Wine and Art is an ongoing GFR series on the relationship between the two creative endeavours by working artist and author Lorette C. Luzajic.  It is difficult to hold back, in painting. Always, there is a fear of not having enough there. And then there is too much. It is more difficult than it looks to grant a canvas enough space, and not impose the whole of your manic imagination on it. I am always searching for this delicate balance in my own work, to somehow manage my muchness with some restraint. Just as in writing, when teachers remind their students to take out unnecessary words, an artist must learn to leave out gaudy superfluities. There’s no doubt that busy art can have a kitsch charm, and that sometimes the story is of such magnitude that it’s gotta be big. And it’s also true that austere frugality is far worse than “over salting.” Playing it too safe, too chic, lands you beige walls and pricey streamlined sofas subject to the same cats and kids as anyone else’s. Overly ascetic, clinical style has no place in real life with real people and real spaces. Once again, an interesting parallel presents itself in wine. Big braggadocio proves forgettable in too many giant mouthfuls. You feel swindled by empty promises when the high wears off. And others play it too safe, constantly playing the tired cards of tradition and sophistication. Both the thrillseekers and the purist pursuers of excellence wonder if these crafters think innovation is a dirty word. All of this is what came to mind when I fell spellbound by the work of Robert Motherwell. It wasn’t even the real thing, where the impact of sheer size and volume might prove arresting. It was just a selection of early collages on Pinterest. His trinity of red, black and white with a little text as texture stopped me in my tracks. There was another piece, too, just orange and black, and probably the first time I’ve seen those colours together without thinking about Halloween.

It is difficult to hold back, in painting. Always, there is a fear of not having enough there. And then there is too much. It is more difficult than it looks to grant a canvas enough space, and not impose the whole of your manic imagination on it. I am always searching for this delicate balance in my own work, to somehow manage my muchness with some restraint. Just as in writing, when teachers remind their students to take out unnecessary words, an artist must learn to leave out gaudy superfluities. There’s no doubt that busy art can have a kitsch charm, and that sometimes the story is of such magnitude that it’s gotta be big. And it’s also true that austere frugality is far worse than “over salting.” Playing it too safe, too chic, lands you beige walls and pricey streamlined sofas subject to the same cats and kids as anyone else’s. Overly ascetic, clinical style has no place in real life with real people and real spaces. Once again, an interesting parallel presents itself in wine. Big braggadocio proves forgettable in too many giant mouthfuls. You feel swindled by empty promises when the high wears off. And others play it too safe, constantly playing the tired cards of tradition and sophistication. Both the thrillseekers and the purist pursuers of excellence wonder if these crafters think innovation is a dirty word. All of this is what came to mind when I fell spellbound by the work of Robert Motherwell. It wasn’t even the real thing, where the impact of sheer size and volume might prove arresting. It was just a selection of early collages on Pinterest. His trinity of red, black and white with a little text as texture stopped me in my tracks. There was another piece, too, just orange and black, and probably the first time I’ve seen those colours together without thinking about Halloween.  I happened to be sipping lush, effervescent Viognier at this particular moment of truth, and it had just crossed my mind how some whites make their mark by clearing the clutter and focusing on a few singular notes in perfect harmony. I always like a well-water minerality as the foundation of my white, as if filtered through soil and poured clear. It has to be sharp and direct, edgy, and never wishy washy. Mild is for dish soap, not fuel for the soul. But too much madness in the bouquet, too many notes, proves less than discriminating- a mouthful of cheap perfume.

