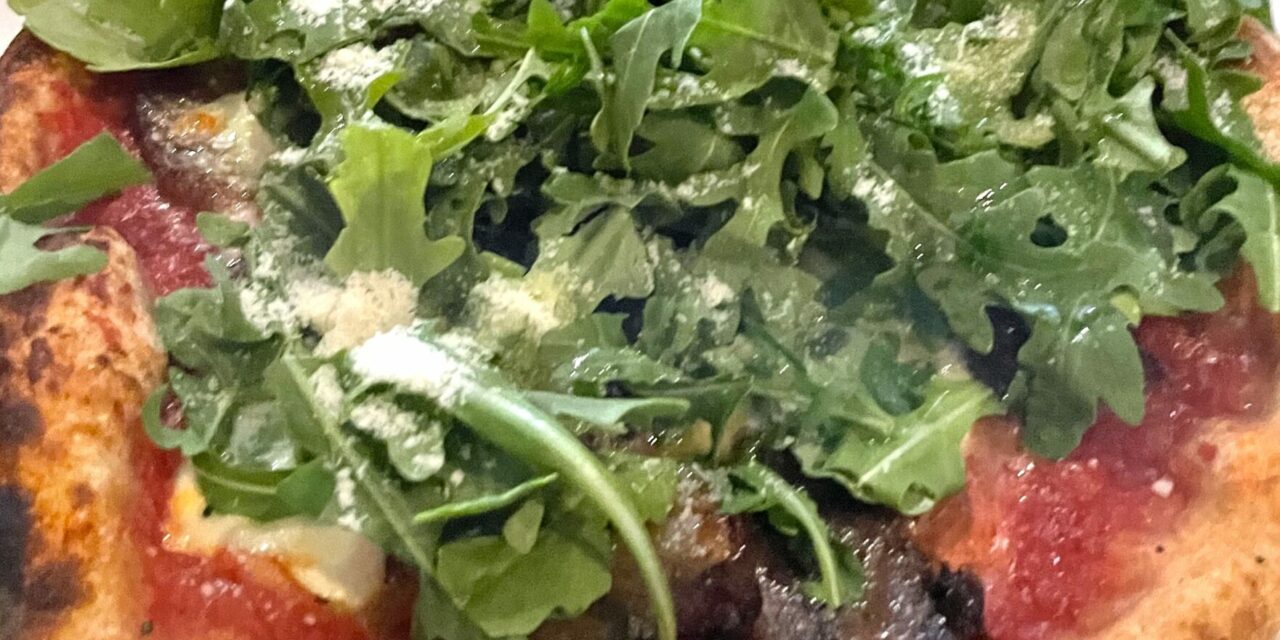

Divine Sourdough Pizza at Bar Mercurio, pizza artist Giuseppe Mercurio. Photo Moshe Sakal.

Pizza: the World’s Favourite Food

“The pizzas keep coming: parmigiana di melanzane, planks of eggplant mixed with tomato and Parmesan, roasted in the wood-fired oven until dense and sticky with flavor, then used to crown a pillow-soft disc of dough; la pinsa conciata, a poetic union of pork lard and fig jam and an ancient goat cheese once on the brink of extinction; calzone con scarola riccia, a featherweight shell of blistered impasto stuffed with wilted escarole and anchovy and a tickle of dried chili.”

Matt Goulding, Pasta, Pane, Vino: Deep Travels Through Italy’s Food Culture

What would other foodies do with three days in Rome? The ancient city is famous for its patios, markets, cafes, and restaurants, each one brimming with historic culinary temptations. The pastries, the pasta, the pesce fritto…

And the pizza. Oh, the pizza.

Pizza pomodoro- just tomato slices and olive oil, sprinkled with pecorino cheese while hot from the oven. Pizza al taglio- squares or strips to go, heaped with toppings, custom cut with chef scissors to suit the demands of your appetite. Pizza scrocchiarella- crispy-style crust, and round, sometimes called tonda romana. Pizza capricciosa: ham, mushrooms, olives, artichoke, an egg and tomatoes. Pizza bianca- just oil, cheese, and herbs, and no tomato sauce.

Pizza by the Gram, in Rome, photography by Reuben Strayer CC BY-SA 2.0 Deed via Flickr

With World Pizza Day approaching on February 9, I can’t help remembering Rome.

