The Annunciation, by Carlo Crivelli

Pickle Love

Eat. Play. Rove. with Lorette C. Luzajic

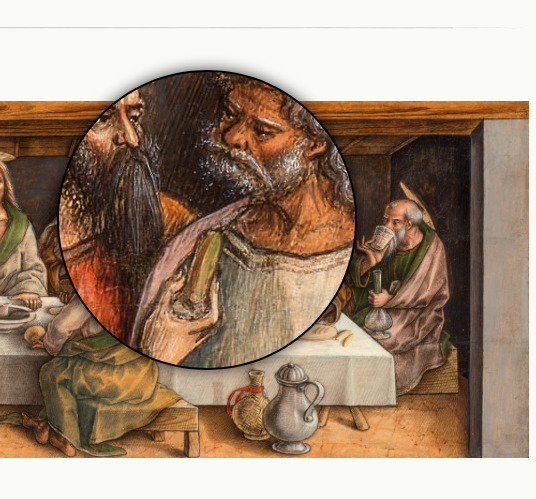

There’s a lot going on in Carlo Crivelli’s The Annunciation, with Saint Emidius. The 1486 masterpiece shows off the artist’s considerable prowess and playful ingenuity when it comes to perspective, geometry, and complex architectural layers. The vanishing point is unusual, angled at Mary to the lower right. Meanwhile, the viewer looks right into the action, through walls into the Virgin’s home and the city street to witness a monumental moment in divine history.

Crivelli was known for the rigorous draughtsmanship and decorative details, a miracle of their own in geometry and design. This work is a veritable latticework of angles and patterns, from the Anatolian carpet motif to the rose-coffered ceilings, grid windows, archways, and ornamental pilasters. Crivelli stood out from other Renaissance painters who shared his exquisite talent for the merging of beauty and mathematics in art because his works were like visual puzzles, perfect, but offbeat. But his real claim to fame are the mysterious pickles in his paintings. Look! Front row centre left, on the floor outside of the Virgin’s window, a pickle.

A pickle followed Crivelli everywhere. It dangles north and west of Mary, the Madonna, swathed in sumptuous greens and golds, in the Ottoni Chapel altarpiece, The Madonna of the Swallow, of 1491. It was there already in the Flemish-inspired precision of the trompe l’oeil work, Madonna and Child of 1480. Indeed, it was there before that, in 1477, in St. James of the Marches. The pickle crowned the good Lord himself, with a plethora of other foodstuffs in The Dead Christ with the Virgin, St. John, and St. Mary Magdalene, with Pickle, in 1485.

Madonna and Child, by Carlo Crivelli

Crivelli’s cucumbers are a conundrum. Fruits and vegetables abound in Renaissance and religious art, but the pickle is more or less unique to Crivelli. Pears and pomegranates, apples and rosehips held rich histories of symbolism in religious paintings through diverse faiths. But the pickle defies all known lore. It appears to be an idiosyncrasy and signature of Crivelli alone, and whatever the artist’s intentions were are long lost, in that garden six feet under.

Speculation and theories abound, of course. Museums favour a breezy description attributing the pickle to the symbol of Christian resurrection. Maybe. The gourd such a symbol, and often appeared alongside the apple, to contrast the fall of humanity and the hope of resurrection. A cucumber is indeed a gourd- sort of. It’s in the plant family, yes, but generally the melon or squash is the depicted stand-in, a fuller emblem of the fecundity and fullness of new life. No other artist to our knowledge used it in this fashion.

Others gender the cucumber symbol and render it phallic, an old boy’s club wink in the sacred virginal artworks. Whether an artist would risk the wrath of his patron church for such a Playboy prank is another question. It’s possible the pickle represented pagan male sexual energy without the tongue in cheek, or hand in pants- a counterbalance for that apple, implicating both male and female in original sin, depicted because the virgin was overcoming the physical with the spiritual. But there aren’t many, or any, parallels for this fruity combo, and the pickle appears even when Mary is not there.

Still others suggest that the cucumber symbolizes the Bible verse in Numbers 11:5: “We remember the fish, which we did eat in Egypt freely; the cucumbers, and the melons, and the leeks, and the onions, and the garlic.” God was feeding his children with dried manna crumbs, and they were longing for pickles and flesh. Could cucumbers serve as a warning not to be distracted from the spiritual gifts? Possibly, but it’s a stretch. Where are the bulbs of garlic and the fish?

