Clotilde Dusoulier became known in North American food circles for her food blog Chocolate and Zucchini. It was one the first to gain a large following a decade ago. Written in English by a young Parisian software engineer (who had worked and lived for a few years in California) with a passion for eating well, Chocolate and Zucchini soon became a cookbook, then Dusouliers wrote another about her life in Paris, and now her third has just been published: The French Market Cookbook.

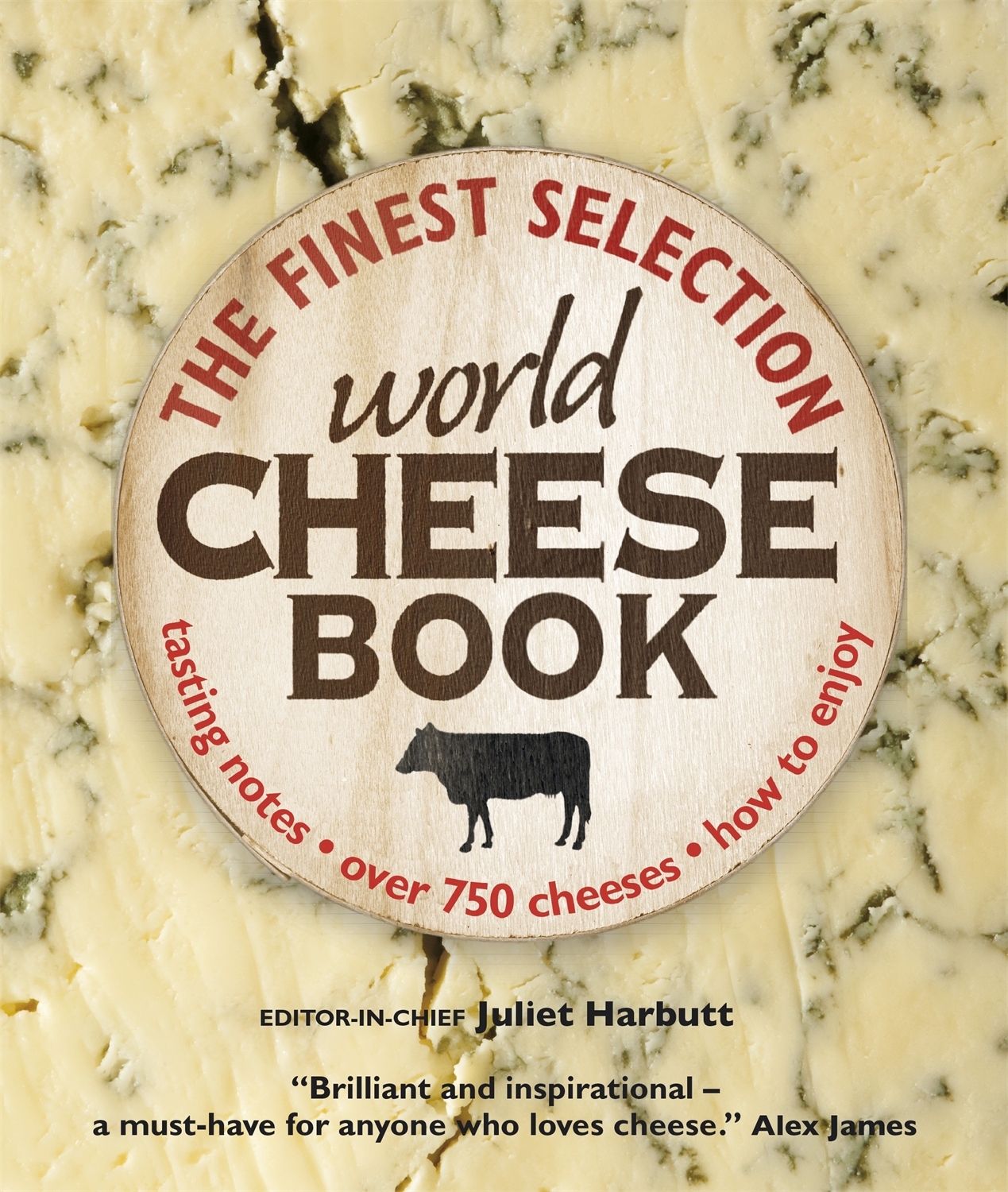

The French Market Cookbook is subtitled ‘Vegetarian Recipes from my Parisian Kitchen’, and reflects Dusoulier’s decision in the last few years to give up eating meat and fish, as well as what she sees as a shift among young French chefs towards plant-based meals.

The book is organized by season and takes its inspiration from the traditional regional cooking of France, as well as the French Maghreb, with Moroccan and Algerian spices and techniques scattered throughout. Praised by American foodist luminaries Dorie Greenspan and Dan Barber and written for a North American audience, The French Market Cookbook seems to be precisely what a young Parisian adherent to Le Fooding might make at home with whatever she picked that day at the market.

I spoke to the thirty-something Dusoulier in Paris, via Skype. We chatted about the cookbook, blogging and her connection to Stratford, Ontario. An edited version of my interview appears below. (I am afraid you’ll have to imagine her very charming French accent in the transcription.)

Good Food Revolution: Why a vegetarian book?

Clotilde Dusoulier: We’ve shifted to only cooking vegetarian dishes at home, and this shift has occurred for reasons of ethics and environmental concerns, but also my personal inclination because I have always been a very vegetable-driven cook. After discussing it with my boyfriend, we came to the realization that we both liked vegetables first and formats, so why bother with the fish and meat?

