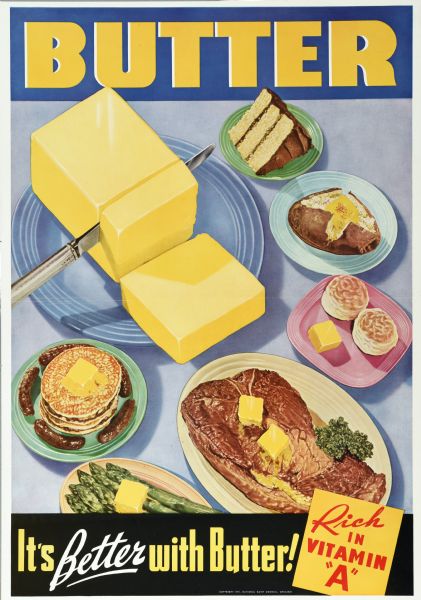

It’s Better with Butter

Eat.Play. Rove. with Lorette C. Luzajic

Dr. Seuss’s Butter Battle Book is not nearly as popular or famous as Green Eggs and Ham, or How the Grinch Stole Christmas. It was released in 1984 as protest for the Cold War, a rhyming satirical attack on how world governments court annihilation over trivia, in this case what side the bread should be buttered on. Though Seuss’s message books, such as the ecology story The Lorax, as well as his playful rhymes about nothing, were long championed by left and right and in between, this one was more of a fizzler than a sizzler.

Perhaps the book was too simplistic in its analysis of nuclear threat. More likely, the good doctor’s storytelling reign had simply run its course.

The irony was what The Butter Battle Book was not about, however. The butter battles.

There were a few.

Who knew? The first student protest in American history was a food fight. The great Butter Rebellion of 1766 at Harvard University was a student uprising against rancid foodstuffs on campus. Forget “Give me liberty or give me death!” Protestors allegedly declared, “Behold, our butter stinketh!” It is debatable if school cafeteria food has improved in the four centuries since then.

Another butter war was raging soon after. In the 1880s, the USA imposed steep taxes on margarine, ostensibly to support farmers selling the more expensive butter. Canada banned the substitute outright, until 1949.

These were major issues for dairy farmers, but also for the Newfoundland Butter Company, which made “table butter.” Table butter was the palatable term given to our east coast oleomargarine, made using the oils of the fishing industry- whale, seal, and fish oils. In 1949, Newfoundland became the last province to join the confederation we call Canada. That this was the same year as the legalization of margarine was no coincidence. Fish margarine was an important industry to Newfoundland and the coastal population.

Was whale blubber butter the Canadian cow’s only competitor? Fat chance.

To most of us, margarine is not seafood. We think of it as the plant-based, all-natural, heart healthy, animal-free spread. This is all marketing mumbo jumbo, knit from unholy alliances between big businesses, governments, scientists, and the corporate and medical associations touting the party lines. The biggest butter battle of all continues to this day: plant-based versus animal-based fat wars are sometimes expressed as saturated versus unsaturated fat debates. Though this is sold to us as a health and justice issue, behind the scenes it was all about processed plant profits. Chemical, industrial un-food marketed as natural has high profit margins. Olive oil is a plant oil- but hydrogenated soy or cottonseed oils meant for candles are unnatural, industrial un-foods.

What is butter? Butter is a semi-solid emulsion of dairy fat that stays firm at room temperature and hardens in the cold. Most western cultures think of butter as cow fat, but it is historically made with goat, sheep, buffalo, yak and camel cream, too.

What we think of as a guilty pleasure has been an essential part of the human diet for thousands of years. Butter was long a major food group. Butter facilitates absorption of fat-soluble vitamins, contains essential fatty acids, contains cholesterol (a vital nutrient we’ve been brainwashed to fear) and a wallop of calories. While few of us today require easy access to more calories, throughout history the struggle was getting enough.

Olive fat was sacred and beloved, too, but margarine was not a contender because it didn’t exist. Margarine was invented in France in the 1860s during a butter shortage. It was made of beef fat. Margarine as we know it- filled with those dreamy healthy natural plant-based fats- came about in the 1930s. It started in the 10s, when cottonseed oils were repurposed from light fuel to replace lard and sold as better tasting and healthy. Then the same thing happened with margarine. To make a complicated and long story short, the advent of electricity had decimated the candle and lantern industries. In the post-war economy, with food and fat rations, and with the second world war percolating, the cottonseed oil, coal and paraffin wax industries switched gears and started manufacturing “natural” and “healthy” alternatives to butter.

