Malcolm Jolley chats to Norman Hardie about exporting Ontario wine and the VQA Tasting Panel.

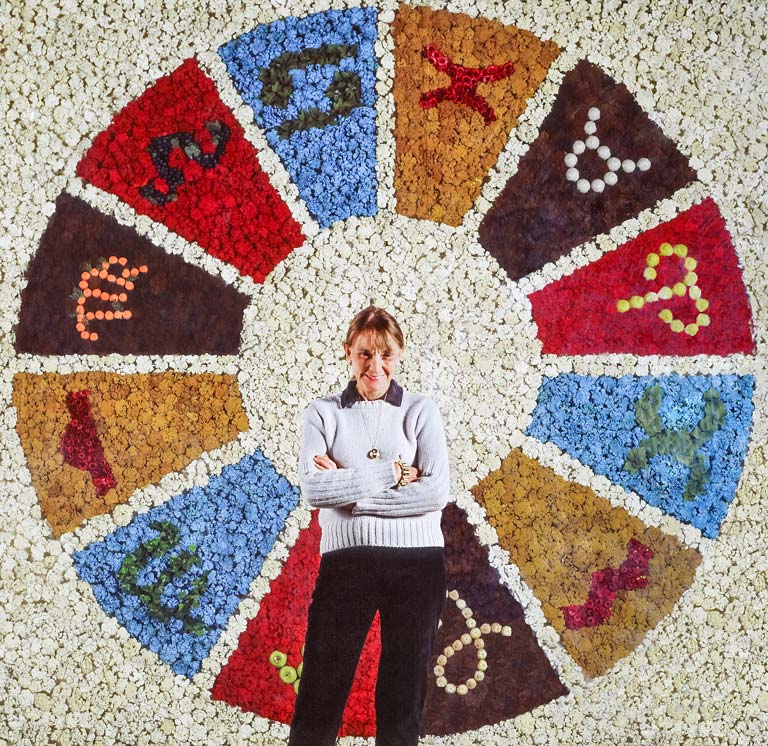

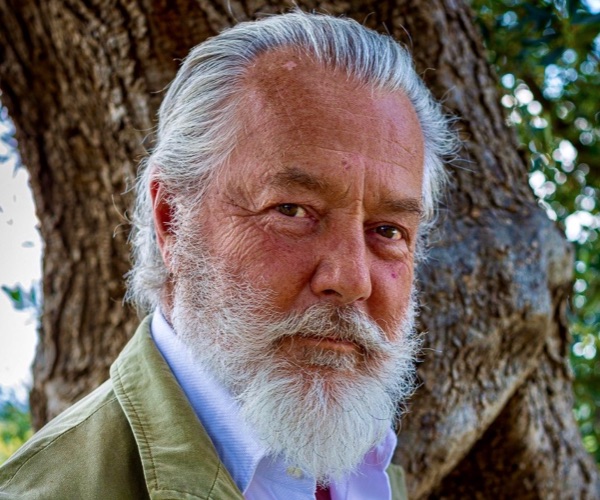

If you want to talk to Norman Hardie, you’ve got to get him on the phone. Or, more likely, he’ll get you on the phone while he driving somewhere between the vineyards of Niagara, his flat in Toronto, his winery in Prince Edward County or his client restaurants in Ottawa or Montreal. Or he might be coming back or forth from the airport, arriving or departing from a trip promoting his wines in a foreign city where they’re sold like New York, London or Tokyo. True to form, Norman Hardie was in his car when he called me one afternoon this week to chat about some press he’s gotten lately about selling wine in export markets.

Full disclosure: Norman Hardie, who I (and everyone who knows him) call Norm, is a friend and a supporter of Good Food Revolution, as his winery is a Good Food Fighter.

The first thing Norm told me when he called was something I knew already, that he had been the subject of the BBC World News story embedded below.

Can’t see the video? Please click here.