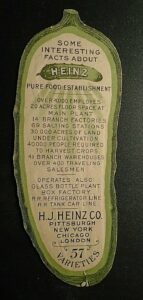

Luis Egidio Melendez

However curious the Crivelli conundrum, perhaps the pickle’s general absence in the artistic record is stranger still. It makes an occasional appearance in a handful of still life works, such as Luis Egidio Melendez’s Still Life with Cucumbers, Tomatoes, and Vessels, in 1774, and a similar work, Still Life with Cucumbers and Tomatoes, with a Knife and Other Kitchen Utensils Upon a Wooden Table, probably in the same time frame. The cuke’s appearance in other artworks is spotty until the advent of the kitscgt Heinz Trading Cards. (Heinz, of ketchup fame, was an innovator in the mass production of pickled foods, and competed with the cucumber itself for the moniker “Pickle King.”)

These sparse manifestations don’t speak to the enduring and ancient importance of the humble pickle.

“Pickling” or “pickles” refers of course to any food preserved through natural fermentation or brine or vinegar. But the pickled cucumber is the king of all pickles, and the one we refer to when we say “pickle.” We don’t mean pickled shallots, pickled eggs, or pickled pepper rings when we say “pickle” without specifying the foodstuff. Occasionally, we’ll call cucumber pickles cornichons or gherkins.

A few hundred years before cucumber was king, pickling as preservation was a thing. According to the New York Food Museum, the civilizations of ancient Mesopotamia pickled their foods, with evidence going back to about 2400 BC. Archeologists believe they invented the process, the same way they invented just about everything, from written language to the map to accounting to the wheel.

It’s difficult to overstate the importance of pickling. In the modern age where the whole world is at our fingertips, and the average family has one or more fridge and freezer and a pantry filled with sealed cans and jars, it’s almost impossible to imagine what food insecurity really looks like. It isn’t just a matter of access or of wealth- in those days, all the money in the world couldn’t keep a dead animal safe to consume until next week’s dinner party. The desert climate held little in way of preventing fruit from rotting if it wasn’t eaten right away.

Pickling was, along with drying and smoking, one of earliest methods of food preservation, to guard against times of draught and famine and poverty. Foods could be pickled with salt and thus preserved for months, one of the reasons why salt was a form of currency in the ancient world, and considered sacred in many societies.

Around 2030 BC, cucumbers arrived from India in the Tigris valley. Pickles as we know and love them were born.

Fast forward 1300 years and move over a bit to China- for some time, folklore claimed the pickle was invented to feed the workers on the Great Wall of China. While the evidence for Mesopotamian pickling predates this era, the pickle for workers is a nearly universal theme in the ancient and modern world. Everywhere you go, the pickle accompanies sandwiches into the office and onto the fields.

By zero, pickles were still going strong in the Middle East and North Africa. Cleopatra, Queen of Egypt, whose beauty was the stuff of legend, famously attributed her glowing countenance to the humble pickle.

The Romans of her day also waxed poetic toward pickles. Pliny the Elder recorded in Natural History that Emperor Tiberius “was never without” the cucumber. “He had raised beds made in frames up on wheels, by which the cucumbers were moved and exposed to the full heat of the sun, while in winter, they were withdrawn, and placed under the protection of frames glazed with mirrorstone.” Julius Caesar, infamous, among other reasons, as Cleopatra’s lover, reportedly gave pickles to his troops to help them survive the harsh conditions of battles. Much later in history, Napoleon did the same.

The word “pickle” comes from the Dutch “pekel” for brine, and indeed “gherkin” comes from the Dutch work “augurk” for pickle, but pickles probably become European by way of the Jewish people.

HomemadeDillPickles, WDnet, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

It is unthinkable that a Jewish deli could exist without the joy of juicy dill pickles, from Brooklyn to Toronto to Paris. With the constantly shifting diaspora throughout Ukraine, Russia, France, Germany, Poland, Lithuania, and beyond, pickles made their rounds as a favourite staple of the Jewish communities. They loved the tangy snap of salt as a way to liven up the bland bread diets among the poor. These and other immigrant cultures brought pickle love to New York and the “new world,” but pickles also came earlier, with the explorers, as pickles were a valuable tool in preventing the dreaded disease of scurvy.

