It’s BBQ Season!

Summer is here, and I’d say it was barbecue season, but one thing my Dad made clear was that BBQ is an all season affair. In the dead of winter, he’d step outside the patio door to turn the meat on the grill.

Most of us prefer outside gatherings in warm weather, but Dad preferred meat cooked on the flames come rain, snow, or shine.

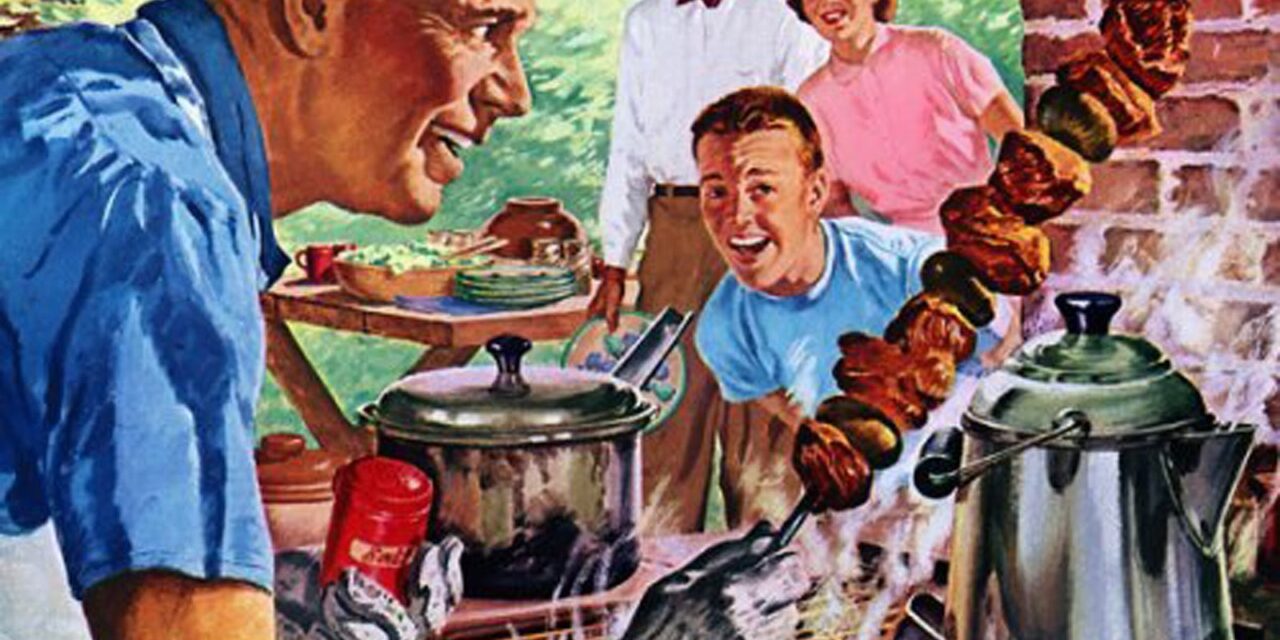

Although the whole barbecue love thing is considered by many a kind of gender stereotype of the suburban but rugged white American male, kind of like the Marlboro Man, it’s really nothing of the sort. Like the chain-smoking Adonis, that imagery was manufactured in the golden age of advertising, coinciding with the appliance revolution that brought the backyard BBQ into postwar homes. Smiling domesticity and convivial neighbourhood picnics ensued.

Dad was the outdoorsy sort, to be sure, passionate about camping and kayaking, and a handyman, too- he built the outdoor kitchen where he grilled winter or spring. But he handed the meat fork over to his daughters often enough, and loved chopping cabbage and slicing carrots and tomatoes, too. He helped wash the dishes afterward, and enjoyed choosing the best wine to pair when planning the meal.

Barbecue, of course, is not just for men, and it is not only American. It has varied and rich traditions of technique and flavour from every corner of the globe. It is the domain of both men and women. The folklore is fraught with both flavour and controversy, but one thing is certain: barbeque is not modern. It’s one of the oldest stories in the book. So old, in fact, that some theorize, quite convincingly, that putting the meat on the flame is how we became human in the first place.