Norm was pleased, the BBC story has immense reach around the world. A friend of his texted him that day from her hotel room in Budapest, where she’d just seen it on TV. As he explains in it, the volume of his export business is small, but its significance at home is great because Canadians value international recognition so fervently. Norman Hardie is no exception to this rule, and when he planted his vines in The County nearly 15 years it was with the intention of making wines recognized for their quality around the world, as much as at home. He’s been successful at both, selling out his wines close to home in Ontario and Quebec, but also across Canada from Newfoundland to Alberta, and finding praise from international luminaries from Jancis Robinson to Matt Kramer. The BBC piece was another milestone on the road to increasing international recognition, but what Norm Hardie really wanted to talk about was what could be done with that recognition.

In April this year Norm received an OHI Gold Award in honour of his contributions to the hospitality industry. Fresh from a trip to Europe (he had literally driven from the airport to the gala dinner), Norm used his acceptance speech to tell the crowd the same thing he was telling me over the phone, that Ontario wine is having a moment, and the success that he’s had abroad presents a critical opportunity for all of the province’s producers to make a global impact.

If you watch the BBC News story, or if you’ve been to a winemaker’s dinner with Norm, or if you’ve visited the Prince Edward County winery when he’s there and has time to show you around, then you know the story that Norm tells and its star: the soil. Norm made a very conscious decision to return to Canada, after helping to make wines around the world, because he thought he could make world class wines from the limestone soils of Niagara and Prince Edward County. Of course, he has. But his point, and I don’t think it’s false modesty, is that he can great wines because we have great soil, and whether he’s talking to a BBC reporter, local fans at a Toronto restaurant or the Prince of Wales, he will promote this place before he promotes himself, or is acuity in the cellar. He is happy for his boat to rise with all the others with the tide, and in the spirit of enlightened self-interest is as keen to promote the general reputation of Ontario fine wines as he is his own in particular.

So, all good, right? Well, not quite because Norm called me to talk about more than the BBC piece. He also wanted to talk about a piece published a few weeks ago in the National Post that ran with the headline ‘How bureaucracy is keeping Ontario’s best wine off liquor store shelves and nowhere near your dining table‘. The story was written by Claudia McNeilly, a young Toronto-based food writer who is not afraid to court controversy. The article, or column, combines an account of a visit and tasting with Norm at his winery and his views on the VQA Quality Assurance ‘sensory evaluation‘ process, colloquially known as the VQA Tasting Panel. He’s not a big fan, having had to fight and appeal on several occasions to get one of his wines ‘passed’.

The article created something of a Twitterstorm, garnering strong criticism and point by point refutation from John Szabo MS. Szabo’s critique and complaint of McNeilly’s piece was focused on factual errors and apparent misunderstandings about how wine is both grown and made in the article. It was not directed at McNeilly’s (and Norm Hardie’s) view that the VQA Tasting Panel ought to be discontinued. Norm was calling me because he thought the controversy about errors in the piece was obscuring the larger debate about the relevance of the tasting panel at this point in the development of the Ontario wine industry. (A point Szabo himself, albeit ambiguously, made on Twitter, when he complained that the felt the errors in the article “compromise an important discussion.”) Norm told me that despite the errors in the piece, “I stand by it.”

“In order for Ontario wine to go forward,” Norm said, “change is needed.” He saw a connection between the BBC piece and the National Post article that I hadn’t caught, and he explained. The wines that caught the attention of the international press (and the local press too, for that matter) are not middle of the road wines, they’re the ones that stand out. He said that at a recent tasting of VQA wines abroad, a well known wine writer was heard to be grumbling that most were “monochromatic”. Then he brought up the example of the Australian wine producers. Until a few years ago, to be eligible for export, an Australian wine had to pass a tasting panel which, like the VQA one, disqualified wines for things the panelists deemed to be flaws or contrary to typicity. For instance the VQA tasting criteria include making sure “the wine is representative of quality wines of its general category”, as one presumes the tastes of the panel determine.

