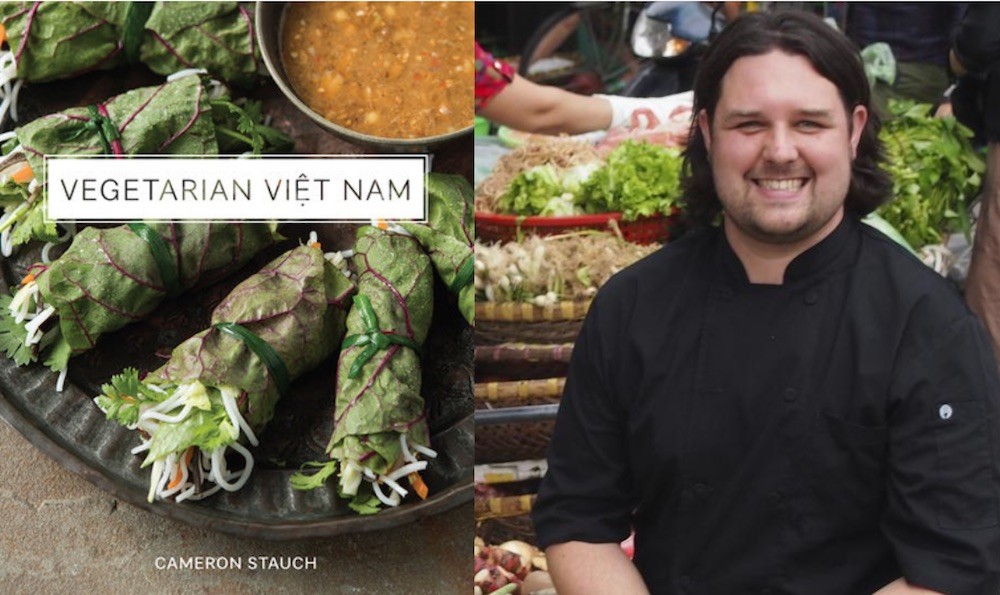

Cameron Stauch is a Canadian chef who married a diplomat. When his wife was posted to Southeast Asia, years ago, he left his job in the kitchens of Rideau Hall and joined her on what, for him, is an ongoing culinary adventure. Longtime GFR Reader will recognize Cameron as a GFR contributor who spent much of his time researching and meeting with some of the regions foremost chefs and food producers. But it turns out he had been engaged in another, deeper, project: a cookbook whose title explains its contents, Vegetarian Vîet Nam.