Ancient Greek Grill 6th Century BC Jerónimo Roure Pérez, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

The most basic operating definition for barbecue is “cooking meat.” The word “barbecue,” sometimes spelled “barbeque” and frequently abbreviated to BBQ, is a both a noun and a verb. It’s often used as an adjective, too! It sometimes refers to the flavour, and sometimes to the event, and sometimes to the process, and sometimes to the equipment used. The method varies from home to home and culture to culture, including smoking, open pit roasting, hot stone cooking, flame grilling, hot coal cooking, hot pits dug into the earth, and more. And it gets murkier.

Some say the word comes from the French “de la barbe a la queue”- barbeque- meaning the whole beast, beard to tail. A whole animal spit roast is one of the most ancient ways to cook, after all.

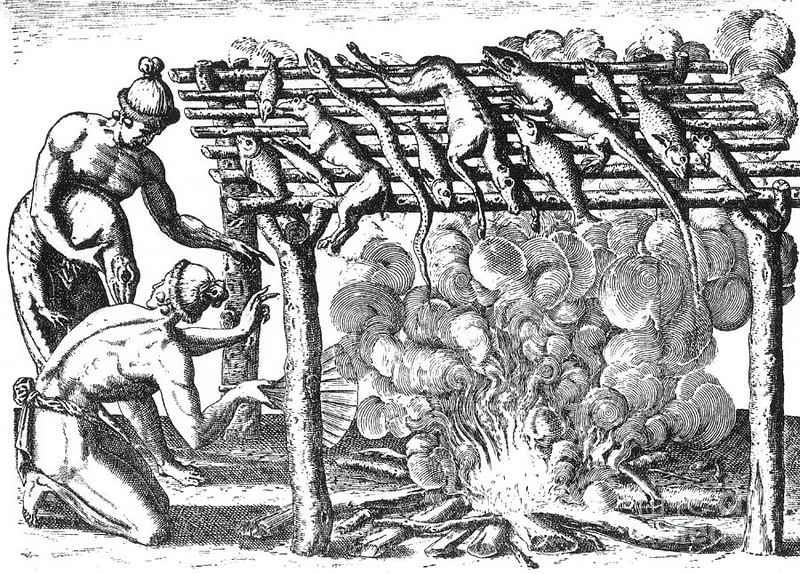

Others say the word comes from “barbacoa,” which was a device with a platform held up by sticks, over an open flame. This was used by various peoples in the Caribbean, to heat water and to cook meat. Spanish explorers and colonists first mentioned it in the early 1500s, and we assume they got it from the word “barabicu” from the Arawak language.

This origin story is loaded with controversy. In 2008, Andrew Warnes argued in his book Savage Barbecue, that barbecue itself- grilling meat- is something Europeans connect with savage or primitive people, and those of us who enjoy our seasoned beasts in the backyard are inadvertently participating in the traditions of slavery.

American BBQ is an extremely diverse tradition with countless regional flavour and method variations. “Southern BBQ” alone can be broken down into endless palate variants and marinating or rubbing techniques. It is absolutely true that during the dark stain of slavery, in the USA as well as in the Caribbean, Brazil, Argentina, and beyond, enslaved Black people were often forced to do the cooking. This included gruelling work over flame pits, with delicious meat that would feed plantation families, lavish parties, and sometimes the slaves and their families (who more often did the cooking but ate only scraps.) Many of the prized methods and flavour profiles of modern BBQ are indeed borrowed from this blight in our history.

In Slave Narratives: A Folk History of Slavery in the United States from interviews with Former Slaves, Volume 14, South Carolina Narratives, Part 3, former slave Wesley Jones spoke of the work he did for the plantation owner.

“… I used to stay up all night cooking and basting the meats with …vinegar, black and red pepper, salt, butter, a little sage, coriander, basil, onion, and garlic. Some folks drop a little sugar in it. On a long pronged stick, I wrapped a soft rag or cotton for a swab, and all night long, I swabbed the meat until it dripped into the fire. The drippings changed the smoke into seasoned fumes that smoked the meat. We turned the meat over and swabbed it that way all night long until it oozed seasoning and was baked all through.”

The vinegar and pepper sauce is one of the Carolina BBQ traditions to this day. Other Carolina recipes like the mustard BBQ sauce trace back to German farming immigrants, but the fact remains that men and women like Wesley Jones literally laboured over hot coals for some of our traditions.

