Tagines, by Santi LLobet via Flickr (CC BY 2.0)

Tajine Cuisine: the Maghreb’s One Pot Wonder

One-pot stews and slow cooking recipes are popular for the convenience offered. You get a hearty, nutritious and tasty medley to fill the belly. In summertime, having one element on low or medium with a light seafood stew works beautifully over blasting multiple elements, roiling and boiling. In the winter, simmering complex layers of spices to saturate meat and root vegetables brings warmth to the hearth.

A slow-cooker in modern parlance usually means something you plug in and turn on while you go about the rest of your business. But the idea predates the electrical outlet by at least a thousand years, possibly two thousand. The original is called “tajine” (or tagine), a word that describes both the pot and its resulting repertoire of stews.

“Tajine” is understood today as Moroccan, but tajine cuisine is a Berber tradition. Berbers live in Morocco, but also throughout the Maghreb, or North Africa. Berbers are the Indigenous people of North Africa, and they were historically nomadic, living then and now in Morocco, Algeria, Libya and Tunisia.

The Berber word “tajine” means “shallow earthen pot.” It was a two piece clay vessel. The lower half was wide and round with low edges. The top piece was a tall cone with or without a hole at its peak.

Woman with Tagine, Algeria, 17th century

Tajine cookery is ancient. The oldest origin we know of is continuously moved back into time. It was mentioned in One Thousand and One Nights, the collection of Arabic folktales and stories in the 800s. But archeologists have identified tagine fragments in today’s Tunisia from the Numidians. Numidia was an ancient kingdom in North Africa, from 202 to 45 BCE. They were Berber people.

The tajine is a one pot wonder designed for cooking over an open fire. The unique conical construction of the tajine means that rising moisture continually drips back into the pot, being reabsorbed by the clay itself as well as the ingredients, and the reason for the remarkably juicy stews that result. Tajines with a hole in their summit are a matter of preference and sometimes arguments between cooks and families. Both are very moist modes of preparation. Tajines with a hole allow more moisture to evaporate than those without, making the sauces more concentrated.

Tagines, by Pascale Van de Wouwer via Flickr (CC BY-ND 2.0)

Either way, the tajine was an ingenious solution for nomadic kitchens because meats of the region could sometimes be dry and chewy. Lamb was wonderfully succulent, but camel is typically on the tough side. Older animals especially have a wizened texture. On the other hand, desert cultures often had limited access to water. We take for granted simply turning on the tap. Water for cooking was a luxury, so the tajine helped limit how much liquid was necessary to make soups and sauces. The tajine made moist, melt-in-your-mouth magic out of all kinds of meats and roots while conserving the available liquids.

The conical pot top makes the tajine a remarkably effective piece of engineering. But clay or earthenware pot cooking itself is an ancient solution. Terracotta or clay cooking is traditional to many cultures, and offers amazing benefits. Clay allows heat and steam to circulate evenly. This has a natural tenderizing effect on the food. Clays also offer additional nutrients from the local earth, such as iron, phosphorous, and magnesium.

We were throwing big fish and game onto the fire for some time, and somewhere around 20 thousand years ago we figured out that using a vessel to contain fluid or vegetables could help make plants more edible. Sure, berries were nice on their own, but ever try eating a raw tuber? Different cultures had different local clays and very old vessels have been found in many parts of the world. Some of the oldest clay pot pieces have been unearthed in China. Clay pots around four to five thousand years old or more have been excavated from Mesopotamia, Egypt, and the Indus Valley. Clay pot cookery was common and widespread everywhere by 500 BC and remained the norm until the 20th century with the spread of industrialization, electrical devices, and commercial cookware.