The long catastrophe of hydrogenated oils continues to unfold. Sleazy and corrupt corporate-government alliances ganged up on frightened and deprived consumers, offering a joint fear-mongering and morality play. For the first time in human history, animal fats were blamed for diseases. If self-interest didn’t move someone, cruelty would. Most caring citizens had concerns about the reprehensible business of factory farmed animals, so they were easy to persuade.

With media propaganda doing the dirty work to sell fake food as healthy and natural, the unfood industry was born. Processed foods served a dual purpose- to provide shelf stable products that could be managed in the working schedules of modernity, and to make massive profits.

Though we were told that animal fat caused obesity, heart disease, and cancer, and that this was solid science, historically these were rare conditions, and since we switched to processed foods, diabetes and other metabolic illnesses are epidemic.

No one in their right mind would buy tasteless coal butter, chew on chemicals, or choose boxes of powdered egg-like chemicals for their families, of course, unless they believed it was the right thing to do- an ethical choice, or a healthy one. Millennia of traditional wisdom when it comes to hunting, eating, cooking, and farming had to be dismantled.

Bidding bye-bye to butter was a tough sell. Lore about the invention of butter were integral to many cultures. From Europe to the mountainous regions of Asia to the deserts of Arabia, stories abounded on how butter came about. And it is entirely possible that these cultures made butter independently of the others. Most of the memories went something like this: so and so’s great great great great grandfather was taking some yak milk to the village and discovered it had separated from the jostling of the journey. Voila, butter was born!

In Elaine Khosrova’s 2016 book, Butter: a Rich History, she claims butter was first made in Africa ten thousand years ago, a happy accident discovered after a journey churned some cream. Food historian Harold McGee says the same thing happened at the same time, but in Iraq or Iran. Wherever there is a milk producing animal, a similar story crops up. Indians have been making ghee- which is basically “butter oil” as it discards everything but the fat!- since prehistory. (In South America, llama and alpaca butter and cheese exists, but it is rare because these animals do not produce much milk.)

In various cultures sweeping across Asia, Europe, Africa, and North America, butter was prized and revered, not maligned. Butter was slathered on everything, because it was a key to survival, health, and longevity. Butter is full of healthful ingredients. Some are so rare as to be magical.

Yes, it has saturated fat and cholesterol, and these are precious, vital nutrients (long story for another time.) Butter made by animals that roam and graze naturally contains Vitamin K2, a rare nutrient that has nourished our brains, arteries, and glands for millennia. Butter has prize fatty acids, including lauric acid, conjugated linoleic acid, and the often maligned arachidonic acid. Lauric acid is so rare it is only found in breast milk, coconut oil, and butter. It is incredible for immunity, and it is anti-viral and anti-fungal, and anti-inflammatory. CLA is vital for building muscle, and killing cancer cells. Arachidonic acid builds cells, including brain cells.

Vitamin A is an important vitamin and hard to get. You’ll see sweet potatoes and leafy greens on every list for Vitamin A, but this is not the whole truth. At our house, we make chard, collards, and the whole garden gamut regularly. But no plants contain Vitamin A! They contain beta-carotene, which the body can sometimes use to manufacture Vitamin A. This is not quite the same thing.

You need fat in order to do that, first of all- but not all bodies do it well. Beta-carotene is not nearly as bioavailable as animal retinol. And it is rare- some fatty fish, some cheese, eggs, and grass fed butter are all we’ve got. Liver is the best source. Vitamin A is a super warrior for killing off cancer cells, preventing weak eyes and blindness, and is an immune system superstar. But synthetic versions are toxic, so popping pills doesn’t help.

Vitamin K2 is actually a whole constellation, like the B Complex vitamins, rather than a single entity. We need it for healthy blood, flexible arteries, for calcium distribution to our bones and teeth (and out of other tissues, such as calcification in veins, pineal gland, or in stones in our kidneys!) It is very important for heart health.

The best butter you can use is the stuff of the centuries- raw, cultured, and grass fed. This butter is teaming with probiotics, enzymes, fatty acids, and Vitamin D, A and K2. Unfortunately, raw dairy is prohibited today. Grass fed butter is much more expensive than regular, but worth every penny.

