvées.

The original Pierre believed, like many in this part of the Rhône, in the innate supremacy of Grenache and Mourvedre to Syrah and planted accordingly. However, for the last few decades, Syrah has grown in plantings. Syrah is the light one from the North while Mourvedre is the dark one from the South and along with Grenache has thicker skins. The vines of Grenache and Mourvedre are left to grow untrained and planted gobelet, bush-style, (both are of Spanish descendancy), while the more thin-skinned Syrah is strung out along wires. The Syrah is always harvested first and is the grape which adds freshness and acidity to the wine. There is a smidgen of disdain remaining for this northern interloper, but also a grudging acceptance of what has elsewhere become one of the world’s most popular grape varieties.

In closing, Henri-Claude touches on the rivalry between Gigondas and Châteauneuf-du-Pape. He expresses the highest regard for the Châteauneuf expression of Grenache, but concludes, Gigondas is no longer considered its little brother, or even second fiddle. Indeed, it is simply an entirely different expression, and as far as C-d-P goes, “we do not play on this comparison anymore”. In a recent tasting of Southern Rhône wines, Alex Hunt MW noted, “it [Gigondas] needs to be considered very much equal, if in an engagingly opposite style, to Châteauneuf-du-Pape. It should be seen as neither Châteauneuf-du-Pape manqué nor Vacqueyras plus but on a level with Châteauneuf-du-Pape and offering a style that, as far as a Southern Rhône Grenache-based blend can be, is diametrically opposed. And that is its great raison d’être. It offers the drinker a very different expression of an ostensibly similar concept.”

And so, what of the wines? Gigondas is a wine born of the mountains. It is made principally from Grenache, and is overwhelming red, but is almost always a blended wine. It is a cooler, fresher, spicier expression of Grenache than that found down in the alluvial plain, but it is still a powerful wine. As one of the great tasters of Rhône wines, John Livingstone-Learmonth, remarked,  “Gigondas is marked by exemplary freshness and is capable of what I term Burgundian finesse, so it stands apart from its obviously robust neighbors … I think of Gigondas as one or two attributes. One of them is this very, very clear finish. You get what I call cendré, or ashy, pumice-stone notes as they finish”.

“Gigondas is marked by exemplary freshness and is capable of what I term Burgundian finesse, so it stands apart from its obviously robust neighbors … I think of Gigondas as one or two attributes. One of them is this very, very clear finish. You get what I call cendré, or ashy, pumice-stone notes as they finish”.

Power and freshness, these two noble qualities of fine wine which are often at odds, are here in Gigondas married. This is the hallmark of Gigondas Grenache, that it is fresher and spicier than its neighbours because of its altitude while still retaining that full body and high alcoholic power. But this fine-grained and mineral-driven wine is successful when you don’t notice the 14.5% abv, but instead are transported to a view and scent of these limestone hills.

Wines tasted:

Vinsobres Les Piallats Rouge 2012 – This ‘sober wine’ comes from one of the Southern Rhône’s most northerly AOCs. The Amadieus trade their grapes with other vignerons in the area and make this earthy, herbal-driven wine. 2012 was a warm vintage, delivering fruity, even jammy wines but this wine is more about crushed strawberry and thyme and retains a very pleasing iron minerality. 60/40 Grenache/Syrah $21 in Consignment (January) through Macdonald Wines and Spirits. Drink it up.![]()

Gigondas Romane Machotte Rouge 2012 – From the canyon, this wine displays dark brambly fruit, great acidity, and some pepper and spice. There is a floral and cassis note behind the fruit and spice and this wine finishes clear and precise. It seems like there might be more Syrah here, but in fact, it is 80/20 Grenache/Syrah. $27.95 Vintages #17400 only a tiny bit left in the system. Drink/Keep 3-5yrs.

Gigondas Domaine Grand Romane Rouge 2013 – This is the most modern expression of Grenache in this Amadieu lineup and also the prestige cuvée, and though it is closed, the use of new oak is evident. 2013 was a cooler vintage and a lot of Grenache was lost to coulure, so consequently this particular vintage leans more heavily on Syrah. The oak regime is 1/3 100hl foudre, 1/3 used barrique, and a 1/3 new. The Mourvedre really shines here, it’s carbonic treatment giving an almost Viognier-like lift. Bright red fruit, tannic, spicy from the barrel and the Grenache, this still is a very pretty wine. 60% Grenache 20% Mourvedre 20% Syrah $35 Drink/Keep 5-8 yrs![]()

Gigondas Le Pas de L’Aigle Rouge 2012 – The following vertical hails from the Amadieu’s highest vineyard, the Eagle’s Pass, a transversal rift in the Dentelles which is home to a couple of nesting pairs of eagles. The ’12 is jammy and shows the vintage’s heat, deep with fig and prune. It has a wild nose, sweet fruit, high alcohol but coupled with elegant black and red fruit, it finishes powerfully and warm. $40 Drink/Keep 3-5 yrs![]()

Gigondas Le Pas de L’Aigle Rouge 2010 – Hailing from a great Rhône vintage, this expression of Pas de L’Aigle will outlast the others, declares Henri-Claude. It certainly has the structure to go the distance, displaying tight tannins and marvellous acidity around a core of red and black fruits and spice. It is complex and long on the finish and the perfect example of the Gigondas iron fist in a velvet glove. Not priced Keep 8-10 yrs![]()

Gigondas Le Pas de L’Aigle Rouge 2009 – Gigondas can age, and the ’09 is gracefully ambling down this path towards a delicate savouriness. There is a touch of volatile acidity here, followed by olive tapenade. The body still retains its powerful alcohol but you’d barely notice it, so taken with it’s tea leaf, strawberry confit personality will you be. Not priced. Drink up.![]()

Christopher Wilton lives in Peterborough and is a wine sales representative for the Small Winemakers Collection, a wine educator at Durham College, a server, and the regional liaison on the CAPS board of directors. He is certified with CMS, is almost finished his WSET Diploma, and has his CSW.

Christopher Wilton lives in Peterborough and is a wine sales representative for the Small Winemakers Collection, a wine educator at Durham College, a server, and the regional liaison on the CAPS board of directors. He is certified with CMS, is almost finished his WSET Diploma, and has his CSW.

Yes! Best (first?) reference to Asterix in all of GFR history! Great piece about some delicious wines.

Thanks Malcolm! Did I do the tasting justice? 😉