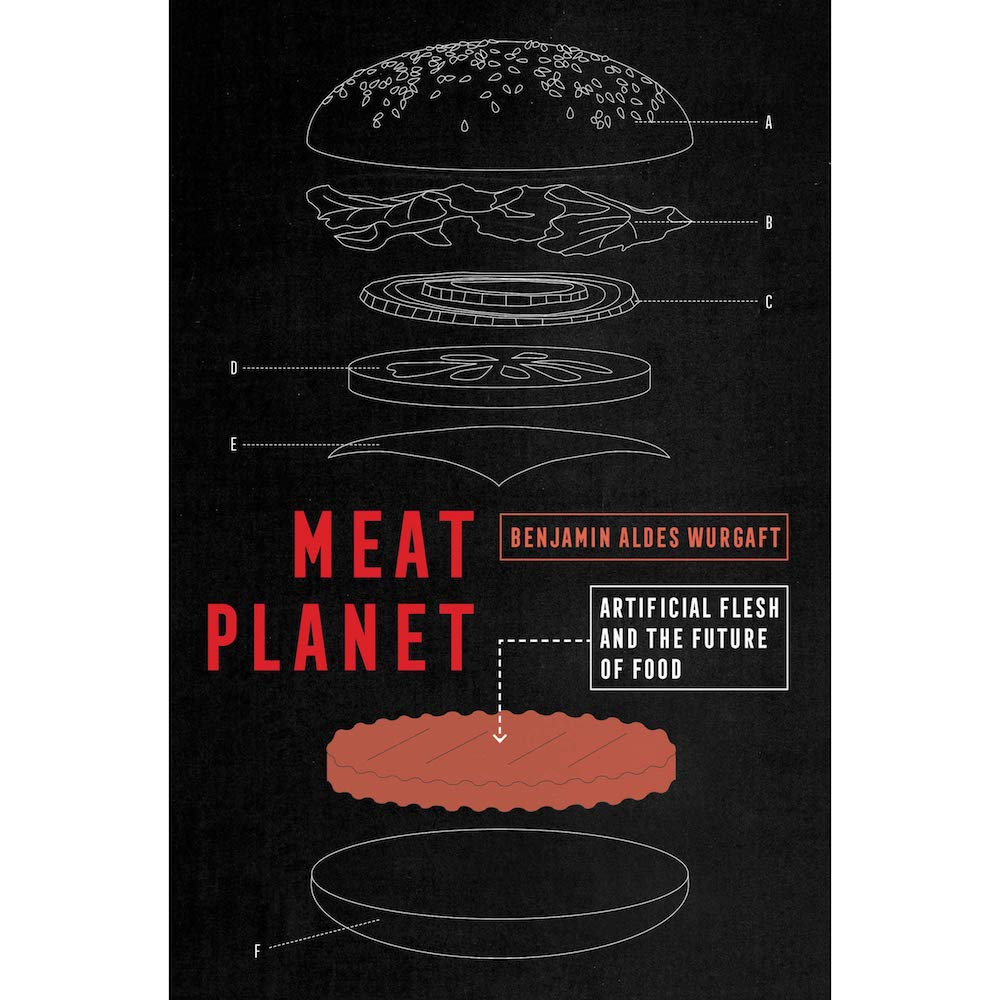

Meat Planet : Artificial Flesh And The Future Of Food – Benjamin Aldes Wurgaft (University Of California Press)

To say that Wurgaft’s academic study of the the emerging biotechnology of in vitrio meat production was densely-packed would be a bit of an understatement. Citing sources as diverse as Freud, Nietzsche, Voltaire, Kant, Foucault, Plato, Harold McGee, Thomas Hobbes, Julian Huxley (brother of Aldous), Poet August Kleinzahler, Physicist Ursula Franklin, Emily Dickinson, Walter Benjamin, Bertrand Russell, Slow Food Founder Carlo Petrini, Peter Singer (naturally), and Poet Percy Bysshe Shelley (an adamant vegetarian, for the record!) as well as many, many others, Wurgaft weaves together a satisfyingly meaty tapestry of the myriad philosophies and morals surrounding the subject matter at hand.

Expertly guiding us through the bewilderingly complex lexicon embraced by those working in the field of cultured meat and related research, the author takes us on a chronological journey from his online observation of 2013’s much-hyped lab-grown hamburger, to where self-professed food futurists and more importantly, opportunistic biotech venture capitalists have taken this idea since then (Spoiler alert : Not very far, really.)

He talks of how Spaceship Earth’s current problems can be seen from orbit, and how those working in the field of in vitrio meat promote their research as being a magic bullet for all the sickness inherent in the polluting and downright dangerous meat production system that we maintain today. However, he is also keen to point out that perhaps it would be naive of us to imagine that it is going to be anytime soon that we enter a utopian “post-animal bioeconomy” as often described by those currently invested in the research and development of such technologies. For now he sees it as more of an abstraction, a technology that has not fully emerged and one that still has a long way to go before such man-made vat-grown foodstuffs become anything approaching commonplace.

As for the animal welfare side of the argument, I was fascinated to learn that back in 2008 PETA, seeking to encourage research, had offered a prize of $1 million US for the first laboratory that could produce a lab-grown chicken nugget; to date nobody has collected the prize. Another stumbling block here is the fact that current growth mediums still utilise the decidedly non-vegan fetal bovine serum, the same as they did in 2003’s infamous $300,000 US “franken-burger.”

I particularly enjoyed one of the first chapters where he breaks down the etymology of the word meat, mapping the semantic shifts around the usage of the word over the centuries, and pointing out that with the proliferation of cellular agriculture we could perhaps eventually see a return to earlier meanings of the word, where it referred to solid food of any kind, and not that necessarily that cut from a carcass.

As well as the many moral questions surrounding the history of our ingestion of meat (Is it natural for humans to crave and eat meat? Meat may have helped make us human; meat may help kill us), Wurgaft also speaks to the connections between meat and gender, patriarchy, modernisation, and the concepts of both affluence and economic precariousness, so there’s a hell of a lot to chew over. To cover it all in a short book review wouldn’t be doing his thoroughly extensive work due justice.

There’s a lot to sink your teeth into here, and I’d seriously recommend this fascinating study of the world of cultured meat for anyone concerned about the future of our food.

![]()

(Four and a half apples out of a possible five)

Edinburgh-born/Toronto-based Sommelier, consultant, writer, judge, and educator Jamie Drummond is the Director of Programs/Editor of Good Food Revolution… And that was a very good read indeed.