Piennelo breed of tomato has its own DOP, is part of the Slow Food Ark of Taste and only grows on Mount Vesuvius.

A dozen Canadian journalists, fighting jet lag, file into Antonio e Antonio, a renown pizzeria in Naples, the city where the dish is said to have been born. They are all tired and hungry, having flown over night from BC, Ontario or Quebec, though most revive a bit after a glass of falanghina or aglianico. One of them finally notices a sort of trellised pyramid of tomatoes that serves as a centrepiece to the table. What fun, they say, a pizzeria that substitutes tomatoes for flowers, and don’t think much more about it.

The next day, the same group are led by their Italian government hosts up a dirt road on the south eastern slope of Mount Vesuvius. We are there to visit a tomato farm, but it’s the middle of November, and as mild as the climate of Southern Italy might be, it’s a dark grey drizzling day and any tomato vines have long been pulled, their stakes piled orderly on the side of the road, and the mountain fields of black volcanic soil have been recovered with a crop of the local brassica, friarelli (which looks a lot like the dark green we call rapini).

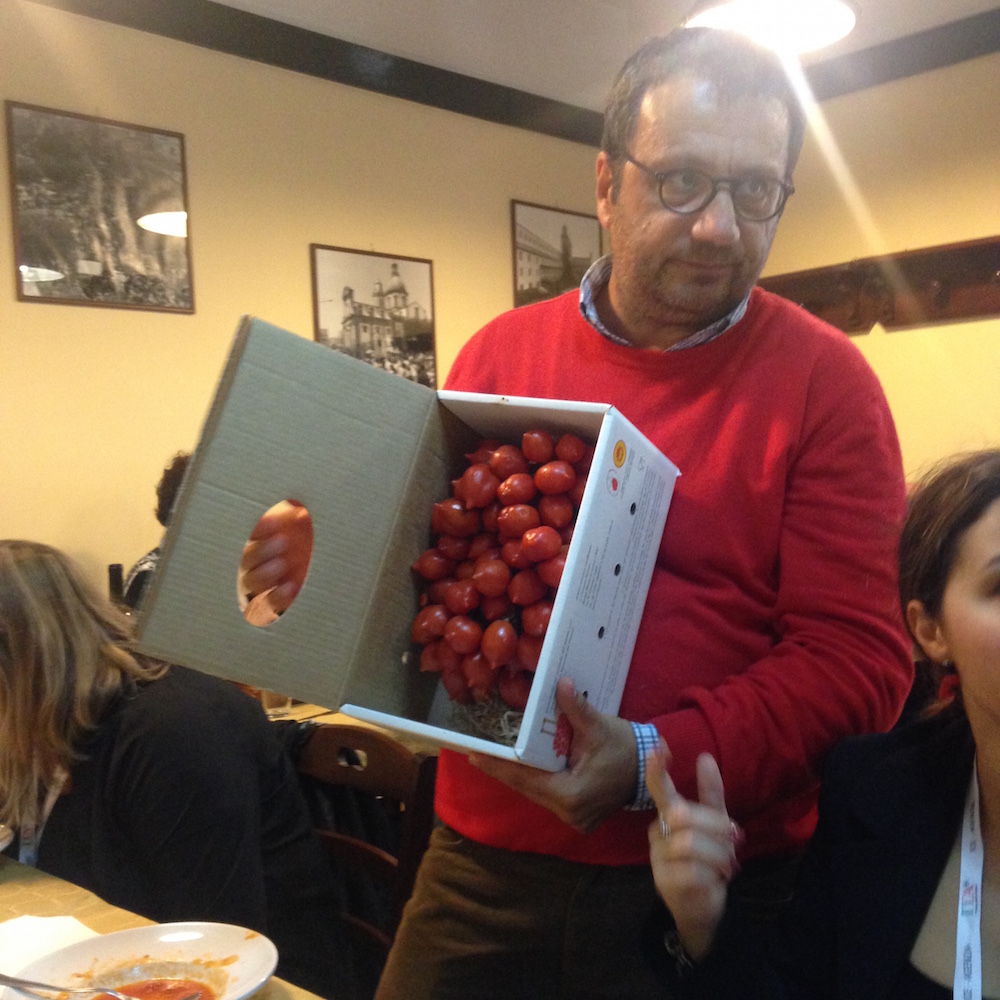

But soon our farmer hosts at the farm of Casa Barone, led by director Giovanni Marino, produce a crate of bright red tomatoes. There the same size and shape as the ones we saw a the pizzeria: like a stout version of a Roma tomato with a pronounced nose, or spike at the bottom. One of the farmers sits down on a collapsible chair in front of a strange frame made of wood, and then he starts braiding the tomatoes into a big cluster. This we are told is the tradition of piennolo, the robust tomato grown only on Mount Vesuvius that takes the Neapolitans through the winter.

Piennolo are harvested in the earl fall like any other tomato. But unlike, say their famous Campania tomato cousins the San Marzano, the piennolo is not immediately turned into a sauce or put into a jar for keeping. The piennolo is a product of 19th Century breeding is such that it’s thick skin preserves the fruit, if it’s kept in a cool place, like a window sill, from September to Easter. Giovanni Marino explains that the rich volcanic soil is the key to the piennolo’s durability. The fields were standing on were as recently alight in magma as 1944, he says. Whatever minerals have been brought up through the earth’s crust make for fruit that lasts, and the official DOP (Denominazione Origine Protetta) piennolo can only be grown in Vesuvius’ volcanic soils.

A very simple sauce made of piennolo tomatoes at Osteria Bettola in Sant’Anastasia, Campania, Italy.

In the drizzly field, we taste the piennolo tomatoes raw. They are good and fresh, but also slightly vegetal with notes that remind us of celery and parsley. It’s a pleasant taste but it confounds us because its novel. (It’s novel enough, in fact, to be part of the Slow Food Ark of Taste.) Soon, we’re off to lunch in the village of Sant’Anastasia at the family run Osteria Bettola. We are served dishes with piennolo in many ways, but the best is a simple tomato sauce with penne (or a local variant). There is a touch of basil, and a sllight touch of garlic, but its mostly bright and lively tomato. We are amazed. This is a sauce that ought to be made in August with fruit just picked from the garden. But it’s November, and we are enthusiastically drinking Casa Barone’s red blend of Piedirosso and Anglianico wine to ward off the chill. We are duly impressed.

This post is part of an ongoing series on the on DOP foods of Campania, Italy. See the whole collection here.

Malcolm Jolley is a founding editor of Good Food Revolution and Executive Director of Good Food Media, the company that publishes it. Follow him on

Malcolm Jolley is a founding editor of Good Food Revolution and Executive Director of Good Food Media, the company that publishes it. Follow him on