Pistachios in Sicily, photo by Steven dosRemedios via Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0 DEED

Pistachio Paradise: the Ancient Royal Jewel of Mesopotamia and the Mediterranean

Just inland from the sparkling sapphire waves of the Ionian sea, on the island of Sicily, southwest to the toe of Italy’s famous boot, in the foothills of the living volcano of Mount Etna, there are groves of green gold.

Weaving past the Doric-style ruins of ancient temples, through waving birches, beeches, chestnuts, hazelnuts and almonds, and the brilliant sunny yellow Etna broom tree, the fabled Bronte pistachios grow. These are the most prized pistachio’s the world over, sought by epicureans and gastronomy treasure hunters. The Bronte pistachio trees have roots twisting through old lava scars. Small, dense, and rich green in colour, these premium emeralds are nourished in perfect light and the fertile, mineral-rich black volcano soil, coaxed and nurtured and harvested entirely by hand, and sun-dried on the Mediterranean island rocks.

Coasting Mt. Etna, Sicily, photo by Starbuck Powersurge via Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 DEED

The idyllic peace of nestled villages and the bright blue mountain skies is interrupted only by the cyclical chopping staccato roar of circling helicopters. The Carabinieri, Italy’s paramilitary police, are in sky and on foot. Here, they are known as the Pistachio Patrol.

The world’s most expensive pistachios must be protected. The bandits are lone wolf vandals, or bored youth, or petty thieves. But the usual suspects here are not small fry: we are in the land of the mafia, and organized crime rings have their fingers in the pistachio pie. After all, these rare beauties are worth millions of dollars on the market. It isn’t just the end product the pistachio thieves covet: the gleaming green gold nuggets are harvested biennially, representing two years of patience and labour at the mercy of the sun and rain.

(Security detail isn’t unique to Sicily’s Bronte grove, either. In Turkey, home of the world’s most succulent and perfect pistachio baklava, farmers are known to sleep under their trees to protect the fruits of their labour. Sadly, some have been shot. Earlier this year, National Geographic reported on the “pistachio mafia” of Turkey, organized crime rings with grove heists that are then sold on the pistachio black market. And a few years ago, a truck driver was arrested in California for stealing 42 thousand pounds of pistachios for underground resale.)

Pistachios also grow in Tuscany, and throughout Italy and its surrounding islands, pistachios are an integral part of the culinary landscape. People come from all over the world to experience the wonders of fresh pistachio gelato. Pistachio butter is a thing. There is pistachio honey. Pistachio liqueur is a divine nectar. And pistachio cream is in everything, from panettone to cream horns to cookies to tagliatelle or farfalle pasta. The buttery green gems make their way into mortadella, pesto, seafood risotto, and meatballs. Tender pork roasts can be smothered in crumbled pistachios.

Citizen Pie: Pizza Bianca with Pistachio Pesto, by Edsel Little via Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0 DEED

Perhaps the most stunning jewel in the crown is pistachio pizza. Pistachios and local lemons make a surprising and delicious combination on pizza bianca (white pizzas, without tomato sauce.) The nutty delights are often combined with ricotta or burrata cheese. Other favourite blends include yellow tomato slices, asparagus spears, and mortadella.

Poetic types may claim that the blood of the people of Sicily and all of Italy is green with pistachios, and in fact they have been known there for two millennia since the Romans brought them home from North Africa. But the riches of the seed as sustenance and the art of cultivation came from the Arabs during the Islamic invasions and the 9th century conquest of Sicily especially. The oldest evidence of pistachios as food dates back to 6750 BCE in Central Asia, and then we see them in neighbouring Afghanistan. Westwards throughout today’s Iran, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Syria, and Turkey, and then across the northern nations of Africa, pistachios have been cultivated and eaten for thousands of years.

South of Arabia is Ethiopia, land of the Queen of Sheba. Legend holds that her royal highness loved pistachios so much that she made it illegal for common folk to grow or eat them, demanding any tree yields belong to her court.

It is said that pistachio trees were plentiful in the ancient hanging gardens of Babylon. As the story is told, King Nebuchadnezzar ordered engineers to create the masterpiece feat as a gift for his queen, from Medes, who longed for green valleys and pistachios. The Median kingdom was in Persia, which was always and is now the central paradise of pistachios.

Pistachio Plantation Kerman Province, Iran, by LBM1948, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

The United States is the top producer of pistachios in the world, and top consumer, too, with Iran second for the first time, perhaps in all of history. Today America produces half a billion metric tons of pistachio nuts, and Iran around half that. (By contrast, Italy grows only around 4000 tons, or less than one percent of the world’s production.) This is a completely novel development in world history, and is a consequence of the Iranian Revolution in 1979. With the American hostage crisis, when 53 American diplomats were abducted, and the exchange of power in Iran to fundamentalist rule, embargoes on Persian products were a natural part of international sanctions. Tens of thousands of Iranians fled their homeland, with large numbers landing in California (and here in North York, Canada, from where I am writing.)

