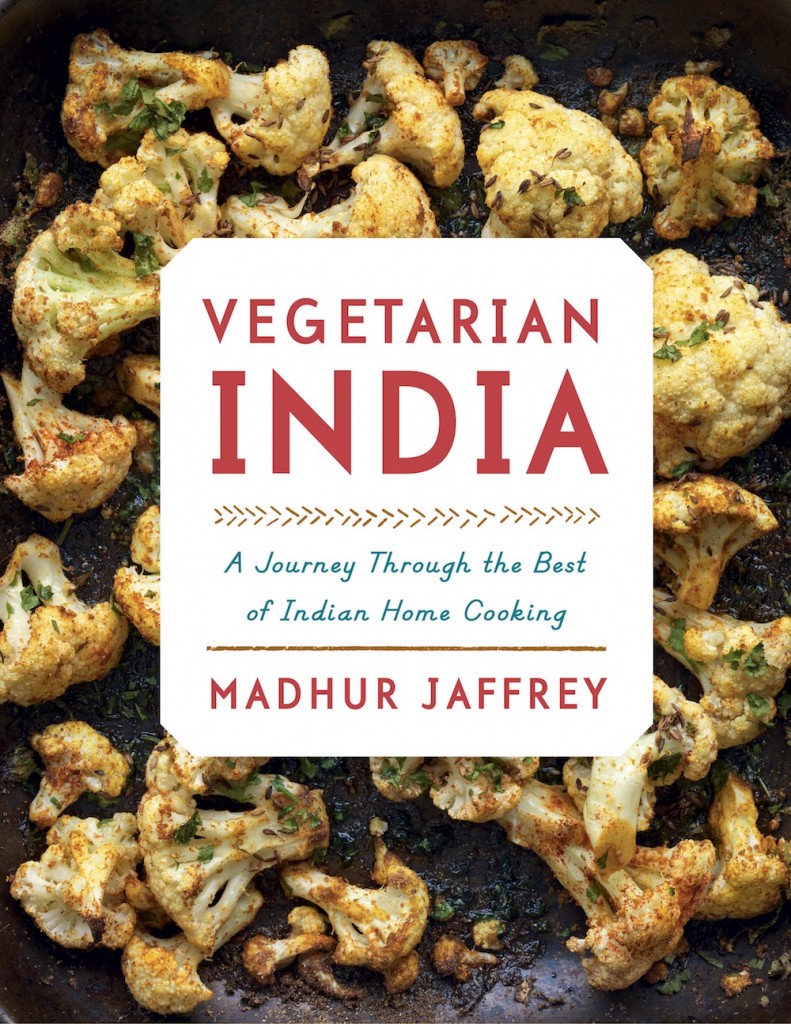

The Actress, author Madhur Jaffrey’s cookbooks, whether focused on the cuisines of her native India or abroad, are legion and have won her a loyal readership and acclaim across the English-speaking world. Her latest book, Vegetarian India: A Journey Through The Best Indian Home Cooking, is surprisingly the first of her’s that exclusively focused on meatless recipes from only India. It dwells largely on the southern regions of the country, and examines how different groups of ordinary people eat. It’s a beautifully shot, lush book brimming interesting flavour and spice combinations. It’s also, like many of Jaffrey’s books, a reference work and a fascinating window into unfamiliar (at least for me) food cultures. I spoke to Jaffrey about Vegetarian India at her Toronto publisher’s offices last week.

This Interview has been edited for style and clarity.

Good Food Revolution: Why this cookbook now? You have written (and sold) many, many books and won many awards and acclaim. What was your motivation to get back at it and write this new one?

Madhur Jaffrey I always feel that there’s so much about India that I don’t know, that people don’t know, and I always feel like I want to go and write it down. I have always been interested in how people eat, how different groups of people eat and what they eat. Where do they sit down and eat it? Do they eat with their families? Do they eat alone? What are the traditions? There are millions of them. I must know these things, and that’s what pushes me to go out there. I think, this is so interesting people will want to know.

GFR: That’s what struck me about Vegetarian India: it’s an investigation. It’s more a work of journalism, than memoir. I assumed you already know everything there is to know about Indian food, but you’ve found out all kinds of new things. How do you start your investigations? Do you just buy a plane ticket and plunge in?

MJ: No, it’s not so easy. The whole business of looking for recipes is much harder than it would seem. You have to set up things. And if you’re going to areas unknown, you have to set them up more carefully. Things don’t pan out very often. Sometimes something seems so sure, and then it all falls apart when you get there. So, you have to have several options and I had to arrange to meet people in these regions that I particularly wanted to get to, through friends, or friends of friends, or friends of friends of friends. It’s quite exciting, because that whole route is a total unknown. When it works, it’s great.

GFR: So, you’re going into strangers’ kitchens. That’s very intimate, isn’t it?

MJ: It is. For example, I have one very good friend in Bombay, Vikram Doctor . He’s a food writer, one of the best food writers. He’s a little bit unsung, but really knows everything. He’s just exceedingly talented, I think. And he’s a person I go to for Bombay, that coast and a little south. He knows his business there. Any question, about the rice harvest, or what are the grains that were used but that have died out, he will know. But even he sometimes can’t help. In the South, I had no such person.

So, I had a playwright friend I knew from years back, and his wife was one of those people that was very knowledgeable about India, a very bright woman and very social. A friend who knoew her wrote to her, and then I wrote to her to re-introduce myself and I said, ‘What I want is six or seven people of slightly different southern background: one from the forested region, one attached to this temple, one attached to this other religion, one from this area, one from that area, if you can, and have them cook in their homes for me.’ Now, that is a very tall order. Well, she found them and she set it up.

