I have to make mulled wine every year, it’s something I feel truly romantic about, but I never seem to make it the same way twice. With mulled wine recipes dating as far back as 20 CE Rome, there are hundreds of variations for the seasonal favourite from all over the world. It seems every recipe says to do something different, so I took it upon myself to apply considerably more effort than necessary to find the best method for making mulled wine. I conducted over 16 tests with 10 different bottles of wine, over the course of several days.

Fear not, I’ve condensed all my research and testing, so as little time as possible stands between this article and your own batch.

1. How oxidized can your wine be?

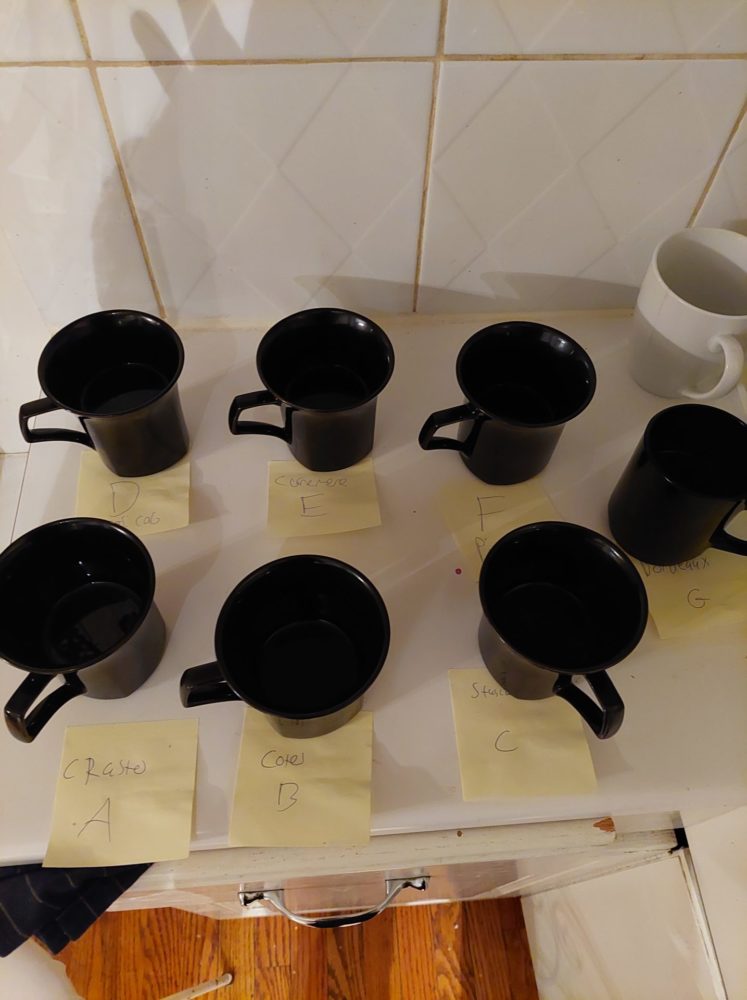

In the past, I used to use any old bottles sitting in the back of my fridge when it came time to mull something red. This time, I tested 7 wines opened 1 week apart (I’d already had them from a wine course I was taking), ranging from nearly two months old, to brand new bottles. The oldest, which had horrible faulted aromas, were improved by mulling (5 minutes at a simmer was the standard for most tests) to the point of being tolerable, but with some unpleasant qualities persisting.

I’d use wines over 4 weeks old for cooking, or at least boil the wine, and then combine with fresher wine when mulling (this is the original technique for ancient roman spiced wine, aka “Conditum Paradoxum”).

Wines 4-2 weeks old became flat and lifeless when mulled, but were also totally inoffensive. The end result was a very flat tasting mulled wine with no character, and little-to-no faulted aromas, so feel free to use that bottle at the back of your fridge. However, the fresher wines (<1.5weeks old) won out in every case when tasted blind, and actually still retained some of their character.

2. Which kind of wine works best?

Mulling removes a lot of subtle character in the wine by boiling away its volatile compounds. Even wines with very powerful and quirky aromas, for example, the telltale green pepper notes that explode from a Chilean Carménère, were almost completely undetectable after mulling.

The most important thing are the primal components which persist after heating; acidity, bitterness, sweetness, tannin, salinity, and body. Therefore I suggest selecting a wine with medium to low tannins, medium to high acidity, medium to full body, and preferably one without any bitter or mineral qualities.

Finally, I try to go for something with high alcohol, as the mulling process will cook some off. Because of this, my darling wine was Grenache, from Southern France or Spain (where it goes by Garnacha). There are a lot of wines that float around the $10 range which hit all of the markers I listed above. Feel free to experiment, but adhere to the above rules and don’t buy an expensive bottle.

