There will be no whimsical displays of Beaujolais Nouveau this year. Freight and fuel costs continue to skyrocket. Global wine bottle shortages persist. As a result, this once cheap and oh-so-cheerful red has become an expensive proposition.

And let’s face it, consumer interest has been waning for years. Sommeliers turned their backs long ago. Even in Japan, Beaujolais Nouveau’s most ardent overseas imbibers, support has been steadily falling away for a decade. An estimated doubling of prices in the market may be the final nail in its coffin.

Though Beaujolais Nouveau may be gone from our store shelves in 2022, that doesn’t mean we can’t raise our glasses on Thursday to salute how far the region has come.

New Wines, Ancient Traditions

The idea of imbibing a freshly fermented wine is neither a new concept, nor specific to Beaujolais wines. In ancient Greece, the Athenian festival Anthesteria, in honour of Dionysus, was celebrated with the wine of the recently completed harvest.

This idea of harvest celebrations lingers in France, with nouveau wine releases throughout the country, from Gaillac, to Touraine, to the southern Rhône Valley – though Beaujolais remains the most well-known and widely exported example.

In the 1800s, wine merchants were already buying just fermented Beaujolais to showcase the new vintage to their brasserie and restaurant clients in major surrounding cities. However, it wasn’t until the 1950s that official legislation was past that mandated the third Thursday of November as the official release date for the wines of the vintage.

How Beaujolais Nouveau Took the World by Storm

Beaujolais’ most recognized household name, Georges DuBoeuf, is credited with creating the global craze for Beaujolais Nouveau. By the 1960s, the cafés of Lyon and Paris had already joined in the fun of racing to see who would receive the first shipment of Beaujolais’ new vintage. “Le Beaujolais Nouveau est arrive” became a call to revelers to join in the simple pleasure of sharing the light, fruity wine.

DuBoeuf worked tirelessly with chefs, sommeliers, and other wine gatekeepers in major markets around the world to extend this tradition. By the 1980s, industrial quantities were being produced. Television ads heralded the arrival of Beaujolais Nouveau in the US, great towers of the stuff appeared in liquor stores across Canada, throughout Europe and beyond.

Perhaps no other export market took to Beaujolais Nouveau, or hung on so long, as Japan. Photos of Japanese merry-makers, bathing in spas overflowing with the wine are popular media images every November.

From Nouveau to Nouvelle… Génération

For a time, as appreciation for the soft, banana-scented Beaujolais fell away, it seemed that region was headed for disaster. Who could take a wine region seriously, who’s major claim to fame was a cheap, quaffing red with zero shelf life? But change was afoot.

The work of Beaujolais’ natural wine pioneers had already begun in the 1980s, under the mentorship of local scientist and winemaker, Jules Chauvet. It would take a further decade for these radical new wines – made without carefully selected yeast strains or protective doses of sulphur – to gain the first timid signs of international interest.

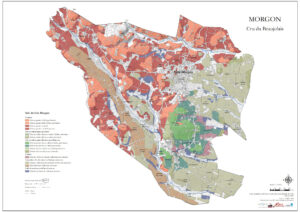

The natural wine movement allowed Beaujolais to re-focus attention on its terroirs and traditional winemaking practices. The merits and distinctions of its ten cru villages were increasingly highlighted with areas like Morgon, Fleurie, and Moulin-à-Vent gaining recognition around the world.

Inter Beaujolais

In 2008, the region began an ambitious soil mapping project that would span nine years. Over 15 000 soil surveys, 1000 soil pits, and 50 field visits were completed. The study led to detailed maps of each Beaujolais appellation, detailing 300 different soil types across the area.

The in-depth knowledge gained from this work has given Beaujolais’ grape growers an incredible tool – informing their decisions on planting, pruning, inter-row, and canopy management in each sector of their vineyards. It is also a great way to communicate terroir – to highlight how different Gamay can taste from one lieu-dit to another.

One Grape, Multiple Expressions

Between its impressive image makeover and the dual trends for natural wines and – more generally – for fresher, lighter, less oak-driven reds, Beaujolais is back in business. The volumes are a far cry from the dizzying heights of the Nouveau days, but a more sustainable quality reputation has been established.

It is a region that is simple for newcomers to get behind. Red wines made exclusively from the Gamay grape makes up 95% of production. Beaujolais can be simplistically summed up as Gamay + granite + temperate climate = light, fresh, low tannin reds with vibrant red fruit and violet notes.

However, for those looking to explore more deeply, the varied topography of gentle hills to vertiginous slopes, myriad soil compositions, numerous meso-climates, and wide variety of winemaking practices yield huge stylistic diversity from one Beaujolais to another.

Here are just some of my many favourite Beaujolais producers, for your Beaujolais Nouveau night celebrations: Mee Godard, Famille Dutraive, Antoine Sunier, Julien Sunier, Richard Rottiers, Château Thivin, Marcel Lapierre, Jean Foillard, Domaine des Marrans, Domaine des Chers.