Rachel Roddy has published a very personal book of Roman food.

Rachel Roddy landed in Rome more than a decade ago with no intention of staying. But when a friend suggested they explore the old meat processing neighbourhood of Testaccio, something clicked and since the English woman is settled in the Eternal City with a young son and Sicilian partner. Roddy writes about her culinary life in Rome at her blog Rachel Eats, and at her Kitchen Sink Tales column for the Guardian newspaper.

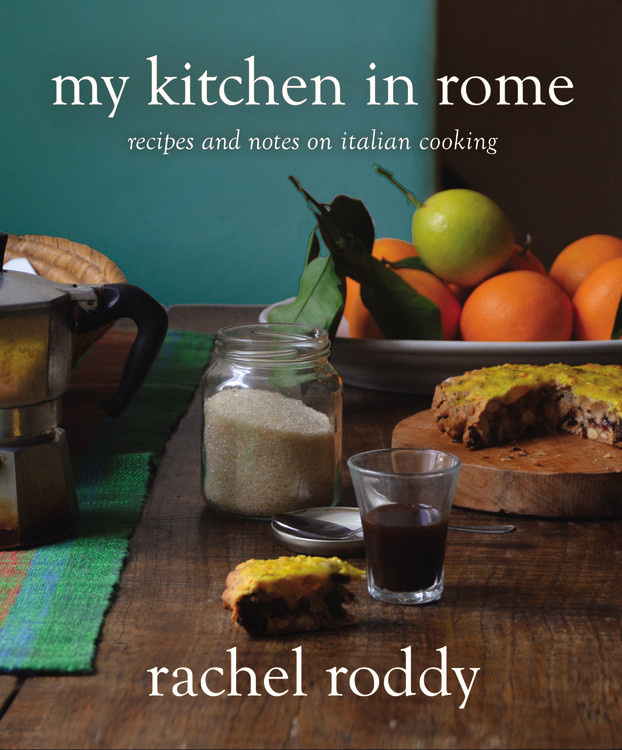

Last year Roddy published her first cookbook and memoir about her life in Testaccio. Five Quarters recently won the prestigious André Simon Food Book Award for 2015. This week the North American edition of the book was launched with a different title, My Kitchen In Rome.

My Kitchen In Rome is a beautifully written and shot meditation on Roman cooking. It’s also a book written by a Londoner with a keen appreciation for the best British cookery writing. So, the preamble to what might seem like a quintessentially Roman dish might also allude to recipes by Jane Grigson, or maybe Fergus Henderson. This has the effect, at least for this literary foodie, of creating rapport and familiar context for her recipes, without in any way dumbing them down. My Kitchen In Rome belongs on the thinking person’s cookbook shelf.

The recipes in My Kitchen In Rome are organized by the traditional progression of an Italian meal. First antipasti: fired morsels of vegetables, cheeses and cured meats, bruschetta and so on. Then soup or pasta: the bean thickened minestre and vegetable laden minestrone or the classic Roman paste, including a twist on cacio e pepe that uses ricotta. Then a dish of meat in all manner from the colossal porchetta to the modest Roman tripe. Surrounding the meat, of course, comes the contorni, the vegetables in season (Roddy told me the artichokes were now appearing in Roman markets) from asparagus to zucchini. Finally dolci with a firm emphasis on fruit.

I spoke to Roddy in her Roman apartment via Skype this week for the interview below.

This interview has been edited and shortened for clarity and style.

Good Food Revolution: This book in front of me, My Roman Kitchen, has another title in the UK, Five Quarters. What’s that?

Rachel Roddy: So, you have the American edition? Well, there were five reasons for five quarters. One of them is the “quinta quarto”, the fifth quarter, which is the offal from an animal. It makes up a quarter of the weight: tails, tripe, liver, balls, all of that. And the cooking that takes quinta quarto as its name was born literally a minute away from where I am sitting in Testaccio. And this part of Rome is shaped like a quarter, it looks like a piece of cheese. And Roman cooking is very resourceful in general, not just with offal but following this idea of using what would otherwise be thrown away, whether it be pasta cooking water, or broth, or ricotta which is made from he waste product of cheese making. And the most important quarter, as I see it, is the kind of non-existent ingredient, the cook. Roman food is relatively simple home cooking and it’s all about the cook making the recipe their own. Some of the recipes [in My Kitchen In Rome] are almost stupidly simple. Well, of course, traditional cooking is, isn’t it? It’s dependent on good ingredients, and then the cook. Whenever I am given a recipe in Italy the advice that comes with it is always “practice”. It’s as if to say, go and make this carbonara recipe ten times because then it will become your own.