Traditional cultures have long valued “grass fed” butter so much that it is literally the food of the gods. In Hindu India, butter is holy, as is the cow. Ghee is known as “liquid gold” or the “sacred fat.” It is used throughout Hindu practices, such as pouring into sacred fires, and lighting lamps for Diwali. Not only is it an offering to the gods, it is the source of divine life itself: In Hindu mythology, Prajapati, the god of offspring, made ghee by rubbing his hands together. When he poured the ghee into the fire, his children were created.

Krishna- Personification of Love and Benevolence ! Photo by Shruti (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Lord Krishna loved butter so much that stories abound of an impish young Krishna stealing butter, even earning the title “the butter thief.” There are countless paintings and figurines depicting Lord Krishna stealing or eating butter, or watching his mother churn butter.

The ultra high fat, shelf stable butter oil ghee was never feared for its fat, but instead formed the backbone of Ayurvedic medicine! It was deemed essential for transporting the benefits of herbs to the body- which is ancient wisdom for modern science, as we know today that we cannot absorb plant nutrients without fat. Ghee increases intelligence, protects against infections and diseases, heals wounds, and aids digestion.

In Ireland, archeologists have excavated “bog butter,” ancient jars of the sticky stuff hidden in swamps, from 400 BC. Some historians believe this was simply to hide food stores from marauding enemies. But others believe these were pagan offerings to the gods.

The goddess Inanna in ancient Sumer also received butter offerings, and tablets of cuneiform writing have been found depicting ancient butter making practices.

Yak butter has long been used in China, Nepal, Mongolia, Pakistan, India, Nepal, and Tibet for food- and for tea. In recent years, you’ve heard the concept of bulletproof coffee, or butter coffee, which calls for butter instead of cream in the daily joe. This concept has ancient roots. Yak butter tea is so prized for nourishment that Tibetan monks drink sixty cups a day!

Monk in Tashilhunpo Pouring Butter Tea Antoine Taveneaux, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Tibetans also have a yak butter carving tradition, with monks and nuns making elaborate butter sculptures called torma as monastery and festival offerings since the 1400s. The butter art symbolizes the light of wisdom and the impermanence of everything. Butter fueled lanterns are part of the New Year’s Butter Lamp Festival. Jamyang Khedrup, a Tibetan Buddhist monk and also my friend, explained to me, “The offering of butter lamps is very important. Offering lamps to the Buddha is said to…bring forth the light of wisdom, which clears away the darkness of ignorance.”

Sculpture made of yak butter at Taersi lamasery in Qinghai. photo by Tim Zachernuk. (CC BY-NC 2.0)

In northern European cultures, butter was considered vital to the family table and an important commodity, as well. The late medieval years and the Reformation changes to culture were peak years for the witch craze. Since women did most of the milking and the butter churning, naturally there were suspicions that they were actually the “devil’s milkmaids.” The phrase “churning butter with the devil” came into use, too. Women with special success at making butter must have had help from Satan on the down low. Throughout Scandinavia, there are old artworks showing demons churning butter or suckling at the cows. Incidentally, the Danish also have a word butter so thick there are toothmarks: tandsmør means “tooth butter.”

Still-Life with Glass, Cheese, Butter and Cake, by Floris van Schooten 17th century

In France, buttery cooking is next to godliness. Butter is the foundation of classic cuisine, both couture and rustic. It is found in pastries like croissants, in French Onion Soup, and on fish. The French eat the most cow butter, per capita, of anyone in the world.

In French cooking, it is also common to make your own butter at home, something you can learn with the whole family locally in Ontario from Black Creek Pioneer Village, online.

You can support Canadian and local farmers, and vote for grass-fed and humane butter with your dollars. St. Brigid’s Creamery makes amazing butter, and pledge “a commitment to the regeneration of our soils, the health of our communities, and animal welfare.”

Another great choice is Savor butter.

You can celebrate the divine gift of butter, including these grass-fed gems of Canada, with the latest TikTok trend for butter boards. This is something like a charcuterie board, with a curated selection of butters, bread, jam, honey, and so on. Or you can just add a generous spoonful to your tomato soup or a fresh loaf of sourdough bread. As the famed American chef, Julia Childs, maintained through all the years of the butter battles, “Everything is better with butter.”

Lorette C. Luzajic

Young Woman Churning Butter, by Jean Francois Millet c. 1851