Still Life with Elephant, oil painting by Jan Mikulka, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Pomegranate: Jewel of Heaven

“No doubt you have forgotten the pomegranate trees in flower,

Oh so red, and such a lot of them.”

D.H. Lawrence

The wine was like claret, plush and deep and shimmering. It was both dry and sweet at the same time, with a faint herbal bouquet and an astringent, cleansing finish. The most unusual quality was how this fuchsia-red was served chilled. I pictured it flowing into a sun-drenched world from a mountain spring.

“What is this…elixir?” I gasped, when I finally came up for air.

I was with friends at Banu on Queen West in Toronto. Banu is a very special restaurant celebrating the cuisine and culture of Iran while promoting freedom and rescuing Iranian refugees from the deadly regime. There was a banquet of splendour, lamb and saffron and mint and lemons and apricots and shallots. But it is the taste of what was in that bottle that still dances on my tongue many years later: pomegranate wine.

Pomegranate Wine, by Ollios, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

The pomegranate is the bright red (and sometimes pink, gold, purple, or almost black) crowned globe fruit of the punica granatum, a deciduous shrub with oblong leaves and red petaled flowers. Tearing or cutting open the sphere reveals a ball of juicy, sweet seeds behind thin membranes of flesh.

Native to ancient Persia, the pomegranate has been a culinary staple and an essential element of symbolism and folklore from Iran to India and throughout Mesopotamia and the Mediterranean for millennia. It was one of the first fruit trees to be domesticated, dating as far back as 5000 BCE.

Pomegranate Tree, by Peyri Herrera via Flickr (CC BY-ND 2.0)

Pomegranate wine is a luscious alternative to grape wine, or a genius blend of the two, a popular homemade ferment or small batch wine throughout the Caucasus, Middle East, and Near East regions. It isn’t commonly offered commercially, with a few options hailing from Georgia, Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Israel available on the market. Unfortunately, wine production is not allowed under sharia law in Iran, so the wine of the Persian fruit of heaven cannot be produced in the fruit’s location of origin.

This stunning love potion is not the only gift of the queen of fruit, of course. Persian cuisine uses a sprinkle of the fruit’s garnets throughout everything. Mutabbal, or baba ganouj, and other sides and sauces are full of them. Fesenjan, a chicken and walnut dish, is just one kind of stew that uses pomegranate molasses for flavour and thickening. And the pomegranate beef tenderloin is one of the stars of the Banu menu, too.

Muttabal/ Baba Ganoush, photo by Stijn Nieuwendijk via Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Everyone adores the bright, sweet-tart flavours of the pomegranate. But westerners are often allergic to inconvenience, and many couldn’t be much bothered with the labour intensiveness of eating them. It is intricate work to unravel the bitter layers of membrane from the little jewels. Cutting them open wasn’t a simple solution, either, for the mess averse. Until recently when peeled, prepared pomegranate seeds started appearing on supermarket shelves, we tended to view them as exotic, special-occasion fruits.

The sad Styrofoam and saran wrap packages, leaking garnet nectar at the seams, were a savvy marketing response to the growing documentation of good news about the heart health benefits and disease fighting properties of this edible medicine. All the anthocyanins and anthoxanthins and antioxidants inside were also mined for juice for smoothies and various other health tonics.

Stamp from Azerbaijan

But even when we seldom ate the pomegranate, everyone knew what it was. The red fruit has profoundly entrenched the human imagination with both passion and divinity. The arts are steeped in lore associating the pomegranate with fertility, femininity, and beauty, and sacred mystery. The word “pomegranate” means “seeded apple” or “apple of Grenada” depending who you ask.

The fruit is nearly universally understood as a womb symbol. The myths of Mesopotamia and the surrounding areas, as well as classical Greek and Roman mythology, are steeped in the connection. Aphrodite, goddess of love, was said to have planted the first pomegranate tree. The fruit was a key symbol is the story of Persephone, representing life and death and the cycles of regeneration.

Yerevan Markets, Armenia, photo by Arthur Chapman via Flickr (CC BY 2.0)

These ancient relics of the goddess are hidden in plain sight everywhere we look. Markets of Armenia have tables overflowing with bright pomegranate ornaments, complete with a slit spilling seeds. (In modern Armenia, it is also a symbol of rebirth and regeneration after the genocide.) Decorative arts of Persia are covered in the fruit. Ancient stone carvings of the pomegranate are found on walls and gates across the lands from Egypt to Iraq to Spain.