I had arranged for a multi-day layover, en route to an artist’s symposium in North Africa, to get the most out of my trip to the other side of the ocean. I decided before I landed that the only way to deal with the heartbreaking paucity of meals I could down in so short a stay was to eat nothing but pizza.

I would do it without guilt, without worry about calories or gluten, and I would turn my eyes away from the pasta and fish and soup. And that’s what I did. Morning, noon, and night. And midnight. I had pizza everywhere I went, whenever I had even the possibility of an appetite. If it was before lunch, I had pizza and cappuccino. If it was after, I had pizza and vino.

Pizza and Wine in Rome, photo by the author

Fragrant basil, acerbic arugula, briny green olives, spicy soppressata, tangy Parmigiana, tender artichokes, bright bell peppers, meaty mortadella, and unexpectedly, pistachios.

It was dreamy. No regrets.

As they say, when in Rome…I’m not the only one gorging on the world’s favourite food, in Italy, its birthplace.

Despite the nation’s embarrassment of riches in food fame, pizza accounts for a full third of tourists’ eating budget in Italy. That’s about 16 billion per year. (Total world sales are estimated around 200 billion per year, with significant leaps annually. Some experts expect this number to more than double by 2030!)

It’s popular with locals, too, with over 60 thousand pizzerias operating throughout the nation. Coldiretti, Italy’s main agricultural organization, estimates they make almost three billion pizzas a year. Though some question the count as being on the high side, safe to say, it’s a LOT.

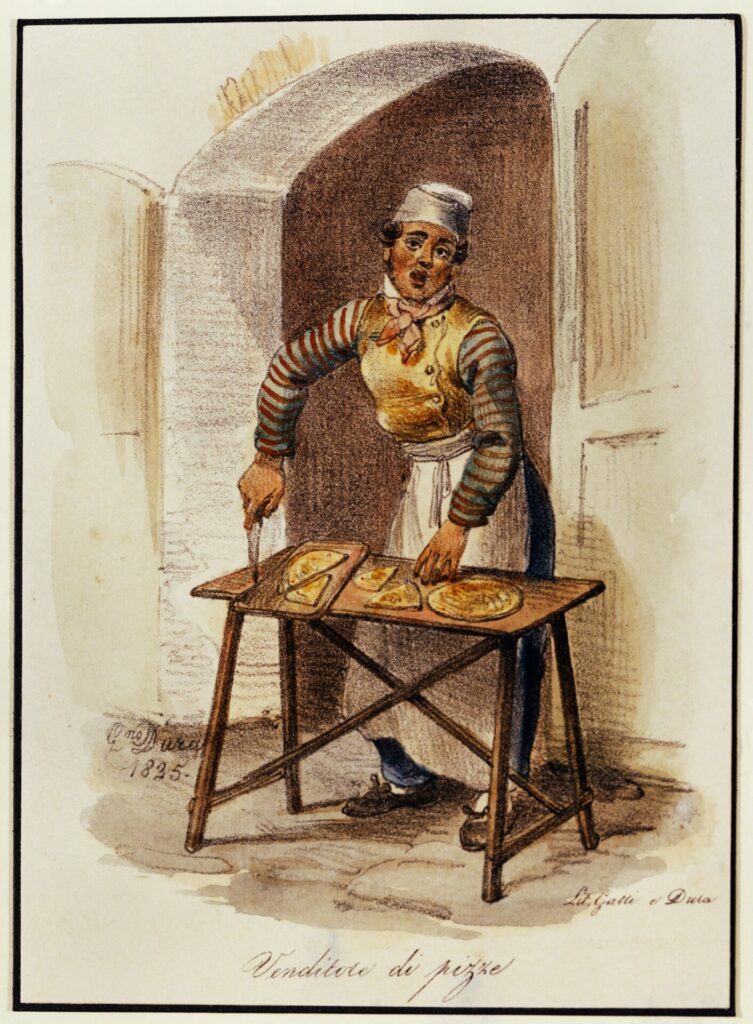

Pizza Seller in Naples, by Gaetano Dula 1835

Many Italians insist that pizza was born a couple of hours away, in Naples. Indeed, Neapolitan style pizza is the world’s favourite. We love deep dish pizza, and thin crust pizza, and in-between pizza, too. We love calzone pizza. We love the big floppy New York pizza slices. We love it fresh and frozen, we love it hot and cold. But pizza napoletana is especially beloved the world over.

