Malcolm Jolley gets deep into the Alto Adige’s signature red grape…

Long cultivar Lagrein grapes at the farm of Dr. Urban von Klebelsberg in Gries.

I traveled to Bolzano as a guest of Wein Südtirol / Vini Alto Adige recently to attend this year’s Wine Summit held in the city. Part of the program conference, which included an anteprima tasting, was a day of vineyard and winery visits. Delegates were asked to pick an itinerary based on one of the grapes customarily grown in the Alto Adige and I had put down Lagrein because I was familiar enough with it to know that it’s not typically grown anywhere else and makes some good fruity and peppery reds that come through our market and a good price to quality ration. But other than that, I didn’t know much. Here’s some of what I learned.

A view of the city of Bolzano from Griesbauerhof in the St. Magdalena Classico DOC.

First of all Bolzano, or Bozen, is very much a wine city, in so far there is a quite a lot of wine grown within its limits. To the east of the city centre is the St. Magdalener Classico DOC, where I went with my Lagrein minibus group to Weingut Griesbauerhof. There we were hosted in the vineyards and winery by the Mumelter family. Michael Mumelter gave us a tour of the Lagrein vineyards on the slopes that descend from the winery and provide a stunning view to the west of the city of Bolzano. Behind us to the east were steeper slopes rising up planted with St. Magdalena vines, also known as Vernatch and now more commonly in North America by its Italian name Schiava. This, Michael Mumelter explained to us is the way in Südtirol. Where red grapes are grown, and especially in Bolazano, the low lying vineyards are planted with Lagrein, and the higher and steeper ones with Schiava. At Griesbauerhof the Lagrein vines were planted ‘traditionally’ pergola and the fruit hung heavy in early September. This was our first stop, and destined to be our last for a comprehensive tasting and lunch under the vines, but the Mumelter famil, which includes Michael’s oenologist brother Lukas and parents Georg and Margareth, gave us a treat before we left: a glass of their crisp and fruity sparkling Lagrein sipped on their terrace overlooking the roofs and spires of the town.

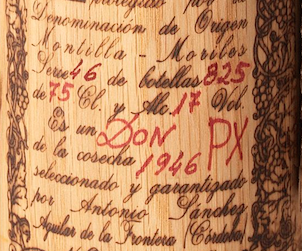

We left St. Magdalena and crossed Bolzano to head for Gries, a well to do looking suburb, to visit the farm of Dr. Urban von Klebelsberg who grows Lagrein for the Cantina Bolzano, or Kellerei Bozen. The Kellerei is the region’s biggest, and best known, co-operative. I am certain the first Lagrein I tasted was from the Kellerei since their wines often come through the Vintages program in Ontario and offer tremendous value for wines in the $20 range. They make all kinds of levels of wine and Dr. von Klebelsberg’s grapes go into their fancier Riserva line. Or so explained the Kellerei’s chief winemaker Stephan Filippi who joined us at the vineyard. It turns out that Urban von Klebelsberg is a winemaker of renown in his own right, as I learned later when Googled him. He makes wine at Italy’s northernmost winery, the Abbazia di Novacella in the Valle Isarco near Austria. His property in town was relatively low lying on valley floor near the Talvera River, a tributary of the Adige. Surrounding it were hills planted with Schiava.

Dr. Urban von Klebelsberg in his Lagrein vineyard.

The vineyard was planted vertically rather than in pergola. We asked Filippi why and he explained that the ‘tradition’ of pergola was only about 150 years old and was designed to increase yield. In sites like von Klebelsberg’s on a valley floor, he thought vertical training was much better to resist disease pressure and produce less, but more concentrated fruit. The climate in the valleys that house Bolzano is decidedly Mediterranean and warm. The Dolomite Alps that surround it provide shelter and act a bit like a solar oven. Filippi explained that there are days of the year that Bolzano is the hottest city in Italy, and it’s for this reason that Lagrein thrives here and can mature into an intense red wine grape.

The monastery and vineyards of Muri-Gries.

Kathrin Werth works for the monks at Muri-Gries, a monastery that dates back to the 11th century. Muri-Gries is in the middle of the Gries suburb and behind the walls we could hear the sounds of city streets. Here Lagrein is also grown on a vertical training in a walled in clos on the Talvera River flats. As Werth guided us around the cellars and cloisters of the old monastery she told us something I didn’t know. Until the 1990’s at Muri-Gries and throughout the Alto Adige at least 80% of Lagrein production was reserved for rosé. The shift to dry table wine is a relatively new development and is in part possible because of the warmer temperatures associated with climate change. So, even though Lagrein is an ancient indigenous grape from the Alto Adige, with references to it dating back to the 12th century, the way we enjoy it now is more or less new. As I absorbed this information it struck me that there was only one course of action to take for the remainder of the day: taste some Lagrein wine. And that’s exactly what we set out to do on our return to Griesbauerhof to meet some of the region’s top producers and try their wines. Stay tuned…