Fallen Pomegranate, Armenia photo by Nina Stössinger via Flickr(CC BY-SA 2.0)

Even the pillars of King Solomon’s temple were decorated with hundreds of pomegranate ornaments, according to the book of Kings. “And the chapiters upon the two pillars had pomegranates also above, over against the belly which was by the network: and the pomegranates were two hundred in rows round about upon the other chapiter.” (1 Kings 7: 20)

Even today, the ornamental gold or silver filials adorning the top of the Torah scrolls are shaped like pomegranates, and their name, rimmonim, means the same.

Rimmonim, צורף דרך, CC BY-צורף דרך, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

It’s no secret to these cultures where the symbolism hails from. The pomegranate has been used for that very purpose, in fertility rituals and spells. The religious significance of pomegranates in the Abrahamic faiths, and others, are not necessarily separated from the sensual associations. The life force is sacred on both heaven and earth, after all.

The pomegranate is a central element of the Rosh Hashanah holiday for Jewish cultures, where it symbolizes the new year and new life. Pomegranate lore says the seed count of each fruit is 613, which corresponds to the 613 commandments of the Torah. A familiar Talmudic proverb about God’s commandments says, “Even the empty are filled with mitzvot, like a pomegranate.”

With its abundance of seeds, of course, it also represents fruitfulness.

The lustier interpretation of the symbolism is not lost on the Old Testament writers, either. The Song of Solomon is filled with racy love poetry, ribald enough to make anyone blush.

The classic King James version reads, “Thy plants are an orchard of pomegranates with pleasant fruits; camphire, with spikenard.” Say what? The New Living Translation is a little more clear. “Your thighs shelter a paradise of pomegranates with rare spices— henna with nard.” (Song of Solomon 4:13)

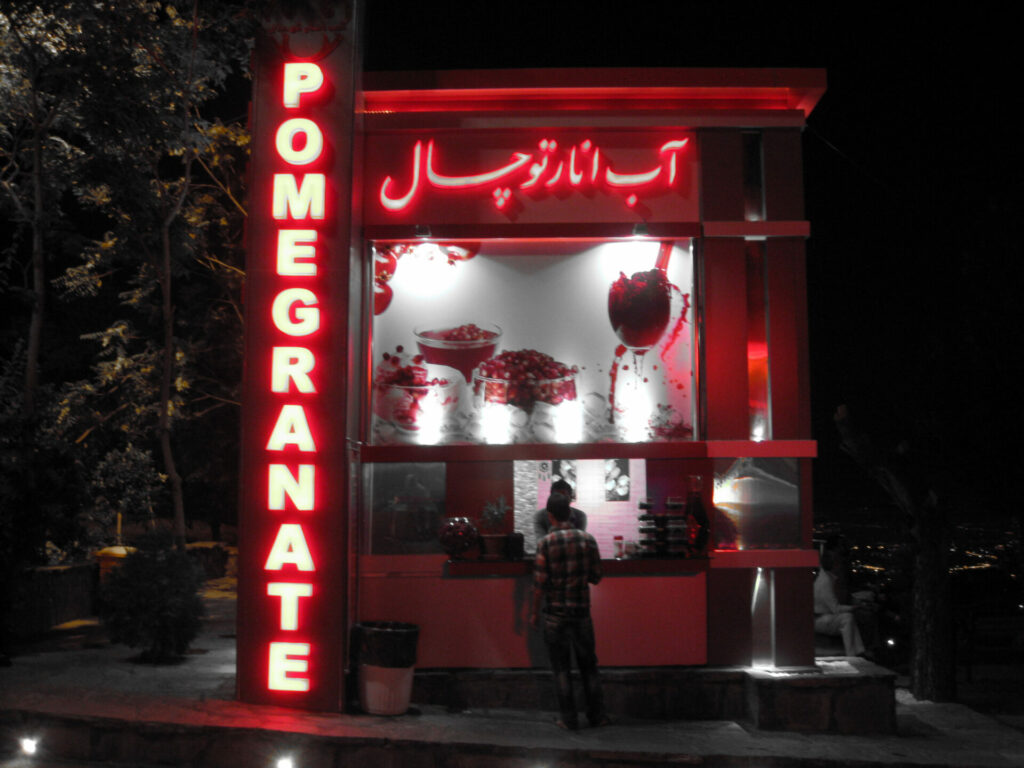

Pomegranate Stand, Tehran, photo by Matthew Carson via Flickr (CC BY-ND 2.0)

In Iran and other cultures nearby, it is a tradition at weddings for the bride to smash a pomegranate on the ground. This scattering the seeds is symbolic of the children she will be blessed with.