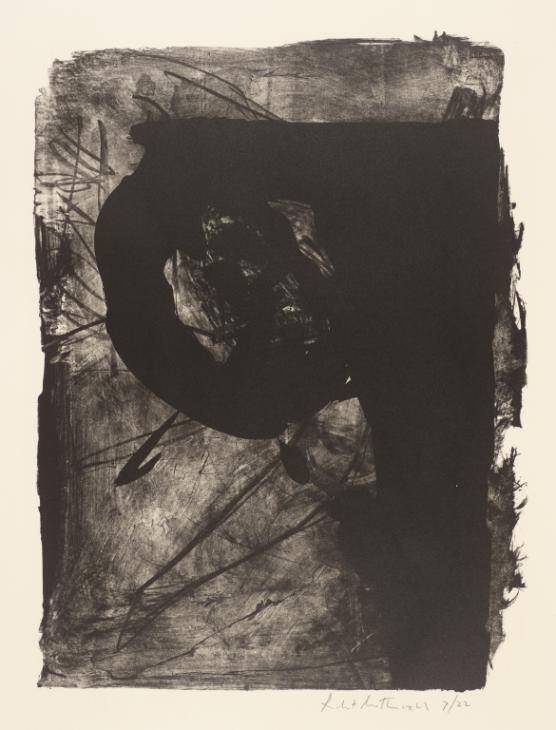

I happened to be sipping lush, effervescent Viognier at this particular moment of truth, and it had just crossed my mind how some whites make their mark by clearing the clutter and focusing on a few singular notes in perfect harmony. I always like a well-water minerality as the foundation of my white, as if filtered through soil and poured clear. It has to be sharp and direct, edgy, and never wishy washy. Mild is for dish soap, not fuel for the soul. But too much madness in the bouquet, too many notes, proves less than discriminating- a mouthful of cheap perfume.  Lost in these deep thoughts, I was struck by the work of Robert Motherwell. I approached from a place of previous neutrality, having never developed an opinion one way or another. Work I’ve chanced to see live has left me curious but underwhelmed. But something in that converging path of Pinterest and white wine took me to the edge of epiphany. Tens of thousands, or millions, might always be absurd when measured with a man and a gallon of pigment. But the artist can hardly help the gallery game. Judged without a price tag, I saw poetry in piece after piece, that danced across my desktop. Anti-modernists might reject the simplicity of gestural abstraction. But like arugula drizzled in nothing but oil and thick balsamic, the reduction of emotion and technique into a few thick and bold swipes by Motherwell has mastered the balance of bold and subdued.

Lost in these deep thoughts, I was struck by the work of Robert Motherwell. I approached from a place of previous neutrality, having never developed an opinion one way or another. Work I’ve chanced to see live has left me curious but underwhelmed. But something in that converging path of Pinterest and white wine took me to the edge of epiphany. Tens of thousands, or millions, might always be absurd when measured with a man and a gallon of pigment. But the artist can hardly help the gallery game. Judged without a price tag, I saw poetry in piece after piece, that danced across my desktop. Anti-modernists might reject the simplicity of gestural abstraction. But like arugula drizzled in nothing but oil and thick balsamic, the reduction of emotion and technique into a few thick and bold swipes by Motherwell has mastered the balance of bold and subdued.  The artist said himself, “One of the most striking of abstract art’s appearances is her nakedness, an art stripped bare.” Even Robert Hughes lauded Motherwell’s art as elegant and educated. Hughes was a brilliant and bitingly witty art writer who notoriously rejected any art not firmly rooted in meticulous draftsmanship.

The artist said himself, “One of the most striking of abstract art’s appearances is her nakedness, an art stripped bare.” Even Robert Hughes lauded Motherwell’s art as elegant and educated. Hughes was a brilliant and bitingly witty art writer who notoriously rejected any art not firmly rooted in meticulous draftsmanship.

