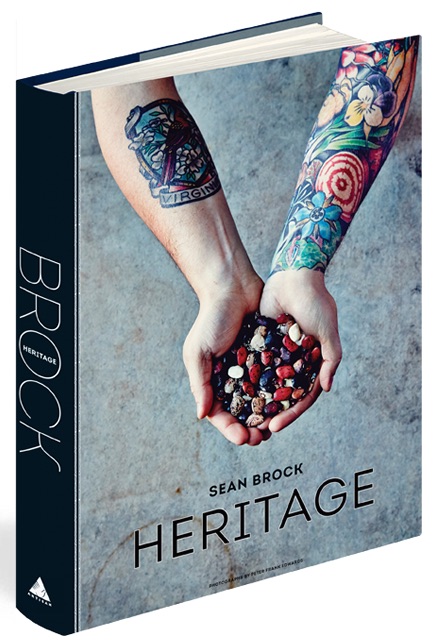

Chef Sean Brock was in Toronto recently to promote his new cookbook, Heritage, answer questions at a public appearance with Alison Fryer, and search out the city’s best Chinese food. Brock is a successful restaurateur based in Charleston, South Carolina where he overseas the kitchens of Husk, McCrady’s and Minero, as well as an outpost of Husk in Nashville. Brock was the subject of a season of Anthony Bourdain’s PBS television program Mind of a Chef, he’s a James Beard Award winner and part of the bleeding edge fellowship of chefs that congregate around René Redzepi’s Mad Food Symposium. In other words, he’s a big deal in the gastronomic world. He’s also a soft-spoken Southern gentleman, with a deep respect for the food and culture of his adopted home in th eLow Country. Heritage, which is (surprisingly, given his renown) his first, is document to that. It’s a collection of recipes (including one for a whole pig, which lists cinder blocks as an ingredient), but also a collection of stories and insight into the story of a man who learned to cook from his grandmother and pushes gastronomy forward by keeping a keen eye on the past.

I met Brock to conduct the interview below, which has been edited for clarity and style.

INTERVIEW

Good Food Revolution: I was surprised that Heritage is your first book. I guess I just assumed that you would have had a few more with all your restaurants and things.

Sean Brock: Well, it should have come out in 2011, and I should have written many more since then, but it didn’t work out that way. It became this crazy project that went from being a book about the Low Country to sort of a personal diary and documentary of my entire journey as a chef: all the things I discovered, remembered, learn and realized. So, it turned into a monster. [Laughs.]

GFR: From my perch in Toronto, which is far enough away from the Carolinas, it seemed a bit like you just burst on the scene a few years ago, but in fact you’ve been cooking since you were 15 years old and yours has been a long journey.

SB: I have been cooking professionally for 20 years. I love telling young cooks that when they say, ‘I want to do what you’re doing’. I ask how long they’ve been cooking. You know, it doesn’t just happen overnight. And it’s not supposed to be that way. This took 20 years. And if you look at the food I was cooking at 25, on my first chef job, there were similarities with what I’m cooking now, but there’s that beautiful thing about wisdom that comes from making mistakes, and meeting people. You start to realize what you’re put here for, you know? That becomes your inspiration.

GFR: So, is Heritage about a person? Or a place?

SB: The book is about an idea. It’s about exploring either your roots, or heritage, or one that you can relate to and makes you very, very happy. You know it’s interesting: if you really read through the entire book, you’ll see that it’s all over the place. There’s a lot of Appalachian cooking. There’s a lot about Low Country cooking. There’s a lot about modern cooking. And there’s a lot about family recipes. There’s a lot about restaurant cooking. A lot about cooking at home. But I did that because this is everything that goes through my head on any given day. It’s everything that I’ve experienced over the last 20 years cooking, and all those things make me very, very happy and I’m lucky because I have gotten to experience all of them. The idea that searching, or trying to understand your heritage or your roots is something that not only helped me be a better human being, but a better cook. I am a cook that cooks with more purpose and the idea is to help people take that same journey. It doesn’t have to be about the South and it doesn’t have to be about your grandmother’s food. I have met a lot of people whose grandmothers were terrible cooks…[laughs]. It’s more about finding a cuisine that speaks to you, and in some form or fashion makes you really happy.

GFR: In your Manifesto [published in the book], that’s one of the things. That you have to enjoy cooking, and its a problem if you don’t.

SB: Yeah, if you’re not having fun, then something’s wrong! When I get that way I go out to dinner – that’s why I have restaurants.

GFR: Right! Now, you only provision from south of the Mason-Dixon Line. How did that come about?

