For over a decade or so I have observed that as a culture we are becoming less and less attached to the earth that supports us with each passing day, and indeed it was co-founder Malcolm Jolley’s and my own mutual concerns about this that led to the founding of Good Food Revolution way back in 2009/2010.

Today, when we get hungry for protein, most run to the supermarket and pick up a pack of shrink-wrapped meat, seldom giving a second thought as to how that meat got to the grocery shelf. And so, with a view to getting closer to the source of my food than most would be comfortable with, I decided in the fall of 2016 (mere days after the US election – no coincidence there) to learn how to hunt.

Running in parallel to my new found interest (read: midlife crisis) came a related passion for self-sufficiency that upon occasion flirted with the concept of survivalism. Being a voracious information sponge, I gorged upon mountains of books and websites, and in my deep-dives I read over and over again that if the world did really fall apart and one had to live off the land, it wouldn’t be big game that one would be surviving upon, it would be the smaller critters: rabbit, hare, squirrel… and in the case of one of these pieces, the lowly frog, but for the most part it would actually be edible plants.

Which brings me to Autumn Olives, a reasonably recent discovery for me. It’s testament to my caution with any new wild food that it has taken me four years to get around to exploring the three Autumn Olive bushes that grow along the side of our driveway. It appears that my acute OCD reigns in a lot of my “riskier” behaviour, and for this I am truly thankful.

The Autumn Olive (Elaeagnus umbellata) is today viewed as an extremely resilient invasive species, having been brought into North America from Asia as an ornamental plant in the 1800s and then planted widely from 1950 onwards by the US Soil Conservation Service to help deal with soil erosion. It spread rapidly, outcompeting and displacing native plants, and is now found across much of Eastern Canada and the US, with some sparse distribution on the West Coast.

The Nature Conservancy Council of Canada advises that it should be rooted out wherever possible and gives advice on how to do this through the use of herbicides, as simply pulling or burning the plant can simply serve to spread it even further.

All of this aside, it’s a fascinating plant and quite a beautiful one too, particularly the berries. As one of the few non-leguminous nitrogen- fixing plants, it can flourish on even the poorest of nutrient stripped soils. Its root nodules house bacteria in the genus Frankia, allowing for extremely efficient biological nitrogen fixation.

Its proliferation across a healthy chunk of the continent is explained simply: one single plant can easily produce upwards of 200,000 seeds, and these are readily consumed and spread through birds and animals ingesting the delicious fruit and dispersing the seeds through their feaces. Interesting enough, the seeds of the Autumn Olive won’t germinate unless they have been through a creature’s intestinal tract.

It can grow from two to six metres tall and can form quite dense thickets if allowed to. The elliptical leaves are grey/green with a silvery and scaley underside that can give the bush a shimmering look in the wind. The ovoid berries turn orange and then almost cherry red (with utterly gorgeous silver-flecked skin) in the late fall, and this is when they are at their most delightful.

An unripe berry will be almost inedible, while a ripe example will be rather sweet, but with a marked acidity and astringency. The seeds are large and leathery, grooved from end to pointed end, and quite chewy if consumed raw.

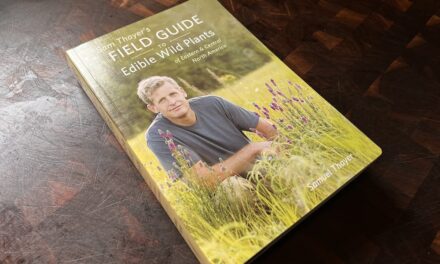

I had read in Sam Thayer’s new Field Guide to Edible Plants (I’ll be reviewing it nest week) that berries can be highly variable from plant to plant, and he wasn’t kidding! The different ripeness levels, and hence flavour profiles, across the three bushes in our driveway were quite astonishing.

They are incredibly easy to harvest, as one simply needs to take a container, hold it under a berry-laden branch, and then run one’s hand gently along the branch to release the fruit. They are also a lot easier to clean than the rowan berries I have spoken of previously, as adding water to the container brings most of the leaves, bugs, and other detritus to the surface for easy removal. It doesn’t take too long to pull off any of the little stems that may still be attached to the berries.

The berries are a good source of vitamins C and E, as well as being incredibly rich in the anti-oxidant Lycopene, a bright red organic pigment known as a non-provitamin A cartenoid. Lycopene is found in all manner of fruits and vegetables and is responsible for the red to pink colours seen in tomatoes, pink grapefruit, blood orange, and the like. Ounce for ounce, the typical Autumn Olive berry is up to 17 times higher in lycopene than the typical raw tomato.

While research is ongoing, Lycopene may also promote good oral health, bone health, and blood pressure. Some studies have found connections between the intake of Lycopene and cancer prevention, in particular for bone, lung, and prostate cancers.

So, how does one consume them?

Well, I do enjoy them raw, and a handful would make a most welcome addition to a bowl of granola and/or yogurt. Saying that, they are not for everyone: Our nine-year-old son was sharing some with his buddies, merrily munching down on them while his pals grimaced at the berries’ tartness. Personally, I find them absolutely exquisite.

My first foray into preparing Autumn Olives was a simple juice; the recipe courtesy of Edible Wild Foods. It’s basically just two cups of washed berries, a few teaspoons of lemon juice, and a bit of honey or maple syrup to balance out the acidity. Whizz in a blender, and you will have a vibrantly red fruit drink. It’s important to give it quite a serious whizz, as those leathery seeds need to be given quite a workover, and even then one may find oneself picking bits of seeds from one’s teeth afterwards. I found it easier to simply swallow all the seed bits as a bit of fibre never hurt anyone, did it?

Next up, I tried making some Autumn Olive cookies, the recipe once again from Edible Wild Foods. These were a huge hit with my immediate family, although a little less so with our son’s friends (and mother).

Our son adored these so much that he is eager to make a few more batches before the season ends. The baking of the berries makes the large seeds almost nutty in flavour, and the berries seem to explode in the mouth, much like enormous, juicy raspberry pips.

In speaking with Ben Caesar of Fiddlehead Nursery, I’ve learned that with the help of a food mill (I must remember to put that on my Xmas list!) one can process the berries to make jelly or fruit leather, with the berries’ natural pectins helping the fruit juice and pulp to set perfectly. Next year!

I’ve been most impressed with my first exploration into the joys of the Autumn Olive, and very much look forward to having them as a regular component of my annual fall foraging.