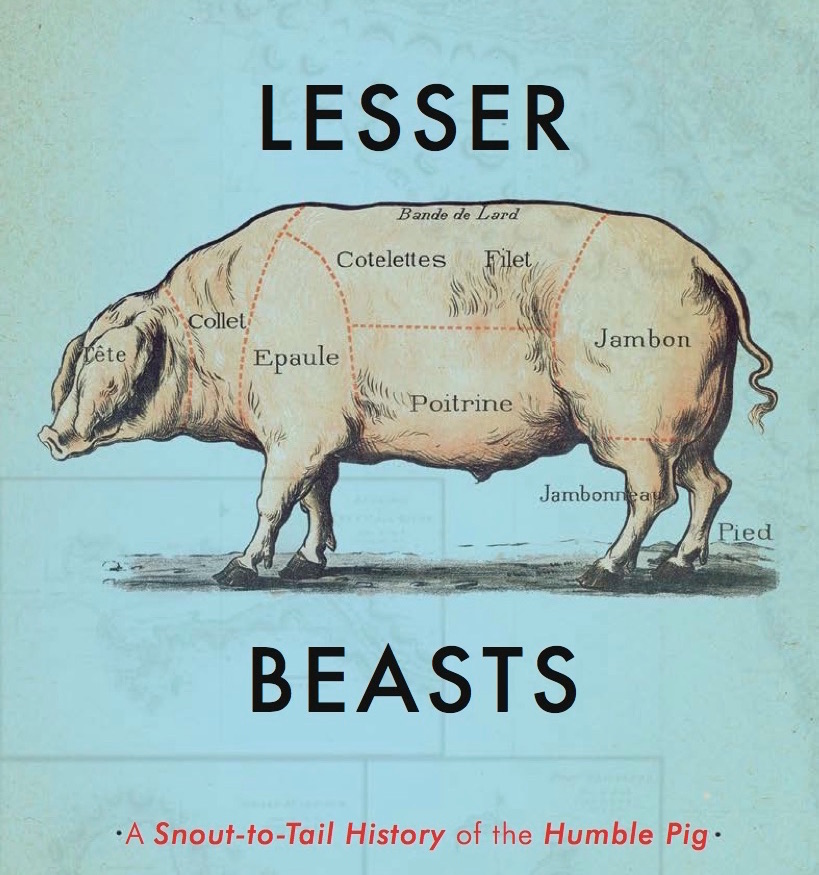

Mark Essig is an American journalist and popular historian who has written a definitive, informative and highly entertaining account of humans’ relationship with swine called Lesser Beasts: A Snout-to-Tail History of the Humble Pig. Essig’s book covers the porcine saga from domestication to intensive industrialization and reflects its authors obvious admiration for the animal and disapointment in the ways it has been, and continues to be disrespected by its masters, us. I spoke to Essig recently on the phone from his home in Asheville, South Carolina.

This Interview has been edited for clarity and syle…

Good Food Revolution: Am I right to say that there is a thesis to your book about how pigs and pork has been perceived through the ages. Can we talk about that? Did you have a thesis in mind when started, or did you discover one?

Mark Essig: Yeah, I think that’s right. And I think it’s better to say that I discovered it. I started out delighted by the story of pigs and fascinated by them. Then, when I dug deeper, I discovered there were similarities in the way people viewed pigs in Egypt in 3,000 BC and the way they did in the United States in 1910 AD.

GFR: The book is called ‘Lesser Beasts’, so is there a sort of class system going on with domesticated animals, then?

ME: I think that’s absolutely right. The curious thing about meat is that it’s the highest status food. Throughout history, the people who were eating meat, of any sort, were the upper classes. But pork was the entry level meat, and as meat eating became more common, the people eating pork tended to be lower class people. You can trace that all the way back to the beginning and the origins of how pigs became domesticated in the first place.

GFR: Right, so one of the problems pigs have had with their image, according to your book, is the content of their diet. It could be a little, um, off putting?

ME: Yes, it could be entirely off putting [laughs]. But to understand that, you need to go back to the ways that pigs were first introduced to the company of people. We know most about the situation in the Near East, in what’s now Syria, Israel, Turkey, Iran and Iraq about 10,000 ago. It’s the same time as crops were first being domesticated.

ME: Yes, it could be entirely off putting [laughs]. But to understand that, you need to go back to the ways that pigs were first introduced to the company of people. We know most about the situation in the Near East, in what’s now Syria, Israel, Turkey, Iran and Iraq about 10,000 ago. It’s the same time as crops were first being domesticated.

It’s useful to compare pigs with something like goats. The best evidence suggests that early hunter gatherers had been hunting wild versions of goats for tens of thousands of years. Archaeologists can go back and look at bone heaps that go back 40,000 years. In the oldest ones, they seem to have been killing the goats indiscriminately: there are young and old bones, male and female. But if you go back to just 10,000 years ago, they seem to have been killing selectively: culling out the young males, which aren’t needed so much to maintain the herd size. So, they speculate that they followed these herds and the process of hunting these animals gradually became the process of herding them.