Of course, most Neapolitan-style pizza is actually not pizza napoletana. Pizza napoletana is a protected product tradition, on UNESCO’s list as part of an intangible cultural heritage. Real pizza napoletana has very specific requirements. The tomatoes must grow on the volcanic plains of Mount Vesuvius. The mozzarella di bufala campana must be from the milk of the wild water buffalos in the marshlands of Campania, or a reasonable facsimile from cows created and registered according to traditional speciality guaranteed or TSG designation of the European Union.

There are requirements for the flour and ingredient combinations, too, as well as dough thickness. The crust must be handmade without using a rolling pin or machines. Real Naples pizza is baked at a high temperature in a wood stove for 90 seconds or less.

It IS a divine art.

Margherita Style Pizza at Made of Dough, London, photo by Nicodemo Valerio CC BY-NC 2.0 Deed via Flickr

Technically speaking, there are only two kinds of Neapolitan pizza: pizza marinara, and pizza Margherita. The marinara pizza has oregano, tomatoes, extra virgin olive oil, and garlic. The Margherita has basil and mozzarella. That latter was so-called because legend holds it to be the prize pie of Queen Margherita during her visit to Naples. The marinara translates to “fisherman’s wife.” It was traditionally prepared for the husband’s return from the Bay of Naples.

Believers cannot be faulted for their convictions that this heavenly concoction is the site of the incarnation of pizza on earth. Some of the faithful even credit pizza parlour owner Raphaelle Esposito with the invention, and give the year as 1889. That is the year he created the Margherita.

As spectacular as these twin jewels may be, the marinara and the Margherita, it is unfortunately an absurd claim. Naples had had pizza peddlers already for decades and the word “pizza” for centuries. The word means “pie” and what it represents has changed dramatically along the way, to be sure. But it is better to think about pizza as an evolution, rather than an invention.

Depending which aspects of the pizza one counts as a pivotal moment, pizza is either 135 years old or several thousand. It is either Neapolitan or it is Roman, or it is Persian, or Greek, or Egyptian, or Chinese. It also depends on your definition. For me, the marinara is delicious bruschetta that pairs gorgeously with a nice glass of Garganega, but there is no such thing as vegan pizza in my book. Most people would call pizza without tomato sauce something else, but tomatoes were Mexican, not Italian, until a few short centuries ago. People all over the world were putting cheese on bread, but is a cheese sandwich the same thing as pizza? If you melt it, does that seal the deal?

Many people credit the Chinese as the true inventors of pizza. But this is really just an example of a small detail of gossip “going viral” in an old-fashioned way. Marco Polo, the intrepid world traveler, tried scallion pancakes while in China, and wrote about them in his diary. Word soon spread that folks in Naples came up with pizza while trying to replicate the recipe for him.

Scallion pancakes may have some parallels to pizza, and they are tasty to be sure. But oven-baked breads covered in oil, meat, vegetables, and even fruits – with or without cheeses- trace back through the Mediterranean, European, and Middle Eastern world several millennia before Marco Polo was in China. Some say it was the Turkish who brought it to Naples, not Marco Polo.

The Pizza Painting: unknown ancient Roman artist, near Pompeii, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

There’s a recently uncovered archeological treasure not far from Rome, that city where I singlehandedly devoured a dozen pizza in less than 72 hours. (I am not, however, the pizza eating champion of the world. That record goes to one Geoffrey Esper, who scarfed down 19 pizzas in ten minutes. Incidentally, this was at the Vaughan Pizza Festival, Ontario, Canada, where I live. I dined, though, on the same grounds where the world’s largest pizza was made in 2013. It covered 13 580 square feet of Rome. Her chefs nicknamed her Ottavia.)

In the volcanic debris of Pompeii, close to Naples but part of Rome’s reach in 79 when the volcano erupted, a nearly 2000 year old painted mural was found that has been colloquially dubbed “the pizza painting.” The mural by an unknown Roman artist looks features a classic combination of the Italian table: pizza, and wine.

Art and food experts will both say that the painting that looks like pizza is not actually pizza. This is because tomatoes are so central to how we think about pizza today. The ancient Roman recipe was a little bit different, yes- flatbread covered with cheese curds, honey, veggies, dates and figs. Now, I personally find the idea of raisins and their cousins on pizza abhorrent. But was it pizza? Yes. No, of course not. And sort of.

Not according to the Oxford Languages Dictionary online, however. Pizza is “a dish of Italian origin consisting of a flat, round base of dough, baked with a topping of tomato sauce and cheese, typically with added meat or vegetables.” With this definition, pizza bianca (or white pizza, as opposed to “red pizza” with tomatoes) is not pizza. Nor is pizza marinara, special protected Naples heritage status be damned, for it is naked of cheese.