Tajines are made in different sizes and styles, and come as plain, unglazed clay as well as in a wide variety of decorative patterns. The ornamental beauty of the ones painted with brightly coloured tastir, or geometrical patterns, is sublime, but many if not most of these should not be used for cooking! They can be stylish additions to a kitchen to be used as fruit bowls or as a sculpture. Even those sold for cooking purposes may not be safe or suitable depending on the pigments used. There are many tajines that are painted with natural pigments in a limited palette that are meant for cooking, and some are engraved as well. Generally speaking, those painted in earthy colours are more likely to be intended for use over the fire or stove rather than as decorative only.

La Maison Arabe Cooking Class, by The Travelista via Flickr (CC BY 2.0)

Some western companies make tajines as well and they come in different colours or patterns. My preference is always for an artefact from its source of origin, however. The humble, unglazed, earth coloured clay tajine made in North Africa will bring great satisfaction to any kitchen. You will easily bring many delicious meals to life.

An important factor in choosing an unglazed tajine is the earthy flavour it imparts into each dish. Additionally, the spices and flavours from every meal become part of the pot, and add a distinctive flavour to every meal cooked in the tajine after. Each clan or family or cook has an undefinable flavour profile or essence that comes from their own pot.

You’ll want to learn a bit about the care and feeding of your tajine. Tajines are made of the earth, and they can and do crack fairly easily. There are soaking and preparation techniques that help prevent or delay this reality. (They are easily biodegradable, which is a bonus.) The tajine should not sit directly on the fire, BBQ, or stovetop element. You’ll need some kind of diffuser or buffer.

The purpose of a Berber meal in general, and the tajine in particular, is to bring family, friends, neighbours, visitors, and strangers together. Generous hospitality and long shared meals are cherished customs of the Middle Eastern, Arabic, and North African cultures. Tajine cooking can take several hours, affording families time for relaxation and refreshment, while inhaling the spicy aromas. The tajine is both the vessel for cooking and the serving dish. Traditionally, diners take bread and use it to scoop the stew from the communal pot.

Fish Tagine, by Edsel Little via Flickr (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Tajine is not one specific kind of stew. Anything cooked in the tajine is tajine. There is no typical single tajine recipe. However, it was customary to layer a large array of flavours and ingredients together. Salty choices like fat green olives or pickled lemons are common. Fruits are widely used as well, including dates, apricots, and cherries. An array of meats and vegetables are possible, in any combination. Spices include paprika, cumin, cardamom, ginger, and saffron.

All tajine recipes can be made easily in any other kind of stovetop pot, other kinds of clay pots, or slow cookers. You can use tajine recipes to deliver endless ideas for memorable one pot meals by any means of preference. But it is well worth investing in a tajine and learning how to prepare the pot and care for it. It isn’t difficult to do and comes with tender, aromatic rewards. (The author recommends the online Casablanca Market tajine. It is large, unglazed, and classic, and first time shoppers get a nice 15% discount, with reasonable shipping fees.)

Getting a cookbook with your tajine is also worth it. You will learn more about tajines and how to get the most from yours, and you’ll have enough inspiration to grow confident. Tajine cuisine is simple to learn, and the results are rich, delicious, and nourishing.

Here are a few ideas to get you started. Any printed recipe will specify a quantity, such as a teaspoon, cup, or pound. Most people who cook tajine don’t use measurements. If you prefer intuitive cooking to stringently measured baking, you’ll be in heaven. If you rely on the precision of instructions, make use of them until you have played around with flavour layers and feel confident about your instincts. Either way, you can’t go wrong.

Chicken. Lemon and Olive Tagine, by BBouchra00, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Moroccan chicken with lemon and olives is a widely loved tajine. You’ll find an infinity of variations in cookbooks and online and in recipe files of anyone with family in North Africa. This tajine combines chicken (traditionally a whole chicken), green olives, and preserved lemons, as well as spices like garlic, pepper, turmeric, ginger, onion, parsley, and cilantro. The trilogy of chicken, olives, and pickled lemons stars inside a rich medley of tastes. It is salty and sensational, meant to be scooped up by chunks of bread.