Ancient Americans Cooking, by Jacques Le Moyne 1500s

Another accusation connecting the word “barbecue” with racism is the idea that Europeans viewed indigenous and African people cooking meat as “savage” or “barbaric.” It’s possible indeed that Europeans saw game like lizards, crocodile, and local livestock varieties as strange. Most cultures find unfamiliar eating habits distasteful initially. I recall in high school being considered very adventurous because I dared to try sushi when I visited Vancouver. Now there are thousands of sushi restaurants all over Canada, and raw fish is everyone’s favourite way to get their Omega Threes.

However, it wasn’t just iguanas that repelled the Spaniards. Early records associate these Caribbean barbecue stands with cooking human meat! There are numerous peculiar illustrations showing cannibal cookouts, and diary descriptions to go with it. Associating the cooking methods of the Caribbean and South American people they encountered with cannibalism is also at the root of the concept of the word “barbecue.” Today this is considered colonialist fiction and dismissed as dehumanization.

It was indeed popular for colonizers, tribes, and peoples throughout history to dehumanize other groups by accusing them of cannibalism. To take over land or subjugate people, you just needed to lobby people-eating slander to justify violence or colonization. But not all accounts are false. The practice was quite commonplace in warfare, religious ritual such as human sacrifice, magical beliefs, and survival cooking, throughout history and throughout the continents. It was not a practice specific to any race or culture. Cannibalism was routine among prehistoric people, and although rare in the modern world, it happens still. The reasons of old are the same now- sometimes it is survival, such as famine or being stranded remotely. Sometimes it is ritualistic, and accompanies magical beliefs. Sometimes it is violence and sadism, such as brutal warfare tactics or a deranged serial killer. And sometimes it is pragmatic- why waste good protein?

Cannibals in Brazil, Theodore de Bry 1562

Whether the barbacoa set up was used for this purpose or not is shrouded in the mists of time, and prejudice and politeness alike. What’s definitely true is that BBQ is not an American tradition, and it is about two million years older than the Spanish arrival on Caribbean and South American shores.

In the 2009 book Catching Fire, Harvard anthropology professor Richard Wrangham explored “how cooking made us human.” While it is a logical inference that raw food for humans and animals is more natural, cooked food is more accessible to the body and creates fewer demands on the digestive system and on our energy. Once we put flame to our game, our brains grew larger and we began to spend more time developing activities and culture other than mere survival. Curiously enough, studies show that the animal kingdom, including primates, usually have a preference for cooked food when given the choice!

Some anthropologists still date the advent of cooking at 300 thousand years ago, but more and more are pushing that date back to align with Wrangham’s hypothesis as we continue to study the evidence.

And everywhere we went, we lit fires and flame broiled, grilled, and smoked our prey with whatever spices and flavours we had on hand. Fish, antelope, moose, eels, giraffe, crocodile, rodents, sprinkled or stuffed or rubbed with local leaves and pods.

Night Banquet, by Seong Hyeop 18th century, The Picture Book of Genre Paintings

When you’re in North York, with family around a table grill at a Korean BBQ restaurant, you’re participating in a ritual that is 2500 years old! The meat, the tasty side veggie dishes, and the beer are all part and parcel of an ancient culture of gathering. The nomadic Maek people of the Goguryeo era would rest together after a long day and eat maekjeok, which later became bulgogi- “fire meat.” The Buddhist influence in Korea added vegetable dishes to the meal. The booze was reward and relaxation for the day’s work.

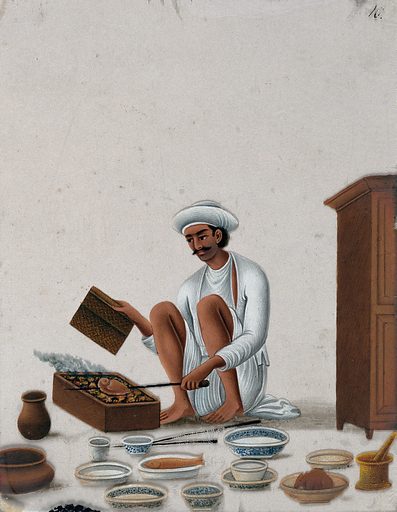

If you’re a fan of spicy tandoori chicken, you may conclude that “tandoori” refers to the bright red sauce. The tandoor is actually the oven. The wildly popular red chicken is a relatively new recipe from last century, but the portable wood fired clay oven is over four thousand years old. It was traditionally used to bake bread in India, and spread through China and the Middle East, and is used to cook meat, vegetables, bread, and stews.

