Winemaker António Maçanita of Fita Preta fame is much in demand as a consultant to many wineries throughout the Iberian Peninsula, but it is back in his homeland of the Azores that his heart truly lies.

A few years back he embarked upon a hugely ambitious project to reclaim many of the lost vineyards of the Azores, vineyards that have, in many cases, been abandoned for centuries.

The enormity of this undertaking cannot be fully understood with seeing these ancient vineyards first hand, so last year I flew to the island of Pico with Antonio to observe for myself the fascinating story of the Azores Wine Company.

Good Food Revolution: So although you make wine all over Portugal, you are originally from the Azores, and hence you decided to come back and make wine there. What do you remember of the wines of your youth?

António Maçanita: Back then wines in the Azores were mostly “hybrid-foxy” red wines, served in the taverns or a extra-dry kind of sherry/fino style often used as an appetizer. Both still exist but now dry mineral whites are back.

GFR: Your first winemaking project in the Azores was in San Miguel… planting Cabernet Sauvignon and Durif grafted onto American rootstock… When was that, and what did you learn from that experience?

AM: You are not supposed to ask that :-). It was in 2000, I was 20 and I learned that I was young and foolish.

I wanted to start getting my hands dirty, and managed to convince a group of friends to go and graft a vineyard from an uncle of mine. The result was a disaster and the “salty winds” burned everything. I learn that you don’t f*** with salt and the ocean winds (excuse my French)

GFR: The Azores have a seriously long history when it comes to the production of wines, a history that you delved into quite deeply when doing research for your project. How old are the earliest known vineyards on the islands?

AM: The first vineyards are from the late 1400s. But the huge increase was in the 1600s The golden era was in the mid 1800s when all of Pico Island was vineyards. It was the base of the economy for both Pico and Fayal island and important in the other islands.

GFR: How big was that Azorean wine trade back then, and where is it at today?

AM: Production in 1852 was almost 10 million litres, but with powdery mildew arriving in 1853 and then phylloxera in 1857, production dropped all the way to 25,000 Liters in 1859, never to get back on its feet.

Exports in the 1800’s was mainly to North America, Brazil and to the Russian Czar’s. Nowadays we have a total production of close to 250,000 liters, and sales are 90% local. But this is about to change 🙂

GFR: So it basically became impossible for grape farmers to make a living due to powdery mildew and then phylloxera? That’s quite the double whammy? It’s no wonder so many gave up on it!

AM: It was a calamity and although the people didn’t gave up easily, after a while it was no longer possible to survive. Pico and Fayal Islands lost half of their population during this period to the American continent.

GFR: And you discovered that much of the wine produced back then was actually shipped to the US and sold as Madeira? Where did you find evidence to back this up?

AM: Ship logs in Providence and Boston, with Barrels coming from Pico Island documented as “Madeira Wine”. We also discovered a letter of a governor of madeira dated in the late 1700’s prohibiting the importation of Azores wine to Madeira.

GFR: Having travelled to Pico and seen the development of your vineyards I was astonished at the sheer scale of the project. Please explain to our readers exactly what you are doing there, reclaiming those ancient vineyards from the jungle!

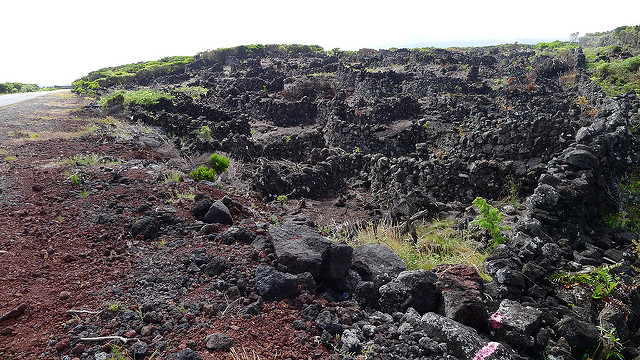

AM: Pico Island on the late 1900’s had between 3000-6000 hectares and now we have only 250 ha producing. After this abandonment, this vineyards were occupied by vegetation. But the ancient walls of lava rock built to (to protect the grapes, for the ocean winds (currais) are still there. What we are doing now is recovering this structures, by cleaning the “jungle” and replanting our indigenous grapes.

GFR: Now this has to be a rather costly undertaking?

AM: It is very expensive and it would be prohibitive if there weren’t incentives from both the EU and the regional government to do it.

The amount of effort that it must have taken to originally construct these small vineyard plots is staggering.

GFR: The vineyards themselves are unique in their construction. Really quite remarkable. How would you describe them to our readers?