SB: Well, it goes back to my grandmother. I really saw a major difference in the flavour of food when I started cooking in a professional kitchen. I remember some of my first tasks handling food in a restaurant, something I had been dying to do since I was 10 years old. It was a big let down because the beans didn’t taste very good, the squash didn’t taste very good, the lettuce didn’t taste very good. It was all kind of like the same; it didn’t have any character. It was very confusing. Then, I realized my family had been growing the same plant varietals for several generations for a reason: they’re more delicious. All those seeds on the cover [of Heritage] are perfect example. Each one of those seeds carries a very particular flavour and story. The story is about a place, a person a period of time. And if those things aren’t being grown, eaten and celebrated, then those tastes kind of fade away. And that starts to affect a culture. Ultimately I am obsessed with culture more than anything; the idea of the various art forms, being influenced by them, and influencing them is something I really enjoy. I believe that what makes up a cuisine is somewhat of a formula: there are plants and foods that belong in a certain area because they thrive in that climate. That’s why they’re there in the first place. Then, obviously, the cultural influences might bring in various foods to a region, where they may not have existed before. Those cultural influences will cause an adaptation of those ingredients. To me that’s how cuisines are formed, and if you can keep that in mind, then you can move a cuisine forward in the same spirit.

There are certain foods that belong in a certain place that make you feel a certain way when you’re sitting in that place. Southern food, luckily, is full of these tiny micro-regions that have these different cuisines, and dialects and accents, and types of music, and various types of folk art. That diversity is what makes the South so special. Celebrating that and trying to understand it is why I was put here.

GFR: But how come? Why is this particular part of North America blessed with these very distinct foodways?

SB: The South? Well, if you look at it as far as the United States is concerned, it’s one of the older parts, where people first started settling. So, we have a deeper history. And if you look even past first contact and European settlement, you’ll see that the South was really the hub of agriculture that fed the East Coast. So, that agricultural history brings a different type of cooking, a more deeply rooted style of cooking. The Low Country is a great example that I write about in the book of how one plant, rice, accidentally came in the 17th Century. It wasn’t supposed be there, it wasn’t planned, but it was planted and it grew like crazy. And it helped build that region. In the people who worked the fields, including Native Americans, the Italian planters and the West Africans, and the English, you see a special cuisine come out of that area. And that’s pretty fascinating and delicious.

GFR: That’s Carolina gold rice, with which you are now very much associated. How did you get involved with its resurgence?

SB: I never thought I’d be ‘the rice guy’, by the way. It’s all Glenn Roberts [of Anson Mills] fault. I started buying food from him when I was cooking in Virginia. He was growing corn for grits and cornmeal. I remember ordering from him and speaking with him on the phone. I never heard anyone speak about food like that. I never heard anybody get so excited about a freaking kernel of corn. I was like, ‘who the Hell is this guy? What’s wrong with him?’ But we became very good friends and I had been previously cooking in Charleston and had gone to culinary school there, so I had a great interest in its culture and cuisine. When I got back to Charleston in 2006 as a cook, he had been working for years on restoring the pantry of what we refer to as the Carolina rice kitchen. What’s interesting about that, and why that work is important, is if you look at trying to bring rice back, you can’t just bring rice back. You can’t just keep planting rice because the rice borers take over and the crop fails. You have to plant several plants before and after the rice to enriched the soil and keep it healthy and free of disease and pests. You need a proper crop rotation, and all this plants that are part of the crop rotation end up making up the pantry, and forming the menu. So, he’d been building up the pantry with things like beniseeds, and sea island rice peas, and sea island red peas, and okra, and sorghum, and green peanuts, and farrow. All these foods add things to the soil, or balance the soil, so you can grow the rice. That’s what’s fascinating. It all comes from one crop: its existence and survival can write a menu and create a cuisine.

I have been lucky enough to taste all of those things along the way. Every single one that I’ve eaten has been extraordinary. And it’s made my cooking much simpler because I know have the core and the foundation and the flavour that I didn’t have before. Every chef knows the more beautiful a thing is the more delicious it is and the less you have to mess with it. That’s been my journey and it started with rice.

Chef Sean Brock’s cookbook Heritage is available widely, including expertly curated independent stores like Good Egg in Kensington Market and The Cookbook Store Corner at All The Best Fine Foods in Summerhill.

Malcolm Jolley is a founding editor of Good Food Revolution and Executive Director of Good Food Media, the company that publishes it. Follow him on Twitter or Facebook.

Malcolm Jolley is a founding editor of Good Food Revolution and Executive Director of Good Food Media, the company that publishes it. Follow him on Twitter or Facebook.