Clotilde Dusoulier: We’ve shifted to only cooking vegetarian dishes at home, and this shift has occurred for reasons of ethics and environmental concerns, but also my personal inclination because I have always been a very vegetable-driven cook. After discussing it with my boyfriend, we came to the realization that we both liked vegetables first and formats, so why bother with the fish and meat?

So, for the past four or five years, I’ve been eating that way and I realized that I was drawing my recipes from lots of French sources, but I think lots of people who want to start eating less meat and fish don’t think of French cuisine as an inspiration. I wanted to provide a fresh source of inspiration for them that was from a repertoire that’s not often explored with vegetarian goggles on.

Some of the recipes are just personal creations, but many are from researching regional French cuisines and the peasant-style dishes you find, which are often plant ingredients, of course. Also, some recipes come from eating out at restaurants, because the newer generation of Parisian chefs is actually paying a lot of attention now to the kinds of vegetables they use and how they use them. They really want to feature vegetables in a way that’s most amazing, rather than just as an afterthought.

So, all of those sources of inspiration, when they are brought together make-up a collection that provide recipes for weeknight dinners, but also for entertaining – things that are quick, things that are a little more involved. But I always try to present the recipes in a way that are accessible regardless of your level of cooking experience.

GFR: It’s interesting that you mention this new (sort of) wave of restaurateur in Paris who are focussing on vegetables. This seems to be where one finds new flavours. I mean, you can cook a chicken only so many ways, but the palate that this plant focussed cuisine offers seems to be much wider.

CD: It’s true, and I also feel that, perhaps for chefs and home cooks alike, the seasonality (which I really emphasize in the book) provides that sense of excitement that you don’t really get with meat or fish so much. The fact that you really have to suffer through the winter months so that you can really appreciate the arrival of spring and what it brings in its wake. I fell that sense of permanent excitement and novelty is really good to leverage in the kitchen.

I want to stress that, while the recipes are all vegetarian, I designed them so they can find their place in the homes of people who don’t think of themselves as vegetarians. Maybe they want to transition of one evening a week, or every other night without meat. I just think that if we can all make a little effort to eat just a little less meat and fish from where we currently stand, then I hope I giving dishes that make people able to go that route without thinking they are missing something.

GFR: Let’s talk a little bit about Chocolate and Zucchini. I think of you as being one of the first wave of food bloggers. What’s it like now, 10 years after you started blogging? Ho does it compare to being a food blogger when it was just beginning?

CD: It’s true that the world of food blogs is a very different place now than it was 10 years ago when I started. What pops into my head is that I am really happy that there are more of us now, because I remember that when I started there was this kind of sense of… well, I was just slightly worried that people would think I was a little too much into food to devote an entire blog to it. But now, as food bloggers we showed that as a group we can be really normal people – we just can think about the next meal the moment we put down our forks. So, I feel like my people are a lot more visible now than we were 10 years ago.

CD: It’s true that the world of food blogs is a very different place now than it was 10 years ago when I started. What pops into my head is that I am really happy that there are more of us now, because I remember that when I started there was this kind of sense of… well, I was just slightly worried that people would think I was a little too much into food to devote an entire blog to it. But now, as food bloggers we showed that as a group we can be really normal people – we just can think about the next meal the moment we put down our forks. So, I feel like my people are a lot more visible now than we were 10 years ago.

I also think that food blogs can be accredited with accompanying the revival of home cooking. People don’t think of it as a gruesome chore anymore. A lot of people see the joy there is in daily cooking and special occasion cooking, but I feel like it’s the daily cooking that is especially glorified in food blogs. I am happy for that.

GFR: The other thing that I wanted to ask you about was your connection to Stratford and the Stratford Chefs School.

CD: Ah, that was a fantastic experience. I was asked to be the writer-in-residence at the school. This program has been in existence for four or five years and the idea is to give the students to writers. In general their curriculum is really about exposing the students to a great variety of the chef’s craft, and the food writer in residence program allows the students to explore expressing themselves. I really fell strongly that the really successful chefs are the ones who can express the reasoning behind their dishes, describe where their inspiration came from, talk about their cuisine, talk about their vision for their restaurant and write about it. A budding chef needs to work on their voice and on articulating what they’re really about because that is an essential skill if you want your restaurant to become successful.

GFR: In terms of food writing and food literature, you’re bi-cultural, and I think you’re aware of what happens in the English-speaking world as well as in France. Are there big differences?

CD: There are big differences in the world of cookbooks, I feel. In France, the cookbooks that come out are less about the discourse and more about the recipe. I feel that’s regrettable, because recipes are a dime a dozen, but what I really want to know is why. why should I care about this particular recipe and what makes it special. I feel like in recent years the head notes [in French cookbooks] have gotten longer, but we’re still not in North American territory. And that’s probably the reason why my books are published in North America first and then France. I think the North American way is more in tune with my way of sharing recipes.

Malcolm Jolley is a founding editor of Good Food Revolution and Executive Director of Good Food Media, the company that publishes it. Follow him at twitter.com/malcolmjolley.

Malcolm Jolley is a founding editor of Good Food Revolution and Executive Director of Good Food Media, the company that publishes it. Follow him at twitter.com/malcolmjolley.