Highly standardized tasting equipment was applied for all tests.

3. How to treat spices and citrus

Whole spices won out every time versus powdered spices, in flavour and in ease of filtering out, with only allspice and black pepper having to be cracked to infuse properly. Additionally, lightly toasted spices had a more complex and pleasing effect on the wine than untoasted spices.

For citrus, I also tested searing my ginger and orange slices in a hot pan. The orange slices present a nice and unique aroma when very briefly seared, but the ginger lost some of its freshness and potency in the final wine. However when searing the oranges heavily, they lose a great deal of freshness in the final wine. I also tested roasting the whole oranges, which makes your house smell great, but requires a lot of time and adds little improvement.

Something I fully support but opted not to include, is the addition of dried fruit, in which I suggest you go buck-wild at your hearts desire, dried cherries being a personal favourite.

4. Temperature

Finally I tested several temperature variations, such as boiling the wine, gently simmering, and allowing the spices to soak cold and warming after.

A long cold soak (10-60 minutes) in the style of an ancient Hippocras, improved the infusion of citrus, but missed some amount of spice. Applying heat pulled more from the spices, but either too much or too long reduced and concentrated the wine unpleasantly. In the end, I settled for a combined method, with a short simmer followed by a soak.

5. Fortification

Yes.

That is my full entry for this section. Yes. The body, complexity, punch, and impact of port or brandy in your mulled wine is irreplaceable. A bottle of port will drink well for a while, and is indispensable in cooking rich opulent dark sauces, and brandy will live tenfold on your bar. There is no excuse to make mulled wine without brandy or port.

6. Sugar

Sweetening seems simple, but after a few tests I made some interesting discoveries. I tried honey, agave, maple syrup, and a few different kinds of granular sugar, and it taught me that less is more. Theres a great deal of sweetness from the amount of port that I use, and adding honey or maple syrup was just over-complicating the flavour profile I already had.

Demerara sugar was my eventual favourite, adding just enough richness and backbone, without jumping forward and covering up all our carefully selected spices.

The pieces of the puzzle are finally on the table. All that’s left is to put the theory into practice.

I’ve put together my personal favourite recipe below, but you should be able to apply everything above into just about any recipe out there.

Rob’s Mulled Wine:

This recipe is only for a single cup of wine (about two glasses), scale up the spices by 1/2 for each additional cup of wine, except for the sugar which you should scale up 1:1. If you want to just send in a full bottle of wine and port, just scale everything x6.

- ½ cup of red wine, Grenache or similar preferred

- ½ cup of ruby port, I used Kopke Fine Ruby Port

- 1 large cinnamon stick

- 2 Cardamom pods, gently crushed until split

- 2 cloves

- 1 whole star anise

- 1 black peppercorn, very gently crushed

- A small chunk of ginger, about the size of a pinky finger, sliced thinly

- Two round orange slices

- ¾ tbsp raw sugar

- A thumbnail sized slice of whole nutmeg

Apply medium heat to a saucepan, and add all spices EXCEPT cardamom. Toast until very fragrant, about 1-2 minutes.

Turn the heat to minimum, and add your orange slices to the bottom of the saucepan, searing one side on the residual heat for 1 minute.

Add your wine, port first (the heat of the saucepan will evaporate some excessive alcohol), and then the portion of dry wine, ginger, cardamom, and raw sugar.

On low heat, bring to wine to a gentle simmer, for 5 minutes. Then drop your heat to absolute minimum, and leave for 10 more minutes.

At this point, it can be consumed right away, or you can allow the wine to cool and soak with the spices for up to 1 hour.

Pour into vessels through a fine mesh strainer. Drink.

Absolutely use whatever spices and sweeteners you want, though I learned something interesting creating this recipe about complimentary flavours. At first, I tried using warm and earthy spices, but they simply blended in with the rich spice and dark fruit notes of the port and Garnacha I used.

So instead I flipped the recipe on its head, and switched bright, zesty spices that would pop against the background. It’s a solid lesson that pairing flavours is a case by case basis, and sticking to simple rules such as like with like, can limit your imagination, and your results.

Usually Ill just pour right into my favourite coffee mug, but this looked better for the picture.

I must say, by the 3rd day in a row of making batches of mulled wine for 2-3 hours at a time, I was starting to get a bit sick of the stuff, but I wouldn’t have done if I didn’t truly love it. It’s always been a tradition for me to pester my friends endlessly to come tobogganing with me after every big snow, accompanied by a big thermos of mulled wine. It’s one of those smells that instantly adheres itself to memories and moods. I think if I failed to make mulled wine one year, something irreplaceable inside me would be lost.

I hope you can make some memories with your mulled wine as well.