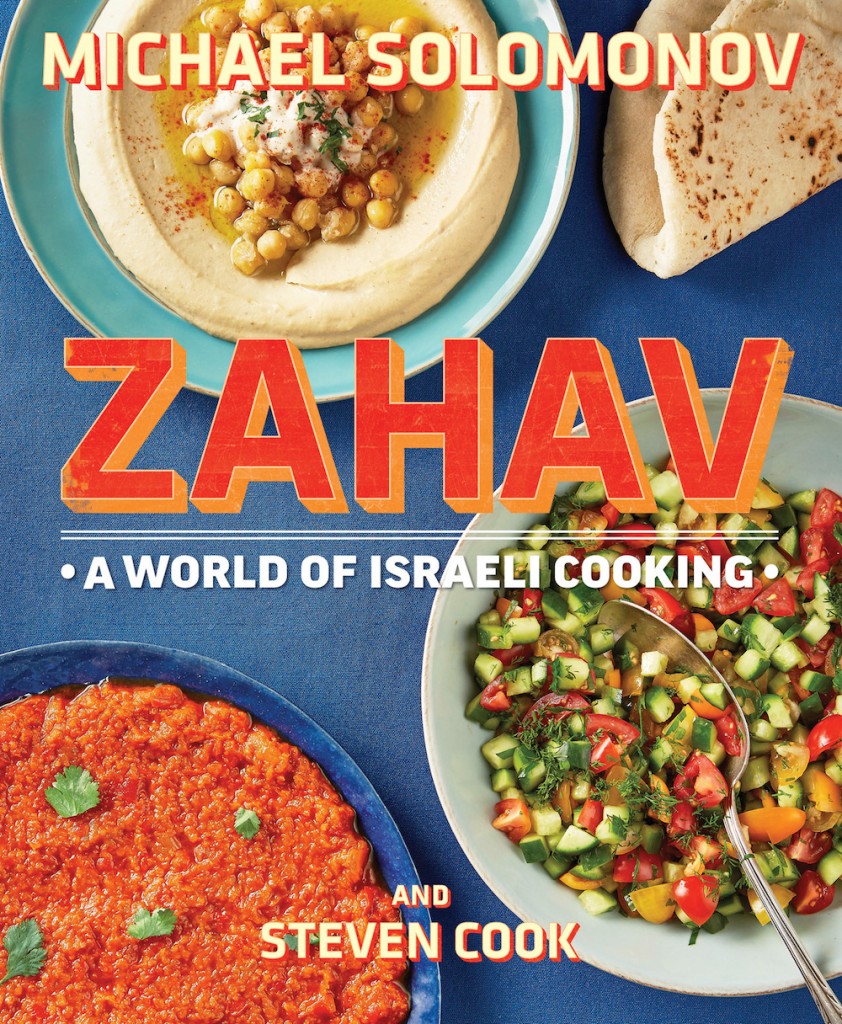

James Beard Award-winning Chef Michael Solomonov’s cookbook takes its name from his Philadelphia restaurant, Zahav and shares an author credit with his business partner Steven Cook. Its subtitle, ‘A World of Israeli Cooking’ describes the modern Israeli culinary scene the American-Israeli chef grew up surrounded by, with influences from all over the Jewish Diaspora and Middle East. Solomonov was in Toronto recently to cook with chef Scott Vivian as part of Beast’s visiting chefs series. I took his visit as an opportunity to sit with him for the interview below.

James Beard Award-winning Chef Michael Solomonov’s cookbook takes its name from his Philadelphia restaurant, Zahav and shares an author credit with his business partner Steven Cook. Its subtitle, ‘A World of Israeli Cooking’ describes the modern Israeli culinary scene the American-Israeli chef grew up surrounded by, with influences from all over the Jewish Diaspora and Middle East. Solomonov was in Toronto recently to cook with chef Scott Vivian as part of Beast’s visiting chefs series. I took his visit as an opportunity to sit with him for the interview below.

This interview has been modified for clarity and style.

Good Food Revolution: Before we talk about Israeli food, and your big beautiful book, can we talk about Philadelphia? In cities like Toronto, we tend to look at the restaurant scenes in places like New York, London or San Francisco, and I think we miss a lot of interesting stories, like what’s happening in Philadelphia. You could be anywhere, why did you choose work and live in that city?

Michael Solomonov: I think, Steve [Cook] and I both ended up in Philly a bit randomly. But Philly is very accepting. Philly is a bit gritty, but because we’re only an hour and a half drive from New York and a two hour drive from Washington, it’s a little bit easier to do business. And maybe a little bit harder, because we’re not an expense account city.

In Philly, our diners expect a lot. Because of the proximity to New York and DC, they’re educated eaters. We have a lot of restaurants, and it’s highly competitive. But it’s also based on very good food and service, there’s no hype. It’s an amazing place to hone your skills and figure out what your role in the hospitality world is, with a lot of hard work. A good write-up is great, but it isn’t going to help you a year later.