Not everyone is accustomed to cooking with preserved lemons. You can make your own easily or buy them in Moroccan food stores, or even on Amazon for an arm and a leg. If this classic tajine is intimidating because of the preserved lemons, just go for lemon slices and salt. It will still taste amazing and you’ll want to try it again.

Another Maghreb regional classic tajine is kefta mkaouara, or Moroccan meatballs. Mince green peppers, onion, chile, cumin, cinnamon, paprika, and salt with ground beef or lamb or both, and use eggs to glue the mixture into meatballs. Simmer them in a stew of crushed tomatoes, olive oil, parsley, garlic, and bay leaves.

The “everything tajine” is something many households swear by to make use of all the bits and pieces left in the fridge and freezer. Combining ingredients into a full meal works like magic with a tajine! If there is just one sausage and a lonely frozen chicken leg, or some seafood that you need to stretch out, throw everything together to bubble and blend in a tajine. Salvage what you can from bunches of parsley and cilantro. Save those softening tomatoes and peppers. Add dashes of salt, pepper, ginger, chile peppers, saffron, paprika, garlic, turmeric, cumin, you name it. Classic Maghreb tajines also stew fruits and nuts so there is literally nothing you can’t add to the everything tajine.

Lorette C. Luzajic

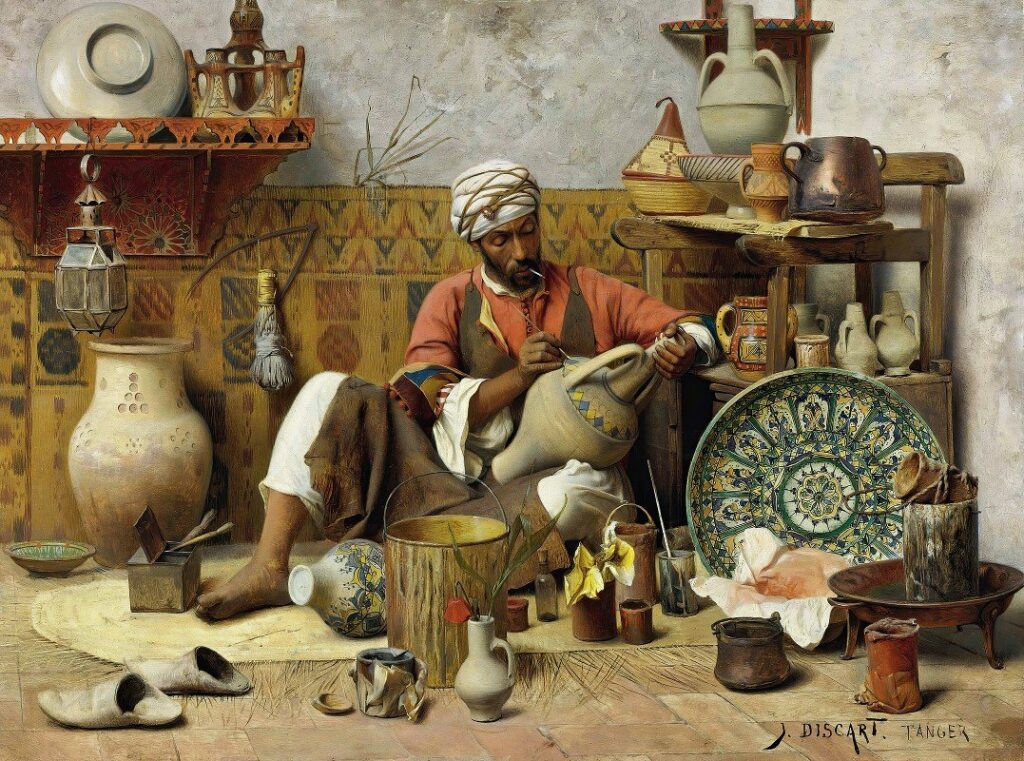

Pottery Workshop, Tanger, oil painting by Jean Discart (France, b. Italy) c. early 1900s