With massive tariffs and forbidden trade, and a wave of immigrants for whom pistachios were a staple and a way of life, American production was key. Pistachios had first been grown in 1881, and the first commercial crop in the US was in 1976. Throughout the 80s and beyond, those numbers skyrocketed ahead.

Many North Americans have never even eaten the sublime seeds, or they view them as a rare ballpark snack rather than a sundry staple ingredient. But if you’re from Iran, Turkey, or the Mediterranean, or lucky enough to live in a Persian neighbourhood, like me, the passion for pistachios makes perfect sense.

Pistachio Nougat Ice Cream photo by Jules via Flickr CC BY 2.0 DEED

As with Sicily, pistachios make their way into breakfast, lunch and dinner, into sweet and savoury dishes, into hot and cold foods. The delicious nutty flavour naturally complements sweets that are sticky with honey and fragrant with cardamom. “Gaz” is a popular pistachio nougat with rose water. Pistachio brittle is worth a few cavities, too! “Pisteh Shirini” are round ball cookies with pistachios and almond meal, covered in icing sugar. But first, there is spicy pistachio stew, or cream of pistachio-style soups; there are rolled balls of pomegranate and pistachio with meat; there is pistachio pilaf; and countless concoctions with saffron and chicken.

Slow Cooked Moorish Lamb Shank with Pistachios, photo by Stijn Nieuwendijk via Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0 DEED

In addition to their distinctive and delicious flavour, pistachios have an unrivalled nutritional profile. We think of them as a kind of nut, but they are actually the seed of a drupe, an inedible kind of fruit that is discarded in favour of the seed inside. Other drupes work the other way around- we eat the peach and toss the pit, for example. Ditto for apricots and cherries. Other nuts are really drupe seeds, too, including the pecan and the almond. The cashew, too, and that’s a cousin of the pistachio. And so is the mango!

Roasted and Salted Pistachios, by Martin Cooper via Flickr CC BY 2.0 DEED

We revere most edible nuts and seeds for their wide range of important nutrients. But some varieties are actually quite problematic and best as an infrequent indulgence. Nuts and seeds contain phytochemicals (“plant chemicals”) such as naturally occurring pesticides. They are the jaws and claws of plants, intended to ward off and kill pests. No one wants to be eaten, not even humble nuts, after all. Being large predators, we can eat and benefit from what might be enough to harm or kill a worm or bird. But overindulging in some kinds of nuts and seeds can cause a range of gastrointestinal or other kinds of distress. Almonds, for example, excellent sources of Vitamin E and much more, have high doses of oxalates. Oxalic acid can kill you. In smaller doses, we can digest the microscopic sharp shards in oxalates. But they contribute to painful conditions like kidney stones, gout, arthritis, thyroid dysfunction, and more.

It’s probable you’ve never peeled cousin cashew yourself. Cashews don’t come in their shell, because it’s poisonous. Pistachios and cashews are both related to poison ivy!

Fistik Delight, Turkish, photo by Massimiliano Trevisan via Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0 DEED

Pistachios, luckily, have low levels of lectins and other plant toxins. And they have impressive levels of quite a few nutrients, some of which are tricky to get enough of. You’ll get a nice dose of magnesium, potassium, thiamine, B6, manganese, phosphorus, vitamin E, vitamin K, folic acid, riboflavin, iron, zinc, selenium and more. They are high in prebiotic fibre. They have the most zeaxanthin and lutein, essential to the health of your eyes, of all the nuts. They are also one of the most complete sources of protein among plants, containing all of the essential amino acids required by the human body.

Other plant chemicals that are beneficial and not harmful are antioxidants, including phenolics and flavonoids. Antioxidants help mitigate inflammation, damage and disease in the human body. Pistachios have oodles of good stuff. Pistachios show high levels of antiproliferative phytochemical activity against breast cancer cells as well as colon and liver cancer cells.

Chicken and Pistachio Terrine, photo by Alpha via Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0 DEED

Perhaps the only drawback or risk inherent in this food is contamination from bacteria and moulds. The most common mycotoxin in pistachio crops is from aflatoxins, a mould that is carcinogenic to humans. Aflatoxins are common concerns for many foods, especially nuts and grains, and a cause of crop loss and contamination for peanuts, corn, wheat, rice, and more. Every country has standard measurements for regulating aflatoxin levels in food products. The EU’s threshold is the tightest, but all nations monitor mould contamination levels for products at market.

