Lorette C. Luzajic continues her Wine and Art Series with ‘Terrifying Paintings to Accompany You Through the Apocalypse: with Wine Pairings’

Riding With Death, by Jean-Michel Basquiat (1988)

Basquiat fell to the vultures long decades before the 2020 plague, and what may be his last painting tells me he knew the grim reaper was lurking nearby.

The rider is Basquiat’s most sparse painting, stripped of all the busy snippets of graffiti and scrawl and doom and destruction that gave density to everything that made him famous.

The bare bones of this raw prophecy are scary and ugly and show the face Basquiat saw in the mirror. This is surely a rendition of Albert Ryder’s rider, equally as lean and lonely. (Ryder’s night mare has its own curious and macabre saga- worth looking up for the back story.) Basquiat was looking headlong into his own ending at the age of 27, and he knew it.

The artist, who was mentally ill and addicted to heroin, was far gone beyond SOS. This is what he saw coming.

Pair with: Angels Gate Gewurztraminer VQA for the appealing notion of an “Angel’s Gate” rather than the grim rider. This winery offers a heavenly Gewurztraminer that is brimming with aromatic florals, hard candies, and fruit, but still bone dry.

The Triumph of Death, by Pieter Bruegel (1562)

Pieter Bruegel saw all this 500 years before we did, centuries before urban sanitation and electricity and ventilators. The Triumph of Death is, of course, a religious allegory. In those days, everything was, including the crude brutality of disease. As a man of his times, he was completely oblivious to the science of germs and viruses. Illness was always a metaphor of good and evil before those discoveries, and still today: we are urged even now towards misty mind over matter woo by the faithful and the “spiritual but not religious” crowds.

The joke is on us, of course: whether viruses are divine retribution, or the product of negative thinking, or insidious, sinister germs from bats, they’re bigger than us. And in 1562, illness ravaged Europe in wave after wave, leaving rotting corpses to traumatize and infect people at the side of the road.

The irony of this work is that it is housed at the Prado, the reason I went last year to Madrid. Today the great museum is shuddered to visitors, and the hospital floors are littered with desperate civilians clawing at their throats, waiting for a bed, waiting in vain.

Pair with: Marco Abella Clos Abella 2013. You’re only buying time, so don’t be cheap. You may only have days left to enjoy the wonders of the world, of which Spanish wines are part and parcel. Once the stuff was compared to cat piss: don’t believe the tripe. This fine specimen of Carignan and Grenache scores 97 from the Decanter world awards, and boggles the taste buds with blueberries, pencil shavings and anise. Go big with this 90$ winner and have the last laugh at death before she triumphs.

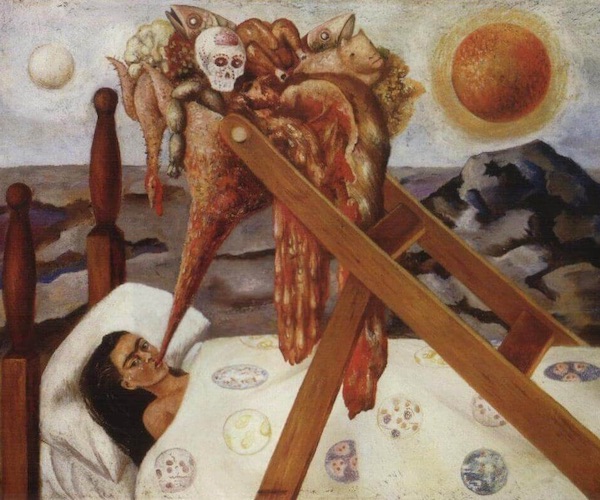

Without Hope, by Frida Kahlo (1945)

Most of Kahlo’s paintings seem on the surface warm and cluttered, the exact same way her country greets you. As they unravel, they become more gory, also fitting with her culture. Mexicans are notoriously colourful in life and in death, and cemeteries and Day of the Dead celebrations in November are raucous and vivid evocations of a ritual none of us will avoid.

But Frida’s work was far more about her reality than about her geography’s collective unconscious. From adolescence through her untimely death at 47, she battled extreme medical trauma. Raped as a young woman by the steel rod of a tram during a crash, her womb was literally pierced, and her hopes as a woman to bear children were erased. Dozens of painful surgeries followed for the rest of her life.