There are many historians who do acknowledge that this Roman flatbread with toppings is indeed a precursor to pizza. It’s even round!

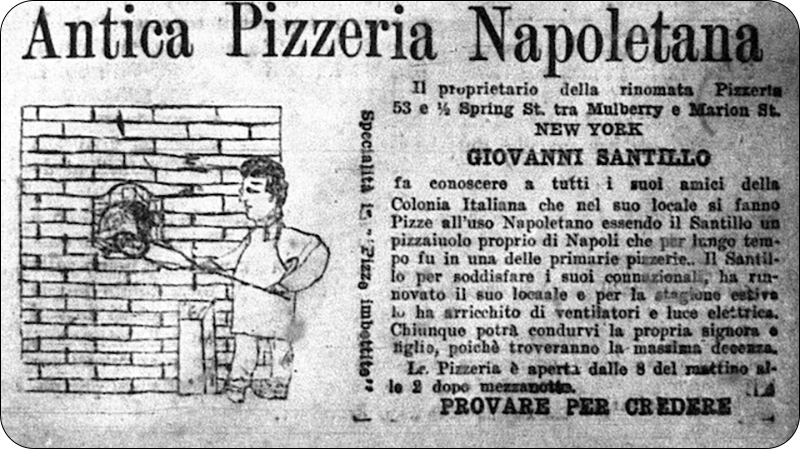

1905 Pizza Ad.

Today everyone wants a slice of the pie and claims their contribution to the invention of the world’s favourite food. It may come as a surprise, but pizza took a while to catch on in America. New York’s Lombardi’s is generally credited as the first pizza shop to open in America, in 1905. (It’s likely that his predecessor was really the first, given an ad in a newspaper for pizza predating him.) Before becoming a restaurant, the place was a grocery that sold “tomato pies’ tied in cardboard with a string. These didn’t resemble Naples-style pies, or our modern classics, but they were tasty and they filled the belly.

It’s hard to believe, but Italian food was shunned by most. There was a wave of Italian immigration to America, Canada, and also to Latin America and elsewhere, in the late 19th century and early 20th century, due to crushing poverty and complex political issues in Italy. As is historically common everywhere, locals were less than welcoming. Italian food was associated with dirt poor labourers. These were the people who brought pizza to New York where they worked on the docks and in train yards, and on farms. They opened small businesses, but these pies were ignored by local populations for some time. Pizza was at first by and for Italian workers. The now famous New York pizza was a simple solution in days gone by for Italians, a quick and affordable lunch during a tough workday. Now everyone knows that! New York style pizza is a gooey, extra large pie, with tomato sauce, Mozzarella, and pepperoni. Making jumbo pizzas with soft crusts meant working men could fold the thing and eat it with one hand, controlling the flow of the oils and sauces while they ate.

New York Style Pizza Wikiuser100, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Pizza was associated with poverty throughout its history, not just in America. The reason the Queen Margherita story become a legend and a turning point was because it offered royal validation to fare that was long associated with peasants. Pizza was basically bread and whatever scraps of cheese or meat or other ingredients could be stretched out on top to feed a family, or the hungry lazzaroni. Lazzaroni were the poorest of Naples, the ragged people, so named because they looked like they were half in the grave. The pizza peddlers took pies from the pizza maker and sold them to the downtrodden and to low wage workers. Some of the pizzas were basically just bread with lard or cheese from cows or goats or even horse milk, or some questionable fish. And when tomatoes first arrived from “New Spain” most were suspicious that they were poisonous, so they were first consumed only by the poor, sliced cheaply onto the pies or made into sauces.

Pizzas were originally described as “disgusting,” as Alexander Lee writes online in History Today. Visitors and foreigners who were not Italian were quite vocal about their revulsion. “In 1831, Samuel Morse – inventor of the telegraph – described pizza as a ‘species of the most nauseating cake … covered over with slices of pomodoro or tomatoes, and sprinkled with little fish and black pepper and I know not what other ingredients, it altogether looks like a piece of bread that has been taken reeking out of the sewer.’”

Different Pizza Slices by Marco Verch CC BY 2.0 Deed via Flickr.