“…Motherwell is a painter of superb though admittedly fitful balance who has managed to raise a magisterial syntax of form over an undrainable pond of anxiety…in its breadth, grace, discipline, and lucidity…his art is genuinely Apollonian.” – Nothing If Not Critical (1991)

Translated for the rest of us, Hughes is saying that Motherwell’s best work is beautifully balanced, an orderly language with rules of its own, work that is unabashedly modern but better than the other hacks in the abstract expressionist movement because it is historically self-aware. Hughes notes that Motherwell references Picasso, for example, but his work is not simply appropriation. “Motherwell would also write more knowledgeably about Picasso than most of his contemporaries, critics included,” he nodded.  I’m not sure I agree with him about rationality and order in these intriguing paintings. They are more dreamy than that, each one a Rorschach inkblot, gorgeously imprecise. The quality he is observing is one I see more as withholding or self-restraint. The artist isn’t boasting of technical acumen: his collages and the direct, massive brushstrokes are about chance and space. They are stunning contrasts of bold dynamism and spare elegance, the perfect proportion of frills and no frills. At once they are dramatic and understated. Moving forward while holding something back. This is everything that the best in wine can be. We want innovation with tradition. We want complexity or drama, without overcrowding. We want versatility, flavours that can hold their own next to all kinds of culinary options- but we want distinction and uniqueness, too. Admittedly, such a fine balance is a lofty goal, but its pursuit has given us an interesting array of experiments in wine and art. Striving to make new strides, to break new ground, with the foundational basics of one’s art’s history yields unlimited examples of human creativity. As Robert Motherwell said, “In a way, painting is like wine: it is as old, as simple, as primitive and as varied. Like wine, it is a very specific means of expression, with a limited vocabulary, but vast in its expressive potential.”

I’m not sure I agree with him about rationality and order in these intriguing paintings. They are more dreamy than that, each one a Rorschach inkblot, gorgeously imprecise. The quality he is observing is one I see more as withholding or self-restraint. The artist isn’t boasting of technical acumen: his collages and the direct, massive brushstrokes are about chance and space. They are stunning contrasts of bold dynamism and spare elegance, the perfect proportion of frills and no frills. At once they are dramatic and understated. Moving forward while holding something back. This is everything that the best in wine can be. We want innovation with tradition. We want complexity or drama, without overcrowding. We want versatility, flavours that can hold their own next to all kinds of culinary options- but we want distinction and uniqueness, too. Admittedly, such a fine balance is a lofty goal, but its pursuit has given us an interesting array of experiments in wine and art. Striving to make new strides, to break new ground, with the foundational basics of one’s art’s history yields unlimited examples of human creativity. As Robert Motherwell said, “In a way, painting is like wine: it is as old, as simple, as primitive and as varied. Like wine, it is a very specific means of expression, with a limited vocabulary, but vast in its expressive potential.”  Lorette C. Luzajic is a Toronto writer and artist. Her collage-centred paintings use mixed media to explore ideas from art, literature, history and culture, always fascinated by the intersection of human creativities. Exhibition of her work is ongoing throughout Toronto, including such venues as the Spoke Club, the Royal Ontario Museum, the Flying Pony Gallery, Toronto Outdoor Art Exhibition, and the Artist Project, and it has been shown in Belfast, Brisbane, Los Angeles, Edinburgh, and beyond. In addition to occasionally writing about her other passions, food and wine, she is the author of more than ten books of poetry, short fiction, and essays, including Funny Stories About Depression, Fascinating Artists, and Kilodney Does Shakespeare. She is the editor of the new online journal, Ekphrastic. Visit her at mixedupmedia.ca. Photo by Ralph Martin.

Lorette C. Luzajic is a Toronto writer and artist. Her collage-centred paintings use mixed media to explore ideas from art, literature, history and culture, always fascinated by the intersection of human creativities. Exhibition of her work is ongoing throughout Toronto, including such venues as the Spoke Club, the Royal Ontario Museum, the Flying Pony Gallery, Toronto Outdoor Art Exhibition, and the Artist Project, and it has been shown in Belfast, Brisbane, Los Angeles, Edinburgh, and beyond. In addition to occasionally writing about her other passions, food and wine, she is the author of more than ten books of poetry, short fiction, and essays, including Funny Stories About Depression, Fascinating Artists, and Kilodney Does Shakespeare. She is the editor of the new online journal, Ekphrastic. Visit her at mixedupmedia.ca. Photo by Ralph Martin.