AM: They say an image is worth a thousand words, so will send some. But explaining it, we need to go back in time and think of this geologically young volcanic island, where soils were broken rock, over a lava bed.

To be able to access the soil, they had take the rock out of the soil and organize it, then they would have to break the lava bed, and plant vineyards in the rack of rocks. The result is this vines, planted in rock cracks and surrounded by stone walls called “currais” that look like fortresses.

GFR: Hand carved through solid lava? That sounds like a lot of work?

AM: If we are hungry, man finds a way. That is why this vines represent the relentlessness of a people and the capacity to strive even in the hardest conditions. This is what made it eligible to be one of 14 vineyards in the world that are now listed as a UNESCO World Heritage sites.

GFR: I heard it said that in the Azores the best vineyards are located where you can hear the crabs singing. Is there any truth in this? One would imagine that the salty spray would burn the vineyards?

AM: Salt burns everything. So why do we plant so close to the ocean? It is the place where you can ensure more sunlight hours. Due to the cold and humid winds that come from the oceans, entering land and climbing the island there is an almost permanent cloud “hat” that blocks out the sun. It is only in extremities close to water that you are always with direct sun.

And here you can see one of the biggest problems that can face the Azorean vines… the notorious “tempestade” from the Atlantic.

GFR: So how do they possibly weather the storms? the “tempestade”?

AM: This is where the “currais”, stone walls come into play, blocking the salty winds from burning the vineyards.

Winemaker António Maçanita walks his vineyards with his Ontario importer, Bernard Stramwasser of Le Sommelier.

GFR: The white grapes you are working with are unique to the Azores. Most of our readers are probably unfamiliar with the varietals. Please tell us a little about them and what each of them bring to the glass?

AM: All the white wines are very fresh, mineral and saline. If we had to compare it with other styles of wines, they are similar to – dry Riesling, Alvarinho from the North or even Chenin and Muscadet in the Loire. But just with a saltier, iodine component that makes them unique.

The three indigenous grapes are:

- Arinto dos Açores (exclusive to Azores so distinctive and not related to mainland Arinto), this is the one with most texture and acidity, it is very bright and pure;

- Verdelho (same as Madeira, different from mainland Verdelho), is the juicier of the three, with some fresh tropical notes, but still tense and fresh;

- Last but not least, Terrantez do Pico (exclusive to Azores), slightly floral, is the more saline of the three.

GFR: You also work with a few red grapes… I thoroughly enjoyed that rosé! Tell me more about your plans for red varietals?

AM: When I started there was no real strategy for reds since the whites are so incredible and unique. But in 2014 we had some red grapes from one of our partners and we used them, and it is simple but fantastic. Fresh reds fruits, peppery, saline, light colored. Everything I feel like drinking nowadays. Like you.

We have been testing since 2014 with Saborinho grape that is one of the indigenous reds (aka Tinta Negra in Madeira, Molar de Colares in the mainland) and soon we will have a few bottles. But also Bastardo and others (aka Trousseau) were also part of the early plantings.

The abandoned vineyards under the canopy of trees look akin to something from an Indiana Jones film.

GFR: I was quite impressed by the overall quality of the co-operative… although the wines were safe, they were definitely drinkable… I know that I drank a fair bit whilst I was there!

AM: Very true, the Pico cooperative has gone a long way in quality, the wines are very fresh pure and good values. Also something you can feel in every producer is the “terroir” imposes it self and you get the same saline, iodine effect whatever the producer;

GFR: It’s obviously not just me who has a soft/hard spot for your wines, as your press has been most favourable, hasn’t it?

AM: This has been a fantastic ride, because when we started recovering the almost extinct “Terrantez do Pico” and tasted and just thought this so unique, indigenous grape, taste where it comes from, and the challenge, was really just to carry this in to a bottle unharmed. When wine-geeks like me, let it be critics, sommeliers, or consumers started tasting these wines, I think everyone had the same feeling. And the press has been incredible. Last year we broke all the records of the region, and of some other more well known regions.

GFR: Antonio, thanks so much for speaking with us. We hope to see you in the Azores again sometime soon!

AM: My pleasure, you are officially invited the inauguration of the winery in 2017, but I hope to see you there sooner.

Antonio’s Azores Wine Company wines are represented in Ontario by Le Sommelier.

Le Sommelier are a Good Food Fighter.

Please support the businesses and organizations that support Good Food Revolution.

Edinburgh-born/Toronto-based Sommelier, consultant, writer, judge, and educator Jamie Drummond is the Director of Programs/Editor of Good Food Revolution… And he cannot wait to return to the Azores. A very special place indeed.