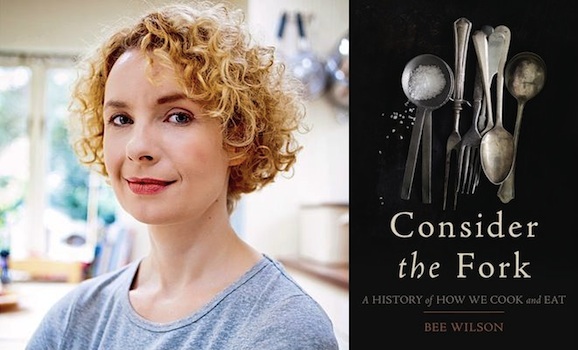

British author and journalist Bee Wilson writes the Kitchen Thinker column for the Telegraph newspaper. The title of her column is an apt description of the foundation of her work, especially her new book, Consider the Fork. Consider the Fork is a smart, but accessible, history and explanation of the more important tools found in the kitchen or the table: forks, knives, pots and pans, refrigerators, sous-vide machines and much else. The book is very much in the tradition of Margaret Visser’s two pioneering (and ahead of their time) food books, Much Depends on Dinner and The Rituals of Dinner. Indeed, Wilson cites Visser in the book and Visser blurbs the book on its back cover, praising Wilson for “conduct[ing] us on a sobering, entertaining and instructive tour.” She’s right.

Food geeks of the Anglosphere rejoice, Consider the Fork is a great read full of fascinating discoveries, provocative theories and amusing asides on the most basic things that help us make our meals. Did the English acquire their taste for roast beef simply because they had the forests to burn long in their hearths, while the tree-disadvantaged Chinese made do with woks over a short, hot fires? And why does one side of the world use knives and forks while the other uses chopsticks? While we’re at it, who knew that Albert Einstein made a brief foray into the refrigerator business in the 1930s? Consider the Fork is one of those books that is at once novel and exciting but also seems retrospectively obvious. Why, I wondered into the second page of it, hadn’t anyone written this book before?

I caught up with Wilson by phone from her home in Cambridge, and asked her how she came up with the idea for the book. She answered, “I started to realize, along with the rest of the food culture, I was very fixated on the ingredients and didn’t think so much about the processes and the techniques and the way that food actually changes over time, even if the ingredients remain the same.”

She began with the fork since, despite its ubiquity, it’s only been on Western tables for a few hundred years (possibly because Cardinal Richelieu). She explained over the phone, “We think we can’t do without forks, and yet our ancestors, when they were eating meals, managed fine using just a sharp knife and occasionally a spoon.” Wilson writes our new found attachment to fork may have even changed the way our teeth are configured in our mouths. It’s one of several loci where she plots our transition to modern, First World, middle class eating, which is to say how we live now.

Consider the Fork is interspersed with anecdotes from Wilson’s family life, amusing tangents and some provocative observations on the Modern Cuisinists. It’s fun to read. But it also contains an important and fundamental lesson for those who care and think about food. As Wilson told GFR, “There’s always another way of doing things in the kitchen. We get into certain habits (I know I do) in such repetitive motion, it’s almost like muscle memory, you reach for the same old tools. But often these things are not the result of pure logic, they’re embedded in our culture, our traditions and the way our mothers did things. And, therefore there are stories behind all of it.”

Malcolm Jolley is a founding editor of Good Food Revolution and Executive Director of Good Food Media, the non-profit organization that publishes GFR. twitter.com/malcolmjolley. Photo: John Gundy.

Malcolm Jolley is a founding editor of Good Food Revolution and Executive Director of Good Food Media, the non-profit organization that publishes GFR. twitter.com/malcolmjolley. Photo: John Gundy.