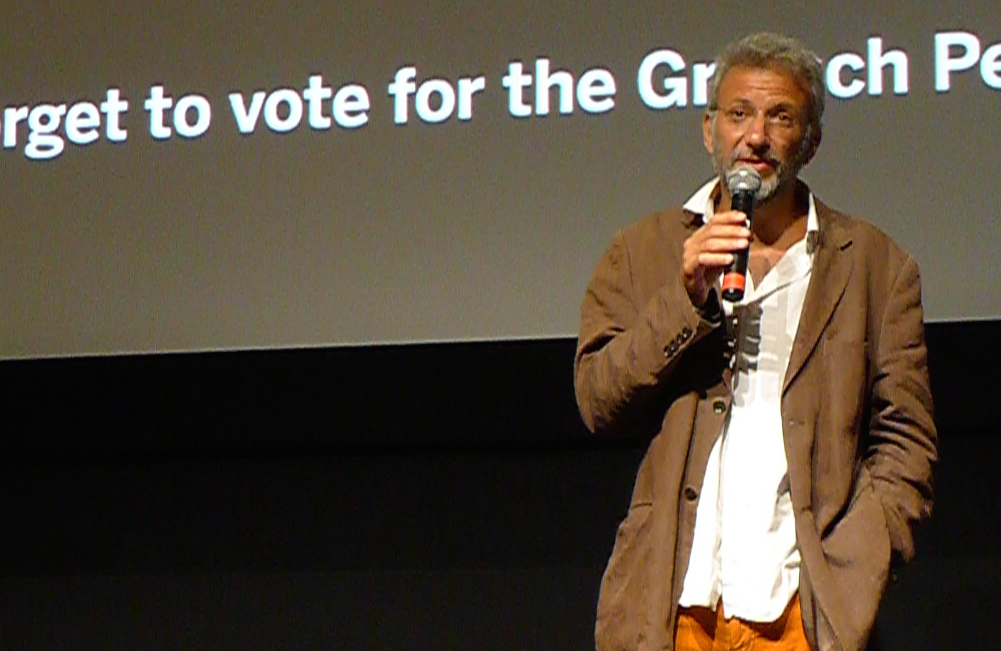

Filmmaker Jonathan Nossiter was in town this week to show his new documentary, Natural Resistance at TIFF. He spoke about the movie, which tells the story of a group of Italian natural winemakers, to a mix crowd of journalists and fans at an event at The Italian Cultural Institute on Tuesday. Speaking without notes, Nossiter gave an impassioned plea for environmentally responsible and non-interventionist wine making.

Nossiter’s previous wine documentary, Mondo Vino, caused quite a stir when it was released a decade ago. Then, Mondo Vino was a sustained argument against the globalization of wine, the influence of the critic Robert Parker, and the loss of vins de terroirs, or wines that taste of certain place. Much has changed in the world of wine since 2004. While Mr. Parker still holds great influence, and there is no shortage of manipulated wine on the market, wine culture has grown and consumers’ knowledge and sophistication has grown with it. And yet, in Natural Resistance and conversation, Nossiter sees the forces of industrialization and homogenization as prevalent as ever, and celebrates the natural wine movement as beacons of hope and resistance against them. At the institute he said, “Basically, we haven’t been drinking wine for 50 years, they should just call it an alcoholic beverage made from grape juice” and decried wine made by conventional means as insipid.

Natural wine is a term of art, its precise definition has not been set or codified. Generally speaking, a natural wine is one which has been made without additives of any kind from grapes grown without chemicals. Nossiter does not define the term in Natural Resistance, and does not seem particularly interested, at least as a filmmaker, of what happens in the cellars of the four wine makers (or wine making families) he profiles in Tuscany, Emilia-Romagna, The Marche and Piedmont. This seems worth noting since among the (admittedly small) world of wine professionals and dedicated enthusiasts natural wine is something of a wedge issue, with many skeptics (for instance Robert Parker) as well as fierce defenders, like Alice Fiering. the film maker, who freely admits his wine maker subjects are also his friends, is instead focused on dirt.

“The key to wine flavour is mineral salts,” Nossiter explained at the institute. Healthy soils, he went on say, encourage long roots on the vines that grow in them that reach down into the bedrock in search of nutrients. Micro-organisms which fix and allow the nutirents to be absorbed by the roots play a key role. When soils are exposed to fertilizers and irrigation, the vine roots don’t grow deeply. And when soils are exposed to herbicides and pesticides, the micro organisms are killed off, which further increases the vines’ dependence on chemical fertilizers. Nossiter’s argument is that the only wines that actually taste of terroir, that are more than “an alcoholic beverage made from grape juice”, are the ones grown in healthy soils. Natural wines, by at least this definition, are he says, “real wine, not a freak show.”

Nossiter calls the wine makers in Natural Resistance “a new kind of peasant” and characterizes the natural wine movement as “democratic”. Much of Natural Resistance deals with the natural wine makers’ fights with their respective DOC’s, the consortia of growers in the region who decide how wines must be made in order to be allowed to be labelled with a designation like ‘Barolo’ or ‘Chianti Classico’. Wine importer Rob Groh from The Vine Agency, was on hand at Nossiter’s talk. At the recpetion that followed, Groh poured wine from Pacina, one of the wineries featured in the film, which gave up its DOC status so they continue to make wine naturally. Nossiter, who praised Groh for “refusing to participate in the corporate economy” by representing wines on the basis of distinction, shook his head as he described the irony that a wine made traditionally could be stripped of its status: “This wine tastes more like a Chianti than any other, but they can’t put it on the label.”

As of Tuesday, Nossiter was searching for a North American distributor for Natural Resistance and hopes it will be released to theatres this spring.

Malcolm Jolley is a founding editor of Good Food Revolution and Executive Director of Good Food Media, the company that publishes it. Follow him on Twitter or Facebook.

Malcolm Jolley is a founding editor of Good Food Revolution and Executive Director of Good Food Media, the company that publishes it. Follow him on Twitter or Facebook.