GFR: I like the orginal title, and the book has done very well in the UK, even just won a big award. Why did they change it for our side of the Atlantic?

RR: I think they were worried that people would think it was all about offal, which it’s not. But I’m very happy for the new edition. Although it is creating some confusion, especially since I’ve had some publicity recently in the UK for winning the André Simon award. People say to me, wow you’re amazing you’ve written another book! [Laughs.] They’re very impressed until I have to explain that I haven’t.

GFR: I am not surprised there’s a lot of interest in In My Roman Kitchen, and I bet you’ll find an eager audience in North America, in part because if you fly directly to Italy from here you’re most likely to fly to Rome and spend some time there. Rome is the transatlantic gateway to Italy. And when I’m there, there seems to be a real pride in the city’s particular cuisine. There are signs on the restaurants advertising ‘authentic Roman cuisine’. Is that what drew you to live there?

RR: No. I came ten years ago, but I didn’t want to stay in Rome. I was quite reluctant. I liked to eat well, and I liked to write but I really knew nothing about Roman food. It was only when I came to Testaccio, in the old slaughterhouse district, and rented a little flat above the old market that I became interested. What it literally was – and this is what got me writing – was that I was living by a bread shop and a really traditional trattoria and the atmospherical market, which seemed medieval with iron work and glass ceiling that was always dirty so the light inside seemed like a Caravaggio painting. It just kind of tripped me up. It was so visceral: every morning I was woken up by the smell of bread. I don’t want to over romanticize it. The trattoria was forever boiling greens and broccoli that just reminded me of school. But the other smells of pancetta frying, and roasting peppers… The door to my flat opened into an internal courtyard which was like a vortex of smells from the bakery and the trattoria, and all the pots of coffee in the building, and people boiling chickpeas on a Tuesday. I just kind of joined in. First there were the smells, then I wanted to taste them, then I wanted to cook them. I can be quite matter of fact, but it was such a sensual experience for me. And, that’s when I started writing. I thought I’ve got to write this down.

GFR: With help? I mean the cooking: who helped you with the cooking?

RR: I started cooking with my neighbours, and I also met a Sicilian, whose been in Rome for a very long time. I made him promise we would go live in Sicily (which we will one day), but now we have a little boy, and Testaccio is where he’s from.

GFR: Rome and Sicily are two of my very favourite places so when you write your Sicilian cookbook I’ll be the fist to buy it! But, back to My Kitchen In Rome. I try and read through a cookbook before I interview its author, and that’s usually not a big time commitment, at least to get a decent feel of the recipes and writer’s point of view. I am not at all close to finishing your book because there is a lot of writing. Of course, you don’t need to read the essays in the book to follow the recipes, but I certainly want to, especially all the stories about the people in your neighbourhood, your suppliers: butchers, bakers and that kind of thing. You are clearly very well integrated into your community, but as an immigrant how long did it take to fit in?

RR: Probably a few years. But with Italians, if you go somewhere twice, if you return somewhere regularly, you’ll begin a relationship. It’s very villagy, Testaccio. Of course, while I wasn’t a young, young woman when I came to Italy – I was 32 – I was still relatively young and I think that helped. I was also quite loyal to places and kept returing to them. So, within a few years I had good relationships with the people in my shops and the market. And then big changes came when Luca was born (he’s four years and four months): people saw me pregnant, and Italians make a great big fuss about pregnant women, and then there was this little boy in a sling and then running beside me. He’s grown up in the places I write about in the book. He’s probably been to our bar every day of his life. He owns it in a way that I never will. So, I’ve been here a long time now, over ten years, but I fit in very quickly. Loyalty is really repaid in Italy, especially around food shopping.