The culling process doesn’t work with pigs, who are descended from the Eurasian wild boar. They’re woodland creatures that live in small groups. So, instead what they think happened is that the domestication of pigs is tied to the very first permanent human settlements and the beginning of agriculture. When people get together in large groups, they produce garbage. So, we think these wild boar began coming into town to eat that garbage. That would have been the butchery scraps from hunts, rotten grain, burnt food and, what is most repulsive from our perspective, it could mean human feces or the feces from other animals.

GFR: Right: pigs eat shit, or will. So, no wonder the higher casts disparaged them and some religions like Judaism and Islam have prohibition against eating pork.

ME: Yeah, but let’s go back a little bit before we get into that. Pigs didn’t become pariahs immediately. Probably pigs became domestic eight, nine or ten thousand years ago. For thousands of years they were an incredible resource that provided this very useful service of getting rid of the garbage and then converting it into delicious meat and fat. So, for a long time this was not a problem, but then about 5,000 years ago was when some of the first great civilizations were getting started like Egypt and Mesopotamia. Almost immediately you’ll find in the first written records dismissals of pork. It’s still around, but people who could afford to eat anything else avoided it, and pigs became the food of people living on the margins. They became the food of the poor because they were the animals that even the poorest of the poor could raise. All you needed was a little sty next to your house and the garbage on the streets. Pigs were really what we would now call an important source of food security. By the time you get to the formal Jewish prohibition of pork, in the Book of Leviticus, at around abut 700 or 800 BC, that would not have surprised the priestly classes of Egypt or Mesopotamia or the Jews’ other neighbours because they all avoided pork too. It did, though surprise the Romans, once the Romans became the rulers of the region.

GFR: Yes, you write that Greeks and Romans loved pork.

ME: No one has loved pork the way the Romans loved pork. There’s one surviving collection of recipes from the period. In it you’ll find a few recipes for beef, you’ll find maybe a dozen recipes for lamb, but there are just dozens and dozens of recipes for pork; 17 recipes for suckling pig alone. And they really did use just about every part of the pig. They were fans of devouring the womb: there are some horrific recipes that involve beating a lactating sow bloody and mixing up the blood and the milk and the gore. To certain Romans this horrfic dish was the height of culinary excellence.

GFR: Let’s fast forward to the Columbian Exchange and the colonization of the New World, you write that pigs had a key role in that as well.

ME: Yes, and there are some ties to the Romans there. One of the reasons Europeans loved pigs is that they had oak forests, where pigs could roam and, because they are omnivores, they could eat nuts on the ground and didn’t have to survive on just grass and leaves the way that sheep and cows do. They are perfectly home in a forest environment, but as Europe’s forests were being cut down to make way for fields, pigs were actually on the wane by about the 1500s… until they made the journey on Columbus’ second voyage and immediately they found what was pretty much a perfect habitat. When Columbus came over he really brought just about everything you needed to recreate the European diet in the New World: seeds for fruit trees, wheat and other grain crops, melons, and just about anything you could imagine including the full run of domesticated animals. But sheep died almost immediately. Cows eventually did OK, but took a while for them to acclimate to the climate of the Caribbean. Pigs, just as soon as their sharp little hooves landed in the jungle mud started breeding and reproducing at such a rate that within a decade or two, about 1510 or 1520, people started complaining about how many pigs there were swarming around the hills like vermin. Later, when the Spanish invaded the mainland of the Americas, their armies were followed by a swine herd, so they knew they would always have a ready source of food. Historians who have studied this really say that this was one of the keys to the Spanish success in the New World.

GFR: And then later, as things got settled, you write about an whole economy in the United States where pigs are moved around. Raised in one place and sold in another.

ME: I first got interested in pigs because I live in the mountains of Western North Carolina, between the Blue Ridge Mountains and the Smoky Mountains. I moved here about eight years ago and saw in the centre of town a statue of a couple of pigs. I started reading about the history of the area and what I discovered was back in the 19th century, say 1810 or 1820, and right up to 1900 and even a little beyond, from about November through January every winter tens of thousands of pigs would be walked through the centre of town. My first reaction was sheer delight. Everybody heard about cattle drives, but no one has heard about pig drives! But I discovered that pig drives were extremely common. It happened everywhere until there were trucks to pick up pigs at the farm. Here, you had a little corn belt in Eastern Tennessee where they raised pigs, and to the south were the plantations where they had slaves and didn’t grow a lot of food. So you had the supply in Tennessee and the demand in South Carolina and Georgia but mountains in between and the only way to get the pigs from here to there was to walk them. In some cases they would march them for more than 500 miles.

GFR: You also write about how pork can be relatively easily preserved, because of its higher fat content.