Madonna della Melagrana, by Nicola Quirico, CC BY-SA 4.0via Wikimedia Commons

Christian cultures, like Armenia, have similar seed scattering rites, too. But the pomegranate was also commonly used by Christians in medieval times, with many paintings showing Mary holding Jesus, who is holding a pomegranate. Like the pagan myths preceding these depictions, the pomegranate symbolized life, death, and rebirth or resurrection. Nowhere is this shared lineage as apparent as at the Paestum shrine in Italy, home of the Madonna del Granato or Madonna of the Pomegranate. This very place was the temple of Juno, mother of mothers, who sat on her throne with her very own pomegranate before her.

Hera, with pomegranate 4th century BC

All cultures and all religions are syncretic, of course, that is, blending and borrowing from those around and before them. Older or related neighbouring rituals are often layered into ceremonies and holidays. We are sometimes surprised how much of something is from somewhere else, but syncretism is really how everything works. People take their ideas, beliefs, customs, experiences, and arts with them wherever they go, imparting those to everyone they meet and in turn absorbing much from the exchange themselves. It happens through travel, conquest, immigration, emigration, marriage, and business. It can be a conscious decision, the way it was for the Christian church, who understood they had a better chance of longevity if they paired their holidays with the local ones already in place. But it is often unconscious, a natural and organic process.

Madonna of the Pomegranate, Sandro Boticelli (Italy) 1487

Perhaps the best place to observe syncretism is with cuisine. We usually call it fusion when it’s about food. My home city of Toronto is a bounty of mouth-watering melanges. We’ve got Rasta Pasta in Kensington Market, with Jerk Chicken Lasagna. We have Hakka restaurants, spectacularly delicious Indian-Chinese dishes. We even have “photine,” which is Vietnamese flavours with Quebec classic French fries and cheese.

Toronto’s vibrant flavour smorgasbord is a natural result of so many cultures coming together in one place. But even “traditional” cuisines are filled with fusion! For example, the tomato on which Italian food intimately depends is native to Mexico and didn’t become Italian until it was brought back to Spain after the invasion, eventually making its way to other European cities. Pizza and pasta are unthinkable without tomato sauce!

Chiles en Nogada, photo by fcastellanos via Flickr (CC BY-ND 2.0)

One interesting example is Chiles en Nogada, a special concoction considered one of Mexico’s national dishes but only served around the holiday of Independence from Spain. Chiles rellenos, or stuffed chiles, is a world favourite of Mexican cooking. This one’s a bit different than the year-round variety. It is made with walnut cream sauce and pomegranate seeds. The gooey sweet and savoury affair mimics the colours of the flag with a trilogy of red, green, and white ingredients. (It is frequently served with parsley for greater flag visibility because the white cream sauce might smother the green chile when served.)

There is some debate about who the inventors of this holiday feast were. But one thing we do know: this is an atypical flavour medley for Mexico. Both walnuts and pomegranates, and the combination, originate in Persia. The pomegranate was greatly beloved in Spain, having moved that way from the Middle East and Arabia with travellers and conquistadors. Recall how some believe “pomegranate” means “apple of Grenada,” which is in Spain. Spain, of course, colonized Mexico, bringing colourful tiles, rosaries, and pomegranates.

From the temple of Solomon to the Independence fireworks of Mexico, to the wine carafes of Toronto’s Persian restaurants, the pomegranate goddess gets around.

Lorette C. Luzajic

“Three pomegranates fell down from heaven: One for the storyteller, one for the listener, and one for the whole world.”

Armenian fairy tale

Pomegranate Juice Stand in Istanbul, photo by Jo Christian Oterhals via Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)