Eventually, of course, word got around about how tasty those sewage slices were. Pizza caught on, sparking small counters at first and corner cafes, in New Jersey, Chicago, Boston, Los Angeles. By the 50s, no one could keep their hands off the gooey goodness and by the 70s, pizza became the official food for family get togethers, for office lunch meetings, church socials, and late night disco dance parties. The delivery model helped spread the good news to every corner of the country. Pizza made its way into I Love Lucy, Seinfeld, and the Archie comic franchise through the always hungry Jughead. Mom and Pop counters and cafes gave way to mega chain pizzerias, and gourmet, luxury restaurants began selling the once scorned slices of the working class. Today, more than 90% of North Americans say they eat pizza regularly.

Some of us have been surprised, travelling to Mexico or Argentina or Brazil, to find the pizza parlour is a deeply entrenched part of the culture there. This phenomenon is parallel to the American pizza story, and the Canadian pizza story, too. Italian immigrants also went to Latin America when they fled their home in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Their delicious foods evolved with the local cultures in these countries, too. While pizza evolved from the New York jumbo classic slice to other urban regional styles, such as Detroit’s deep dish and Chicago’s deeper dish varieties, there are fusions in Argentina, Brazil and Mexico.

Chicago Deep Dish Style Pizza, photo by Amy the Nurse CC BY-NC 2.0 Deed via Flickr

Mexico loves classic Italian Margherita-style pizzas, as well as pies loaded with jalepenos and chorizo, a favourite style of sausage. Peppers, tripe and canned tuna also turn up regularly. Argentine pizza is regarded as a matter of cultural heritage and it is an icon of Buenos Aires, one of the world’s pizza capitals! Argentina has the most pizzerias per person of any country. While Raphaelle was tempting the royal appetites, his compatriots were already loading the ovens with pie in Argentina. Fugazza, after “focaccia” became central to Argentine and Italian-Argentinian identity. These are thick pizzas, sometimes with more than one layer of bread, stuffed and topped with ham, cheese, onions, olives, eggs, garlic, and more. What’s amazing is that there are even more models of “classic” Argentine pizza styles, so we must add “pizza pilgrimage to Buenos Aires” to our bucket lists.

Fugazzeta Pizza in Bueon Aires, at El Cuartito (Since 1934) photography by Wally Gobetz 2012 CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Deed via Flickr

The story repeats itself in Brazil. Over a million Italians headed to Brazil instead of Ellis Island in that great migration. The workers were needed on coffee plantations and in construction projects. Brazilian pizza also has several evolutions that are staples of their way of life, reflecting the merging of the cultures. Pizza de frango com Catupiry is an unusual combination of chicken, tomato sauce, and mozzarella, then drizzled in Brazilian cream cheese. But if you ask for Brazilian pizza, you will get a crisp, thin crust topped with calabrese, ham, olives, eggs, peppers, and possibly, green peas and corn.

Canadian pizza apparently features pepperoni, mushrooms, and back bacon, though I seldom see this. You may be surprised to find out that there are countless regional Canadian pizzas! The east coast has Donair pizza. Montreal has a favourite Rossa Romana or rustica, which is mostly tomatoes and crust and much-loved cold. Regina-style pizza is piled high with deli meats. Desi style is west coast pizza, where South Asian immigrants have tailored their pizza to include cilantro, ginger, tandoori, cauliflower, and paneer. Did you know that Hawaiian pizza is actually Canadian? A Greek immigrant right here in Ontario added the controversial pineapple to the savory pie, wanting to switch things up with something tropical.

What’s your pizza preference? You may guess that my taste is eclectic. I like New York, deep dish, and Naples-style pies. I adore the simple and rustic models, and I love contemporary interpretations and fusions. I love classic ingredients and adventurous ones. I have no interest in conglomerate recipes or chain pies- ugh.

Peppe’s Gorgeous Sourdough Pizza at Bar Mercurio, pizza artist Giuseppe Mercurio, photo courtesy of Moshe Sakal

My favourite place to have pizza in my home city of Toronto is at Bar Mercurio, bar none, a hidden gem near Bloor and Spadina whose colourful pizza maker, Giuseppe Mercurio, is obsessed with the highest quality ingredients. An artist in and out of the kitchen, his hand-milled sourdough crusts are topped with simplicity and authenticity. He uses only the finest cheeses, personally curated San Marzano tomatoes, Calabrese cold pressed olives oils, and meats cured in his private cellar.

It’s the best there is.

Crazy good.

Lorette C. Luzajic

Vintage Valentine c. 1960s