GFR: It sounds really charming.

RR: I’ve just come back from London, where my family is, and it’s so different from here. In Rome there are still lots of little shops and people still shop every day, or sometimes twice a day. Although things are changing here. Food traditions in Italy are changing at a scary speed, and I am reminded not to idealize. But yeah, it still incredibly traditional the way people shop, and I go to the market absolutely every morning and I meet the same people there buying oranges. And people still buy bread once a day. Even if people work, the bread shops are open until late at night and they still sell bread in little pieces so you can buy only as much bread as you need. My neighbour used to buy one slice. It’s very old fashioned. It reminds me so much of Northern England when I was a very little girl and I would see my grandparents. It’s that very small villagy; it’s nosy, everyone knows everyone’s business. [Laughs.]

GFR: Ah, great segue way, as I wanted to ask you about the parallels you make between some Roman dishes and traditional English ones. You make a lot of connections.

RR: Yeah, I suppose food is all about making connections, isn’t it? But yes. There’s the offal, of course. And the resourcefulness. I suppose it’s like any really popular cooking, or traditional good home cooking that depended on basic ingredients like lesser cuts of meat, beans, greens and root vegetables. I could probably have found those connection in any other food culture, couldn’t have I? But Roman cooking does remind me of English cooking. Northern English cooking has a huge tradition of offal cooking, and the Roman sstill eat a lot of offal, particularly tripe, liver and tongue. That’s really, really Northern. My grandparents were from Yorkshire and Manchester. My grandma Roddy (who wasn’t a great cook – my other one was) would always boil a tongue, which is what they do here. And geographically the Romans have this volcanic soil, so they grow peas, leeks, the brassicas and greens that we have in England. And then there are some little things like the love of cream as in panna cotta. Or, the Romans also have all these lovely, dense fruitcakes. One of my favourite recipes in the book is the pan giallo for Christmas. It is, in fact, the picture on the front cover. It looks like such a weird thing. It’s basically a ball of dried fruit and nuts bound by honey. It’s delicious, especially if you use nice figs and nuts, and it’s just like an English Christmas cake. So, it was very nice to find those connections. Also, as a cook I had kind of lost my way in the UK. I was a fancy cook, whereas my grandmothers were incredibly careful and resourceful cooks who made very simple food that used up leftovers and had this great sense of one meal rolling into the next, particularly my Granny Jones. The meat would make a broth that would make a soup. The bread would make a bread pudding. It’s this lovely ‘roll’ in the kitchen, that I find so interesting as a food writer, and that I found here. I feel like I am pulling all those things together.

GFR: And it’s delicious food.

RR: I am writing for a newspaper, The Guardian, and I’m really excited about it because in a world full of fancy recipes they’re letting me talk about these nice, simple and maybe seemingly a bit boring, really, recipes. But nice everyday practical tasty food.

GFR: But I think that’s how people who do actually cook every day cook. The recipes in the book, or what you do in the Guardian is what people make to feed themselves or their families.

RR: I think it is. But, you know, I didn’t used to. I think I had forgotten a lot of these skills. I was so recipe driven. That was one of the things we wanted to do with the book: get away from that. Yes, it’s recipes, but I never have a problem if people want to go and look at another recipe book as well. It’s more about ideas about how to eat, really. A lot of these things you don’t need recipes for. You can get the hang of the minestre, the thick bean soups. (When I first came, I thought the minestra were really odd: I’d ever had bean soups with pasta on them, or pasta and potatoes.) You don’t really need recipes, you need a bit of advice and know how you can vary it and off you go. I really like this idea of freedom from recipes and I’m going to explore it more in the next book.

My Kitchen In Rome is available wherever fine cookbooks are sold, like Good Egg in Kensington Market.

Malcolm Jolley is a founding editor of Good Food Revolution and Executive Director of Good Food Media, the company that publishes it. Follow him on Twitter or Facebook.

Malcolm Jolley is a founding editor of Good Food Revolution and Executive Director of Good Food Media, the company that publishes it. Follow him on Twitter or Facebook.