GFR: And did you use every recipe?

MJ: No, no. I couldn’t: they all cooked 20 things

GFR: But everyone got in the book. It would be awkward if someone didn’t?

MJ: Yes, they are all in, but I have that trouble all the time, where you think, Oh my God, they cooked for me for nothing. I am having that trouble right now writing something on Crete. I can’t fit one person, who gave so much of her time to me. But I am trying.

GFR: I think Vegetarian India is very much on trend. Everyone wants to know what to do with their vegetables. Why did you decide to do vegetarian?

MJ: Well, partly because I have a vegetable garden, and I had started a book called ‘From my Kitchen Garden.’ But Sonny [Mehta, Editor-in-Chief at Knopf] wasn’t particularly interested and that fell apart after awhile. The idea of an all Indian vegetarian cookbook remained. I had done World Vegetarian and Asian Vegetarian books, but I never dove into Indian vegetarian. And I always wanted to a book that was just Indian vegetarian because there is so much in India.

GFR: As you say, it’s the one great world cuisine that has a long and established vegetarian tradition.

MJ: For over thousands of years.

GFR: How much of the food in Vegetarian India is from a 1,000 years ago, and how much is from yesterday?

MJ: It’s probably all from yesterday. But, in India, everything that’s from yesterday is related to a 1,000 years ago. When your mother talks to you and says, eat this with that spice, it’s from that whole Ayurvedic way of thinking that goes back to eternity. Balancing meals, you eat this with that and put this vegetable together with this vegetable, and then you add a yoghurt.

GFR: Is that relatively universal, or does that vary from house to house?

MJ: It’s relatively universal, within India.

GFR: I ask because last time we spoke we discussed the variance of recipes from village to village, and house to house.

MJ: That varies, but combining foods, so the nutrition is complete is different. That is universal because the meals are set-up to feed you correctly.

GFR: At our website, Good Food Revolution, we’re very wary about anyone who makes health claims related to food.

MJ: That’s why I don’t make health claims. All I say is this is traditionally done this way. But I have no health claims to make, really.

GFR: I agree, you don’t. But, I have noticed that when credible sources do come up with health claims for foods, they are for often traditional Indian ones like turmeric or cumin.

MJ: I have a turmeric pill every day, but I don’t go around announcing it, because then people might think I am quite kooky. [Laughs.]

GFR: You don’t have a line of turmeric pills you’re trying to sell?

MJ: No, I don’t sell it, I just eat it. It’s a known anti-inflammatory.

GFR: So, between the traditions and Western science, whatever that means, there does seem to be something to it all?

MJ: Yeah, but I can’t prove anything and I am not in that business. I am in the tradition business, though, which is that you cook things in certain ways. Turmeric is, for example, always put on fish. Before you do anything, you put on salt and turmeric. The salt bring out the liquids for cooking and the turmeric is an antiseptic and an anti-inflammatory… plus you add chillies for good measure. So, by this time you’ve got your fish nicely Indianized.

GFR: I’ve led you off topic for Vegetarian India, but that sounds simple and delicious.

MJ: They way that I cook is mostly vegetarian with some fish.

GFR: Do you not eat meat?

MJ: No, I will eat it if it’s offered to me. I will eat everything. But this how we eat, ourselves.

GFR: Hugh Acheson says that one of things about North American food culture is that until fairly recently we didn’t actually know how to cook most vegetables. That’s why we have not always appreciated them. Things like mushy Brussels sprouts.

MJ: Even now, if I go to a restaurant, all I see is meat and a little bit of tiny vegetable. It’s like a garnish, the vegetable here. I don’t like that. I don’t consider that a satisfactory meal, actually. I am used to, and my body is used to, a small piece of meat and more variety and quantity of vegetable.

GFR: This seems to be the gastronomic destination that more and more people are coming to: easy on the meat, lots of vegetables and some grains.

MJ: And dahl! Beans, I call them.

For this book, I was very interested to see how different groups of people ate, so I followed them around: jewellers, shoe sellers, just to see what their diets were. How they ate, whether the main meal was breakfast or lunch or dinner or what. And what they would eat for that main meal. The jeweller, for instance, came home for lunch and that was his main meal of the day. His whole family was there, except his father who came and took over the shop. And then I was in the chilli farms in South India, where the chillies were being harvested. The chilli picking women are often migrants and I wanted to know what they ate. I had one of them open up her lunchbox. In it was rice and a kind of salsa made with tomatoes and chillies and garlic. I thought, it’s so like an Italian poor person who is eating a pasta with olive oil and garlic and chilli. It’s very basic. A grain to feed the body and a little flavouring to give it some colour. It’s very similar everywhere.

GFR: The difference being we’re not spending all day labouring in the fields, so maybe we need more vegetables, less grain?

MJ: Exactly.

GFR: A standard book journalist question is, who is this book for?

MJ: Anyone who wants to pick it up! I think it’s for anyone who’s interested. Who is it for? I don’t know, I just write these things! I don’t worry about who they’re for. That’s your job! [Laughs.] I suppose it’s for anyone who is interested in Indian food, healthy eating, vegetables and who are interested in flavour and really yummy foods.

Malcolm Jolley is a founding editor of Good Food Revolution and Executive Director of Good Food Media, the company that publishes it. Follow him on Twitter or Facebook.

Malcolm Jolley is a founding editor of Good Food Revolution and Executive Director of Good Food Media, the company that publishes it. Follow him on Twitter or Facebook.