But Philly is great, it’s vibrant, accessible, it’s a walkable city. And there are lots of great ethnic restaurants. And that’s where the cooks eat, right? So you kind of have to have that, I think. It’s not super expensive to live there, so that’s good.

GFR: So, people from Toronto should go there and check it out.

MS: They should! I was talking to Scott [Vivian] about this a lot last night. What Philly and Toronto both have is where the employees of the restaurant still live in the city.

GFR: Right. I hadn’t thought of that.

MS: If where you cook, or where you serve, is New York, nobody lives in Manhattan. Even in Brooklyn people are priced out. So, it’s a little bit weird when you’re such an important part of the local culture and sub-culture, but you can’t even afford to live in the city. That’s just strange to me. DC is like that too. It’s very expensive. All the servers, all the line cooks have an hour to get back and forth to work.

GFR: OK, let’s go over to the theme of your book and restaurant. You grew up in Pittsburgh and then your family moved to Israel. The modern history of Israel is very much part of your family’s experience – you brother died in the service of the army. Right now, Israeli food is very much on trend – I’m thinking of Ottolenghi. But you write that when you opened Zahav in 2008 that was not the case.

MS: Up until the opening nobody knew, including our investors and including us, what exactly we were doing. We didn’t know what our position within Israeli cuisine was. It took the restaurant almost closing…

GFR: You write you were a month away from turning off the lights at one point.

MS: Yeah, it was not a good time. Between us, we had tons of years of experience in restaurants and cooking, but we had to learn to be comfortable as restaurateurs, learn actual hospitality and understand what it meant to actually connect with our customers. We were trying to cook food that was awesome in Israel and reproduce it in Philly and that doesn’t work. We’re not in Israel. I’m not an Israeli grandmother, and I’m not cooking in my house. So, the context is completely different. And, it turned out, nobody gave a shit if the food wasn’t exactly what you get in Tel Aviv. And, I’m not going out to every table to tell the customers they’re wrong! [Laughs.]

Also, we’re cooking food form a country in the Middle East where there are at least a few dozen cuisines that make up it’s cuisine. And we’re doing it in Eastern Pennsylvania, so February is a different thing in Philadelphia than in Jerusalem. It’s great because we get to absorb all this stuff: the Yemeni, the Ethiopian, the Russian and look at what we cook with as modern restaurateurs and interpret and transmit it. Even now, it’s getting cold and we’re looking great things like cabbage and pumpkins and apples. So we’re roasting pumpkins and making tahini, or taking pumpkin seeds to stuff inside lamb dumplings. Pumpkin two ways, that kind of thing.

What’s also cool is, because we’re on the outside of Israel, we get to look at all those cuisines as a whole. If you in Israel and you want North African food, you go to the ‘North African restaurant’.

GFR: I think you write somewhere in Zahav the cookbook that there’s no such thing as an Israeli restaurant in Israel to make that point?

MS: Right. Now there are chefs who are trying to do that. But before they just go to France or Spain to train, and they’d come back to Israel and open a French or Spanish restaurant.

GFR: I get the impression that your restaurant is fun to go to.

MS: Yes. It’s definitely fun for the employees, and I think it’s fun for the diners. Our food and service are definitely serious, but we like to say that we are a fine dining restaurant in disguise. The standards are the same, we just like to turn up the music and have a good time.

GFR: My last question was really a statement, but I guess what I meant to ask was, is there an aspect to Israeli food culture that’s more relaxed? I have heard an Isreali expression that you “open a table” when you prepare to serve your guests.

MS: The way that you are served is very casual. There’s a lot of sharing. It’s a lot of small plates. It’s boisterous, it’s not super precise in the way that you eat. And I think you’ve got to roll up your sleeves and kind of get in there. It’s fantastic and a great way to eat and share a meal. And that’s what we try and emulate.

GFR: Talking about the that approach of taking your cooking very seriously while also having a lot of fun, in the Zahav cookbook there’s a riot of colour and energetic images and layout, but it’s also quite serious about technique. There’s a bit of Jacques Pepin’s La Technique going on? You demonstrate and it’s not just pretty pictures on the table. The recipe for hummus is amazing that way.

MS: That was very, very important to us. The way we shot the book was not like an art project. We want people to use the book. We want people to sit down and read the book and enjoy it, to laugh and maybe to cry. We want them to appreciate the content, and love the pictures and maybe have it on their coffee table. But we really want it to be dirty and in the kitchen. We want people to be flipping through it while making the food and taking their own riffs on it. We tried to make it as comfortable for people to read as possible.

* * *

Malcolm Jolley is a founding editor of Good Food Revolution and Executive Director of Good Food Media, the company that publishes it. Follow him on Twitter or Facebook.

Malcolm Jolley is a founding editor of Good Food Revolution and Executive Director of Good Food Media, the company that publishes it. Follow him on Twitter or Facebook.