Giant Pistachio Sculpture, New Mexico, photo by Pam Corey via Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 DEED

Another problem of pistachios was red dye, but this is hopefully a thing of the past. If you’re under forty, you don’t likely think of pistachios as red, but older North Americans may picture them as a bright red or pink nut. For some of us growing up, that was just the colour of pistachios, but this was entirely an artificial dye. Curiously, no one is quite certain why we did this, but we have been known to dye foods unnaturally then and now, supposedly to make them look more appetizing. There are a few versions of the story circulating: one is that certain vendors dyed their nuts to distinguish them from competitors. The more widely accepted account is that imported nuts came a long way and looked dry and shrivelled, as dry foods naturally can, and to cover the supposed flaws and blemishes or the bland shell, they were dyed bright red. This was carcinogenic and idiotic. Although some pistachio varieties have a ruddy hue or an earthy purple tinge, they were never fire engine red.

If you’re Italian or Persian you already know that every conceivable culinary combination can be enhanced, and nutritionally fortified, with a crunchy and delicious twist: you can add pistachios to anything. If you occasionally munch on the stuff, or usually stick to peanuts or sunflower seeds, switch things up and toss a handful of pistachios into anything you’re making. Try accenting your next banana bread or carrot cake by adding pistachios. Throw a handful of healthy fats and nutty potassium and magnesium into your salad. Crush them with paprika and green olives to top a salmon, or garnish a meaty stew. Pistachios transform anything into instant gourmet.

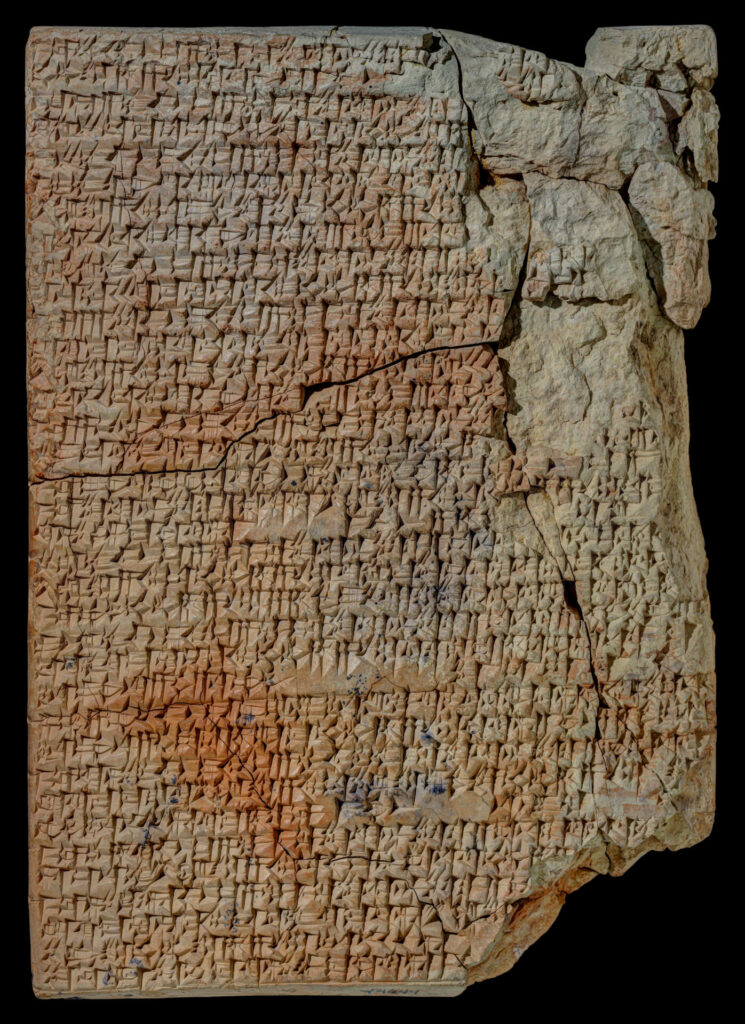

Babylon Cooking Tablets at Yale Babylon Collection, photo by Kwag1980, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

It’s nothing new. We have archeological evidence that we’ve been eating these yummy seeds for almost ten thousand years. But pistachios also featured in the world’s first known cookbook. The Mesopotamian cooking tablets are cuneiform writing on clay, part of a trove of ultra-ancient documents from Babylon, or modern day Iraq, held in the Yale Babylonian Collection. They date to 1750 BCE. One of the oldest recipes in the world ismersu, a simple dessert ball made from rolled dates and pistachios.

It’s literally written in stone.

Pistachio Trees, by Hoca Ali Riza (Turkey) before 1939