ME: Yes, that’s always been a key advantage of pigs. If you talk about why people raise pigs, there are few reasons: first, (as we’ve discussed) they’re versatile and will eat nearly anything; second, they reproduce really quickly – a cow will gestate for about nine months and give you a calf, but a pig gestates for half as long and will give you six or eight or maybe even 12 piglets, who will grow to slaughter weight within a year. And, third, once you’ve slaughtered them their meat will take to salt very well. There are a number of ways you can cure pork, and they all turn out pretty good, especially by comparison to beef or lamb, which tends to taste like shoe leather.

GFR: Lesser Beasts ends with an account of the industrialization of pig farming in the West and now increasingly in China. It’s not a pretty picture. In fact, the treatment of most pigs seems to be very cruel.

ME: Well, the people who are doing it might say differently. I didn’t want to write a polemic. I wasn’t a guy that was terribly interested in the politics of food, I was just fascinated with pigs and the role they played in human history. But I was sort of dragged into the position of critic – I hope not polemicist, but close to a polemicist. It’s hard not to when you learn what has happened to hog farming in the last 50 years. I’m not branding anyone as evil, there were lots of small decisions made over time, but they have added up into something that I think is pretty awful.

If you look at the period after World War Two, land prices were going up, labour prices were going up, and it was becoming increasingly difficult to raise pigs in the traditional way. Throughout North America the way of raising pigs had been that you kept what we would call pastured pigs. That’s considered special nowadays, but that the standard method for the first 150 years of agriculture in North America.

There were a few things that turned farmers away from pastured pigs: one, when land became more expensive it became more profitable to grow crops on land rather than let pigs run around on it; two, the development of antibiotics as a growth promoter and a preventer of diseases for pigs raised in higher concentrations; and then probably the greatest innovation that allowed for intensive hog farming was something very simple called the slatted floor. It meant that when pigs did their business they would trample their own waste into gutters below them which could be flushed out with water. That ended the most disagreeable task [to standard pig farming], which was mucking out stalls. That’s one of the standard chores on a traditional hog farm and I will attest that it is unpleasant.

So, where this has left us now is a situation where, say, 97% of pigs are raised in huge barns, standing on hard cement slatted floors. They will never feel mud or grass under their hooves. The sows have it worst because they live in these tiny little crates, about two feet by seven. Temple Grandin, the animal behaviour scientist, has described it as forcing them to live their entire lives in an airline seat. They can’t really even move around. They’re moved to a slightly larger crate to give birth, but then moved back to the gestation crate to be artificially inseminated again to have another litter, and that’s how it goes until they become less fertile and sent off to be turned into sausage themselves.

It’s certainly changed the my dining habits in that I will no longer eat pork unless I know it was raised on a farm with higher welfare standards. I wouldn’t describe myself as the most ethical or moral person in the world but when you read enough about this you just get grossed out by the conditions these pigs are raised under.

GFR: That’s where you do offer your readers some hope. You point out that notwitstanding the low status or pork historically, among what I call the fooderatti, pigs and pork are actually very much being celebrated and farmed in artisanal ways. Is the pig now at the forefront of a new and better way to eat?

ME: Yeah, I think that’s right. Although, I will raise a caveat. The pig became a sort of cult animal as a reaction to what was the strong dietary advice to avoid all animal fats. Eating fatty cuts from pigs was a way to say, ‘Ha! I reject your advice, I’m going to embrace gluttony,’ and just because pigs do have so much fat on them it was an easy way to do it.

Because cows have a longer gestation period, the raising of beef has not been as thoroughly industrialized as pigs. So, you don’t get as strong a difference between commodity beef and locally raised beef. But the commercial varieties of pork have been so thoroughly stripped of fat and flavour that if you find a pig that has been allowed to run around and is maybe from a heritage breed that puts on a little more fat, you can really tell a spectacular difference between what you find in a supermarket and what you’d find at a butcher who is paying attention to his sourcing.

So, there is reason for hope and people have discovered the versatility of these animals. When you got to farmers markets, what you find is often the people selling you vegetables will have a cooler full of pork as well. That’s a sign that the pig is playing its traditional role. A farmer can keep a pig or two around, feed it the vegetables that aren’t pretty enough to take to the market and let it glean the field after the harvest so it plays its traditional role of converter of agricultural waste. And then, it can be eaten on the farm or even sold, if there is a little bit extra. So yes, I do see pigs playing a bigger role in the new food economy.

But I was torn about how to end this book. On the one hand, there are some very positive signs. When you look at global trends and China in particular the movement is precisely the reverse of what is happening on some farms in the United States, Canada and Europe. They’re phasing out traditional agriculture where pigs are farm waste converters in favour of raising up huge industrial hog operations on the European and North American model. So, while I see signs of hope here, the 1.3 billion pork eaters of China are shifting things in a very different direction.

Find out more about Mark Essig at markessig.com.

Malcolm Jolley is a founding editor of Good Food Revolution and Executive Director of Good Food Media, the company that publishes it. Follow him on Twitter or Facebook.

Malcolm Jolley is a founding editor of Good Food Revolution and Executive Director of Good Food Media, the company that publishes it. Follow him on Twitter or Facebook.