But for all that, are pickles really all that? Cucumbers themselves, while fresh and delicious tasting, have just small amounts of a few nutrients, such as potassium, manganese, magnesium and Vitamin C and K. They are also very low in calories, providing little fuel. With sodium recommendation guidelines in Canada advising 1000 to 1500 mg a day, a couple of pickles could wallop the whole day’s worth in a few chomps.

In an historical context, when people didn’t have canned foods, fast food, or much more than livestock and plants farmed by their own hand, salt was valuable, not excessive. Even today, many argue that we in fact would die without salt and that it is not the enemy we fear, with salt advocates promoting sea salt rather than processed white salt as a valuable multimineral food. Whatever one’s view on salt, in our past life, salt preserved food and killed off much deadlier pathogens.

Even though a cucumber has little in fuel, five to ten percent of our DVA in the important forementioned vitamins and minerals is nothing to sneeze at. Furthermore, a cucumber is 95% water, rare in both desert climates and urban squalor. It is also a rare food rich in silica, which grows and maintains collagen and elastin, connective tissues in your skin and joints. This may be the secret beauty ingredient Cleopatra swore by. Many cosmetic manufacturers use cucumbers in their lotions, but eating them is much more useful to tissue repair. To get silica otherwise, you’d have to eat rocks. Obsidian and granite have comparable amounts of silica.

Arguably the most important factor in pickles is the fermentation process itself and the resulting probiotic cultures. Historically, pickles were fermented, not just preserved. It’s important to note that the vast majority of pickles today are a yay on taste buds but a nay in probiotics- modern salt and vinegar preserves are not living foods. To reap the ancient benefits of microbiome diversity from pickles, make sure you seek out fermented pickles. Anything on the main supermarket shelf will be a bust. Look in the ethnic and gourmet/small batch sections of refrigerated foods, and find cultured bacteria in the ingredients before you buy! Look for pickles with cloudy liquid. (Highly recommended from this author is www.brined.ca.)

Living, fermented pickles with various strains of lactobacillus probiotics provided digestive help, immunity from infections, cellular energy, brain food, skin food, and reproductive benefit, and protection from harmful pathogens inside the body and in other foods.

Whether you eat fermented pickles for health and beauty, or standard dill pickles out of a jar, the pickle is immensely popular and loved. Pickles are a potato chip flavour, an ingredient in an unusual and delicious Eastern European soup (yes, pickle soup), and a condiment on hamburgers. But far and away the most popular way to consume pickles is in the hand, either straight up or as a crunchy complement to a sandwich. Nearly everyone likes a pickle- several studies show that 85% or more of us love them. Our American neighbours consume approximately 20 billion pickles every year!

Circling back to the cucumber’s cryptic presence in Crivelli’s works, it’s interesting to note that pickles appeared in almost all of his paintings. In a triptych, there was a pickle per panel. Is it possible, then, that the pickle was the symbol of universal love, or universal humanity?

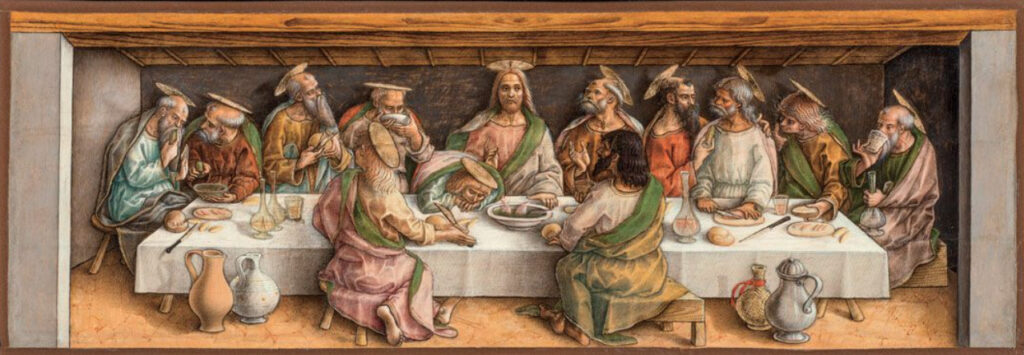

The Last Supper by Carlo Crivelli

Probably not. Whatever it symbolized to the artist is now unknown. Maybe he just loved pickles. He wouldn’t be alone in pickle love! The pickle was so important to Crivelli that he depicted it in The Last Supper. Even the disciples can’t resist the beloved snack, despite the looming doom.

As fellow food writer Kayla Gladysz states so succinctly, in Daily Hive Dished, “When it comes to pickles, you either love them or you’re wrong.”