Olivia Williams’ book Gin Glorious Gin: How Mother’s Ruin Became the Spirit of London is an entertaining hybrid of a serious book of 300 years of London social history and an enthusiastic appreciation of this era’s most fashionable liquor. The young author enthusiastically recounts the shock and horror of Britain’s first tsst of binge drinking, then embarks on a gin palace crawl through the ages up to today’s era of cocktail culture and the resurgence of gin in it modern-artisanal form (see London No. 1). I spoke to Williams recently from her home in the British capital to conduct the interview below.

This interview has been edited for clarity and style.

Good Food Revolution: You’re book is a lot fun, and I think it’s a lot of things, including a great history of London from the 17th Century on, but at its core it’s really about this drink we call gin. Is that what you set out to write?

Olivia Williams: Well, I first got into it because I was doing a history degree and I was studying London history and formt he accounts I noticed that gin shops seemed like disreputable but quite fun places to investigate. And when I came to London after my degree, I realized that gin was actually fashionable as I was doing lots of bar reviews and gin kept coming up. So I thought if there was ever a time to do a history book about gin, it’s while people are drinking it. So, I set about putting together about 300 years of history, from the time they first started making gin in London to where we’ve come to now, where gin is a lot more sophisticated and tasty than it was then.

GFR: If whisky belongs to the Scots and Irish, I guess it’s fair to say that gin is England’s drink? But it wasn’t embraced when it arrived, right? I think you wrote a piece for The Economist that said it was the era’s ‘crack cocaine’.

OW: Yeah, it was basically Britain’s first binge drinking epidemic. And it took 60 years before they got it under control in the 1750s. It was a real social crisis. We enjoy gin now in a vaguely responsible way, but when people first started drinking it in big numbers was a really scary time for London because of all the social problems it created; it was so difficult to get it under control. Once the floodgates had been opened, it took decades for [the authorities] to work out how to get people to stop drinking so much gin. I think that’s partly why gin still has a slightly sketchy reputation, because I think culturally people still remember the gin craze as one of the worst and most infamous drinking epidemics that we’ve ever had.