The Australian wine industry is export driven, and the effect of the tasting panel system was that winemakers, whether consciously or not, made wines to conform to the taste of the panel. The result was that many Australian wines in export markets all tasted more or less the same. Agents from the export markets, like Ontario, would often visit Australia and find unique and terroir specific fine wines, only to be told by the producer that they couldn’t be let out of the country. As is the case in Ontario, the tasting panel encouraged homogeneity, to the advantage of larger producers who serve bigger slices of the consumer market that tend to value consistency. There’s no harm in that, but for the industry to “move forward” as Norm puts it, then winemakers need to have the freedom to make wines that they feel express their terroir or technique, or both. In the end, the Australians decided their wines were being perceived as boring, and they got rid of their tasting panel all together.

Regulating wines for typicity through a tasting panel is not unique, of course, to Ontario and the VQA system. Many, if not most, European Union recognized appellations are regulated by a tasting panel made up members of the local consortium. The key difference, as the ‘Super Tuscans’ of Bolgheri discovered decades ago, is that ambitious winemakers in the EU can still market their wines, often with a Protected Geographical Indication designation linked to the territory in which it was made. Ontario producers cannot. Wine made by producers who opt out of the VQA, or a wine that does not pass the tasting panel, cannot claim to be from a VQA designated place, like “Prince Edward County.” (See Jamie Drummond’s 2016 GFR post on the trials and tribulation’s of the non-VQA Old Third winery here.) Perhaps more importantly, there are tax implications, as VQA wines are treated advantageously by the provincial government. John Szabo MS explains the financial importance of VQA designation in a 2016 post at WineAlign.com:

None of this would matter much if obtaining VQA designation weren’t so critical to the financial success of a business. Wines without VQA status (but still 100% grown and produced in Ontario) are forcibly sold at far slimmer margins, under government laws, while VQA-approved wines enjoy significantly enhanced profit margins.

For example, according to a pricing calculator provided by Duncan Gibson, Director of Finance for the Wine Council of Ontario, from a $19.95 bottle of VQA wine sold directly to a restaurant, the winery retains $14.38. The same bottle of wine without VQA designation, sold to the same restaurant at the same price, earns the winery just $9.64, a 33% reduction in profits. Furthermore, non-VQA wines are effectively excluded from the LCBO’s retail distribution network, which leaves only cellar door or licensee-direct sales opportunities. The difference, especially for small wineries, is quite literally the life or death of the business.

This is why, even for an established and top tier wine producer like Norman Hardie, which routinely sells out its production, VQA designation is still important. The power wielded by the tasting panel is consequential.

Norm told me on the call that he’s not looking for a fight. He said, “All of us in the industry want to promote Ontario wine, so sometimes there’s a fear of criticizing something we don’t think is working because we’re afraid it will look like we’re putting down Ontario wine – that’s the opposite of what I’m trying to do.” He also said he understood why the tasting panel was created in the first place: “Thirty years ago there was some awful Ontario wine being made and sold, it was important to establish a quality floor.”

OK, I said back, it’s all fine for you, who trained under some top winemakers and learned both very traditional and modern winemaking techniques and science, but aren’t you worried that getting rid of the panel might result in some really weird and awful wines being on the market? Couldn’t it backfire and hurt Ontario wine’s reputation? His reply was, “Look at craft beer: there’s all kinds of weird and terrible things being made, but look how vibrant successful that model has been.”

Ultimately Norman Hardie is optimistic about his campaign to end the panel, he cited the Australian example again and explained how Wines of Australia successfully pivoted from taste-based quality control to scientific and geographical models. And, he said, he was meeting the the top management of one Ontario’s biggest wine producers next week to discuss reform; an invitation that was warmly received. “We’ve got to do it”, he said before hanging up, “or Ontario wines will end up fumbling into the middle.”