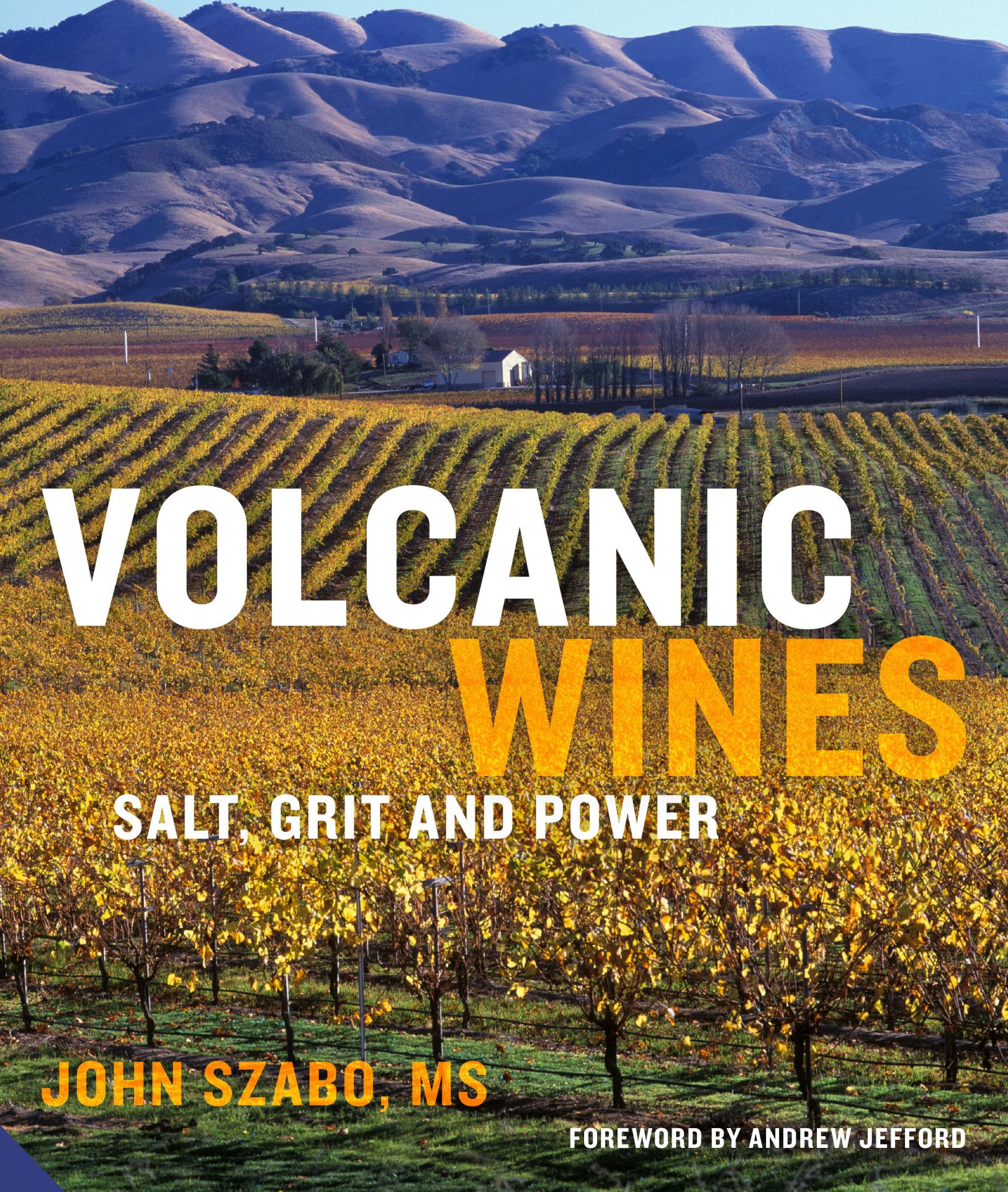

Vegetarian Vîet Nam is the result of years of careful research about an aspect of Vietnamese food that not very well known abroad, and not even that well known in Vîet Nam outside of Buddhist monasteries and festivals. This makes it a particularly compelling book, wit beautiful photography and sensible and straight forward instructions. Cameron’s accounts of his experiences that led to the recipes in the book are fascinating and interest for the book is palpable across the English speaking world.

I spoke to Cameron Stauch recently by Skype to conduct the interview below and find out the hows and whys of Vegetarian Vîet Nam. He talked to me from Vancouver, where he began a book tour of Western North America. He promises he’ll be in Toronto this summer, and I hope to speak to him again then – stay tuned.

This interview has been edited for length, clarity and style.

Good Food Revolution: Why a vegetarian cookbook? As far as I know, you’re not a vegetarian.

Cameron Stauch: No, I am not a vegetarian. Before we moved to Viêt Nam I worked at Rideau Hall. One of the jobs we had there was taking care of dietary restrictions at state dinners, or Order of Canada ceremonies, things like that. I would get a list of people’s restrictions that would run from vegan to gluten-free, allergies, and my job was to make replicas of the main dishes the rest of the team was making. It had to look like the regular dishes so that that person wasn’t singled out. And I would also see if I could mimic the taste. So, when I got to Viêt Nam that process was always kind of in my mind: how can I do this with Vietnamese food, if I have to do it again?

Another reason is, when we got there, my young son, who was three and a half or four, announced that he wanted to eat vegetarian. I think for him it might have been seeing the meat and seafood in the markets on display. He made the connection that the animal he just saw could end up on his plate. But it could also be a thing that he just never liked it.

You know, in Toronto you can go to a place like Sanagan’s for meat, or Hooked for seafood, and find out where the food is coming from. In Viêt Nam and Asia that’s not really often the case. So we just thought, let’s decrease our meat and seafood consumption. We follow a kind of 80-20 rule, where we eat vegetarian about 80% of the time.

And the last reason was my Vietnamese teacher. I took language lessons before we left for Viêt Nam and my teacher explained to me that sometimes she would eat vegetarian because she was a Buddhist. I had that in the back of mind, so when I stared looking around at Vietnamese food, and thought it might be an interested thing to look at, I realized that there wasn’t a resource out there for people to dive into and I thought other cooks, and other travelers, might be interested in Vegetarian Vîet Nam as well.

Good Food Revolution: When I first got the book, I thought it would be quite exotic, but it seems to use ingredients that are for the most part not too hard to find – I mean you can get lemongrass in the supermarket, at least in relatively big cites.

Cameron Stauch: Sure. These are the ingredients that I learned about and saw when I was there learning from the cooks, or when I was in the markets. It’s stuff that I experienced. And these days, with Canadian grocery stores the way they are, you can find most of the stuff that’s in there. There are a handful (or maybe a handful and a half) of ingredients that you might have to go to an Asian grocer to find. Like maybe some of the Vietnamese specialty herbs, or something like fermented tofu or tofu skin. What I tried to do is at the end of some of the recipes I offer variations and substitutions, especially for seasonal fruits and vegetables. For example, if you can’t find taro root for the crispy fired spring roll, I suggest you try celery root or something like that. I am saying, ‘Hey, this is how I experienced this dish, but you have permission to substitute for hard to find ingredients, and these are some that I found have worked pretty well.’ Especially if you want to eat seasonally and locally and that kind of thing. That’s how the Vietnamese eat, so you can adapt the recipes for yourself.

Good Food Revolution: Tell me more about the process for writing the book. Did you just show up at the market and start asking questions?