Indian Barbecue, goauche on mica, artist not known India 1800s

Indigenous Canadians frequently placed their fish and game over the fire, but not too close, sometimes on cedar planks which impart a delicious flavour complexity to the catch. Traditionally prepared cedar salmon BBQ is a widely enjoyed west coast Canadian delicacy even today, frequently sought by visitors.

Kebab Grill hildgrim, CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

The kebab is everywhere today, from Toronto cafes to food trucks in Scotland and Italy. The shish kebab has origins in Turkey, when soldiers would grill meat on sticks during their invasion of Asia Minor in the 11th century. The word shishkebob simply means “roasted meat on skewers.” The kebab went everywhere because it was a natural solution for nomadic peoples to easily prepare and carry. Each group added their preferred spices and sometimes, breads alongside or to wrap. In Malaysia and Thailand, you have satay, and in Greece, souvlaki, and in Toronto and London, you have all of the above when you need a late night snack or are meeting up with friends for a delicious lunch.

In Peru, Ecuador, and Bolivia, you can enjoy cuy asado, or roasted guinea pig, from outdoor BBQ vendors to fine dining. This regional Andean delicacy is from the cuisine of the Incas, tracing back to the 1100s. Cuy is roasted and served whole.

Cuy Asado Ministerio de Turismo Ecuador, CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Pollo a la Brasa is Peru’s iconic bbq chicken. The bird is marinated whole in garlic, cilantro, lime, ají amarillo (Peru’s famous yellow peppers), and huacatay, an aromatic herb native to the Andes. Most recipes also include soy sauce, a fusion of flavours from Chinese Peruvians, whose ancestors came as cheap labour for cotton and sugar in the 1800s.

Portugal is also famous for BBQ chicken. The marinade or rub always includes the peri peri pepper, sometimes called the bird’s eye pepper.

While the portable or single family sizes of the modern barbecue today make us associate BBQ with chickens, slices of meat, or skewers like kebab, the original BBQ is just a fire pit, often massive and communal, making the roasting of a whole animal commonplace historically. Whole pig roasts are beloved from Serbia to Puerto Rico. Whole goat barbecues hail from Vietnam to North Africa. But even the largest game can be cooked whole over an open fire.

Camel is an ancient food tradition in many countries, including Somalia, Libya, Sudan, Egypt, and Kazakhstan. The camel is a massive animal and can feed a whole village or guests at a wedding celebration or feast. One of the oldest camel cookouts we know of was from ancient Persia. Accounts of the feast of King Darius from 485 BC include roast camel, along with gazelle, zebra, oxen and geese. Today it is more common to cook steaks and stews, but there are still occasions for whole camel cooking. The Ercan Steakhouse in Istanbul has a massive industrial smoker specifically for whole beast camel BBQ.

Cooking Camel Meat on Hot Stones in Dhofar Scott Edmunds, CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

We have barely tasted the global story of BBQ. We didn’t even make it to Mexico or Texas for cabeza- cow’s head barbecue.

With hundreds of thousands of years in thousands of cultures, we have not even cracked the surface. There is one man who is trying to explore every nook and cranny of the world’s history of barbecue. Steven Raichlen wrote the book on barbecue- the Barbecue Bible. Or books, that is- there are also Planet Barbecue, How to Grill, BBQ USA, How to Grill Vegetables, the Brisket Chronicles, and more. Steven hosts BBQ University as well as BBQ TV. He offers thousands of recipes from every region of the world, smokelore galore, and countless resources on methods and marinades.

Another resource for all things BBQ is Ontario’s very own Danielle Bennett, better known Diva Q. She has been mastering the grill for over 15 years, travelling the world, and blogging, filming, and writing in addition to grilling. She is considered one of the most influential BBQ competitors in the world, and is frequently a judge at international BBQ competitions.

Perhaps the best way to proceed is to head outside tonight with some meat, fish, spice rubs, and veggies, and grill up a feast of your own. Call your neighbours and friends over and make it a party before summer disappears.

Fresco detail, BBQ Picnic, Trento’s Buonconsiglio Castle, Italy 1400