The shelter in place stress we are all experiencing today, she knew intimately, even as her friends romped and roamed wherever they wished without penalty. In Mexico City, I saw her wheelchair, her prosthetic leg, and the easel she’d had installed at her bedside so she could paint while bedridden.

Without Hope is one of several that portray her experience of immobility and her intimate encounter with the grotesque realities of the limitations of the body.

Let this be a sign to our times: one of the world’s most remarkable painters still painted, through countless operations and frequent isolation.

Pair with: L.A. Cetto Cabernet Sauvignon. L.A. Cetto is an OXXO staple in Mexico City, where it’s usually easier, and cheaper, to find tequila or beer. Mexico is the oldest wine producer in the New World- the Spanish couldn’t wait to plant their favourite bevvie- but few locals are converts. Most of the masses stick to their tried and true and the relatively vast wine production in the nation is for ex-pats and exports.

Frida herself was a tequila lover, so it’s perfectly acceptable if you want to slip into the tub with the fruits of the agave instead. I love both tequila and mezcal, but since both demand of me a strict limit of one to two ounces, I still prefer wine, there, or here.

The Cetto is one of the few you’ll see from the region on Ontario shelves, and frankly, it’s fine and that’s about it. But for the purpose at hand, it’s sufficiently moody and bloody, so go for it.

Death and the Woodcutter, by Jean Francois Millet (1859)

Millet was one of Van Gogh’s great influencers, but most of the works seem generic to contemporary eyes. Two of his works are known and loved by the masses: the Gleaners and the Angelus decorate cross-stitch, teapots, and Woolgreen’s framed prints familiar to all of us from our childhood rec rooms.

One of his masterpieces, however, is not so widely recognized. Pity. It’s one of the most poetic and violent depictions we have of the inevitable. It’s the scene from an old fable and poetry, where an unassuming labourer is suddenly assailed, swallowed by the spectre with the thin sceptre.

This is the naked and terrible truth of death: no matter how much you prepare, it will take you unprepared.

Even though we all understand the truth about death and taxes, we are still surprised.

Not one of alive today, even those epidemiologists warning us of just this very thing, were expecting 2020 to play out like this.

Pair with: Felix & Lucie Cabernet-Syrah. Millet was born in Normandy, a northern duchy of France best known for strong cheeses and the apple and pear cider that pair best with them. Though France boasts thousands of vineyards, there are few in this region. You might be lucky enough to encounter a bottle from Arpents du Soleil vines- Acres of the Sun, no less, but right now, that’s not likely. Wash down the harsh dance of Millet’s woodsman with the earthier offerings of the country at large: Felix & Lucie Cabernet-Syrah. It’s dry and chocolatey, and a steal at 15$.

Massacre of the Innocents, by Peter Paul Rubens (1612)

This grisly masterpiece by one of history’s greatest painters is a notch in the Art Gallery of Ontario’s belt. Thanks to the Thomson billionaires of Canada, one of the world’s richest families, for giving their art collection to all of us. One of David’s purchases was this massive, hellish tableau, a gift to the world that set him back 117 million dollars.

As the story goes, upon a time there was an evil tyrant of a king who was so terrified that goodness and light might invade the world in the guise of an infant boy that he slaughtered all the babies he could find.

Four centuries after the paint dried, it is still hard to find a more horrifying and skillful work. If one human figure, or the human hand, are notoriously difficult to render, here there is a roomful of intertwining bodies and dozens of hand and feet in various positions.

Impressive and grand, but it is the blue-gray pallor of the babies that hits everyone in the gut.

Pair with: Gabriëlskloof Elodie The Landscape Series Chenin Blanc 2017. The most famous Dutch wines are South African. To offset the bitter taste in your mouth left by this staggering opus by Rubens, you’ll want to rinse with a Chenin Blanc.

They may have a reputation for being sturdy or utilitarian- how Dutch is that?- but the world’s oldest Chenin Blanc vineyards produce whites that are also expressive, elegant, and fruity.

There are loads of value options you can select, but this splurge just might spark the spirit of survival.