Cameron Stauch: I guess it was layered in a few ways. Living in Hanoi I had the luxury of being able to visit markets every day. And I wasn’t just shopping for the book, I was also shopping for my family. Just through that I learned about all the different leafy vegetables, the different types of soy products, or rice paper, the different noodles. Once I had learned about that, I started the traveling. I don’t remember if it was by accident or not, but I learned that some of the street food vendors, especially in the Centre and the South of the country, would switch from meat and seafood dishes to vegetarian versions when it was a full moon or a new moon. It would happen every two weeks based on the lunar calendar. Once I learned about that, I would travel to wherever I was going a few days before, and go to the markets to eat the non-vegetarian stuff and then come back on the full moon or new moon and see who was serving vegetarian stuff and try and figure out what they did differently. Was the garnish in the bowl different? How different is the flavour? That was really helpful to me, as opposed to just visiting restaurants.

Good Food Revolution: You lived in Viêt Nam for several years, and as a trained chef you must have soaked up a lot of the country’s culinary traditions. Did you establish a groundwork in Vietnamese cuisine and then decide to write the book, or was it all part the same process form the beginning?

Cameron Stauch: I think I did, from the beginning, but I din’t think I was doing it purposefully. When I arrived in Viêt Nam to live, I had been there twice before on short trips of three or four days, when we lived in the region. That wasn’t enough to get any kind of foundation, but I always try to learn about the food and the culture of someplace were going to live in various ways. Like I said, I took Vietnamese lessons before we moved there, and continued doing that. I started reading about Vietnamese culture by reading novels or history books or travel guides. And as far as the food goes, I really didn’t start working on Vegetarian Vîet Nam until after about a year after we got there. I wanted to get a foundation by going to the markets every day and trying street food. The more you experience something, the more you get that extra layer learning. Then something happens when you go back to a place and you see the cooking with trained eyes. You think, I’ve already seen that, but what’s that? I was lucky to be able to go back to cities many times, at different parts of the year to see if the food was different in, say, November versus March.

Good Food Revolution: You also learned quite a lot by studying with Buddhist monks and nuns, right? How did that work?

Cameron Stauch: I had a kind of fixer, really more like my translator. I would find out about something or someplace, by reading about it online or something, and want to contact them but my Vietnamese was good enough to write a long letter, so this young Vietnamese woman would phone them or email them and explain that I was a Canadian chef who wanted to learn about vegetarian Vietnamese food for a book and could I go and spend a couple of days with them. They were always happy to welcome me. The only time I had trouble was when one nunnery said they wouldn’t allow me to come because I was a man. But they said they wold take me to the next-door monastery.

Good Food Revolution: That sounds like fun and it sounds like they were pleased to show you the way they cooked?

Cameron Stauch: It was great. There was one lady who had written a book about the cuisine of her home town, Huê. It had been translated to French, because she had a connection to some Belgians, but that was about it. So helping to share the vegetarian side of Vietnamese food, which is important to them for ethical, moral and spiritual reasons, was something they wanted to do. And it was important to me, in the beginning of the book to share that aspect of vegetarian Vietnamese cuisine and explain where the food comes from.

Good Food Revolution: OK, so you’re in the markets, or learning in a monastery. Eventually you have to go home and try and recreate everything. How did that go?

Cameron Stauch: In general, it was fairly easy. I think that had to do with being a trained chef. I had to do a lot of measuring with my eyes when I was being shown something. For them measurement is about what it feels like in their hand: a pinch is this much, and a handful is this much. And I had the advantage that we had in our household a part-time lady who was a nanny and cleaner and we had a part-time lady who was a cook. They would sometimes assist me, although they didn’t make anything because they didn’t know very much about vegetarian Vietnamese food because they were from the North. They know a little bit about it because sometimes the pagodas they would go to would have an occasion like the head monk’s birthday, or Buddha’s birthday and there would be a big vegetarian meal for everyone to have, and they would go and help out. So, anyway, I would make the dishes and then ask them to sit down and feed them to them and ask them what they thought. And they were honest with me! Sometimes the response was, ‘No, it’s not there. It’s kind of there but not really.” Other times they would say things like, ‘This is really good, it’s just like meat version.’ So, it was really good to have them as tasters.

Good Food Revolution: You were working on new things.

Cameron Stauch: Yes, some of the things I wasn’t familiar with would be fermented tofu and tofu skin, fresh and dried. They were really new to me and I really fell in love with them for both the flavour they can add and all the things you can do with them. It’s pretty neat.

Good Food Revolution: I know it’s early days and the book has just come out, but I feel like there’s already a buzz about it. People are interested. And you have some pretty impressive blurbs on the cover by heavy hitters like Andrea Nguyen, Naomi Duguid and Fuchsia Dunlop.

Cameron Stauch: It’s great.When we were putting together the book I just kind of had the attitude of if these are people I respect and I look to for culinary guidance I’ll approach them and the worst thing they can do to me is say no. Happily they all said yes. One of the endorsements, that I am really proud of, is from Sister Chân Không. To receive a message from that order, and to hear that they want to sell the book at their monastery, meant a lot to me.