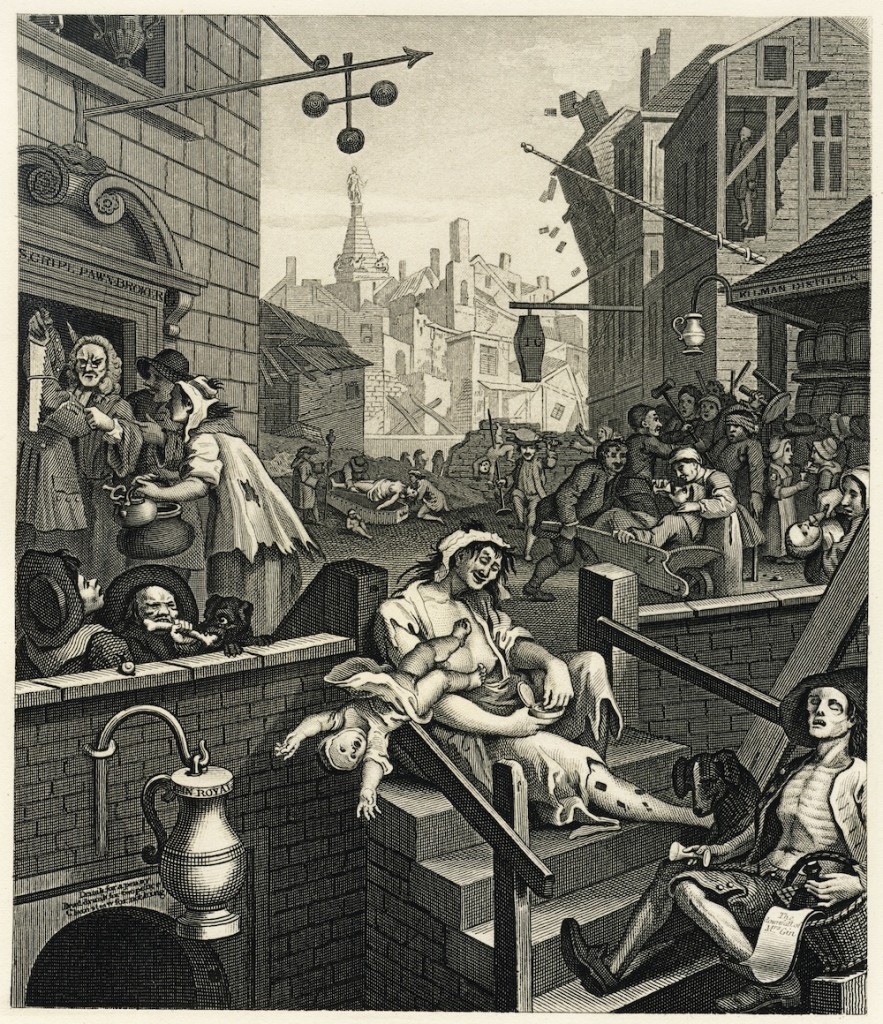

GFR: And of course with Hogarth’s Gin Lane there’s a visual for it.

OW: Yeah, it really helps if you have that one image that really sticks in everyone’s mind, so they can completely understand how dreadful that time was from that fictitious picture. But it doesn’t do much for the post-harm, gentrification of gin, if people who don’t know much about gin only think of that image.

GFR: I want to talk about that gentrification, but first maybe we should be clear that the gin people drank a few hundred years ago is not what we would recognize as gin today, right?

OW: That’s the thing. As well as being culturally very different – the status of gin drinking – the product was very different too. It was made by amateurs. It could be made by anyone who could build a home distilling set-up. The quality of it was extremely poor and very variable. It would often make people very ill, because they didn’t understand how to properly distill and operated by trial and error, and they didn’t want to spend too much on ingredients. People were really taking their chances by drinking it, which has a resonance with 1920s Prohibition in America with people improvising with ingredients and in the way they made it. So, gin was necessarily quite sweet in the 18th century because they were trying to mask what it was actually made of. They also added lots of liquorice. People also would drink gin neat, and it wasn’t until gin became mixed as a long drink that it began to improve its reputation. So, cocktails, and gin and tonics, really helped in the 19th century to pull gin out of the gutter and make you think of it as a pleasant, viable drink, rather than just something to get you drunk.

GFR: One of the chapters in Gin Glorious Gin that I thought was really interesting, is the one about rock star bartenders who came over to London in the 1920s from the States because of Prohibition.

OW: Yes, they were the celebrity chefs of their day. People knew who they were; they would be written up in magazines. They injected their personalities into their drinks. They would play host to the guests who came to stay in their bar’s hotel. And I think the elevation of their status reflected how gin became this very socially acceptable drink. There was a raft of cocktail books, based on the personalities of these bartenders that came out, in the way that a celebrity chef at famous restaurant can bring out a cookbook. It became fashionable to have a signature cocktail, that you always asked for.

GFR: Speaking of which, how much of your book was researched on a bar stool?

OW: [Laughs.] Well, after I did my history degree, I was reviewing bars for a newspaper. So, I did spend a lot of my time in London bars. I was intrigued that gin, which was a drink my parents liked and was so unfashionable for decades that it looked like it was going to die out with the generation that drunk it, was coming back. Again, bartenders were using gin instead of vodka as a base for all these amazing cocktails. And that ’s when I realized that this would be a good time to write about gin.

GFR: Have you become an advocate for the drink? Do people now turn to you to defend gin’s name?

OW: I think that there’s been this explosion of people experimenting with the botanicals that go into gin, so if people think that they don’t like gin, I think they’re just thinking about the traditional ones. They’re very juniper heavy, which not everyone likes. But there are so many other styles: herbal, floral, all sorts of really aromatic gins. There are so many kinds of gin that I think it would be hard for you not to eventually find one you liked.

GFR: And what’s your preference? Are you a Martini drinker? Do you prefer gin and tonics?

OW: I spend a lot of time trying to make Martinis at home. I’m creating a lot of mess! I generally prefer to have one at a professional bar, but I also like to have them at home. I also like the French 75, which is gin and Champagne with lemon. Some people think that gin and Champagne sounds like a weird combination, but it works pretty well. Negronis are very fashionable again, and that’s a great summer drink. There’s another way to make people like gin without them really realizing!

* * *

Follow Olivia Williams’ gin soaked (and other) adventures on Twitter at @tweetingolivia.

Malcolm Jolley is a founding editor of Good Food Revolution and Executive Director of Good Food Media, the company that publishes it. Follow him on Twitter or Facebook.

Malcolm Jolley is a founding editor of Good Food Revolution and Executive Director of Good Food Media, the company that publishes it. Follow him on Twitter or Facebook.