The Face of War, by Salvador Dali (1940)

Dali’s distorted depictions are always strange and unnerving, but The Face of War takes horror to the next level. A kind of totemic shrunken head takes up the expanse of the destitute desert, and the eye sockets and mouth are filled with smaller heads with eyes and mouths filled with skulls. It’s almost an optical illusion, but it is all too real: it gives you PTSD just looking at it. The spindly hair or vines around the face turn out to be serpents.

Dali made himself out to be a larger than life, boisterous, megalomaniac. The persona he crafted was an enigma for survival. He wanted to be weirder than drugs, and spent a great deal of time bellowing about perverse sexual desires or eccentricity. The quiet truth was even stranger: he was really a shy and insular man, extremely sensitive to even the most subtle of stimulations. The epic stuff of war and death tormented him, and he exorcised his imagination on canvas.

Pair with: Tamaral Crianza Ribera del Duero 2015. Get a grip with this gritty, complex, rich indulgence. It could inspire you to write out your own pandemic woes, or come up with a survival plan for the end of the world.

La Miseria, by Cristobal Rojas (1893)

We have been battling the coronavirus foe for fewer than six months, and tuberculosis for quite possibly around ten thousand years. While the mycobacterium responsible for this monster was discovered in the late 19th century, the disease had already been that century’s leading cause for death for decades. Scientists and historians today say TB has been around for 70 thousand years, and the bacteria that causes it for 150 million more.

Venezuelan master Cristobal Rojas’ Misery transcends all millennia forward and back to show the devastation of the disease. It’s a subtle, evocative work that relies on a monochromatic colour scheme centered on brown and gray, like tenebrism and tonalism, for drama. But the emotional punch would still work in dayglo pink- the terror and despair of the couple are palpable. The scene is so real that you are almost afraid to breathe.

And maybe you should be. Tuberculosis feels like an archaic, romantic scourge long past. It isn’t.

It is, to this day, the world’s number one infectious killer. It takes on average four to twelve months to treat with a cocktail of four different antibiotics and lots of bed rest- that is, if you’re curable. The vaccine to date seems only to help children.

There are nearly two billion people today infected, and more than one point five MILLION people die each and every year of TB.

Wuhan who?

Pair with: PKNT Carmenere Reserve. The cure for everything is Carmenere.

And PKNT is one of the greatest value lines at the LCBO.

Wine has been grown in Venezuela since 1515, and it’s fairly decent considering its paucity of popularity globally. But if it was hard to find a bottle before the humanitarian crisis in that country, right now even rum is sparse at the LCBO delivery.

No matter: Chile is always the best that South America has to offer in wine. And Carmenere is its crown jewel. It cures all ills, I’m telling you.

It’s the part throaty, part feathery festival of vine delights, gooey and oaky and peppery. There’s an almost tamarind sweetness at the base of its depths, but you still have to brace for the tannins. Not only is Carmenere the most poetic of all the names, it exceptionally complex yet pleasing on the palate.

It is also miraculous- it rose from the dead, in Chile, 150 years after the phylloxera plague killed it off in France and the rest of Europe. It’s usually the romance of that story that appeals most to me, but today the resurrective properties of the Lazarus grape seem even more poignant.

Lorette C. Luzajic is an award-winning mixed media visual artist from Toronto, Ontario, whose collage paintings are internationally collected. Her art has been featured on a 20 foot billboard in New Orleans, on reality TV, and in ad campaign for Carrera Y Carrera, a Madrid-based luxury jewelry brand. She is a widely published poet and writer, nominated twice each for Best of the Net and the Pushcart literary prizes. She is the editor of The Ekphrastic Review, a journal devoted to writing inspired by art. Her most recent book is Pretty Time Machine: ekphrastic prose poems. Visit her at www.mixedupmedia.ca.

Lorette C. Luzajic is an award-winning mixed media visual artist from Toronto, Ontario, whose collage paintings are internationally collected. Her art has been featured on a 20 foot billboard in New Orleans, on reality TV, and in ad campaign for Carrera Y Carrera, a Madrid-based luxury jewelry brand. She is a widely published poet and writer, nominated twice each for Best of the Net and the Pushcart literary prizes. She is the editor of The Ekphrastic Review, a journal devoted to writing inspired by art. Her most recent book is Pretty Time Machine: ekphrastic prose poems. Visit her at www.mixedupmedia.ca.