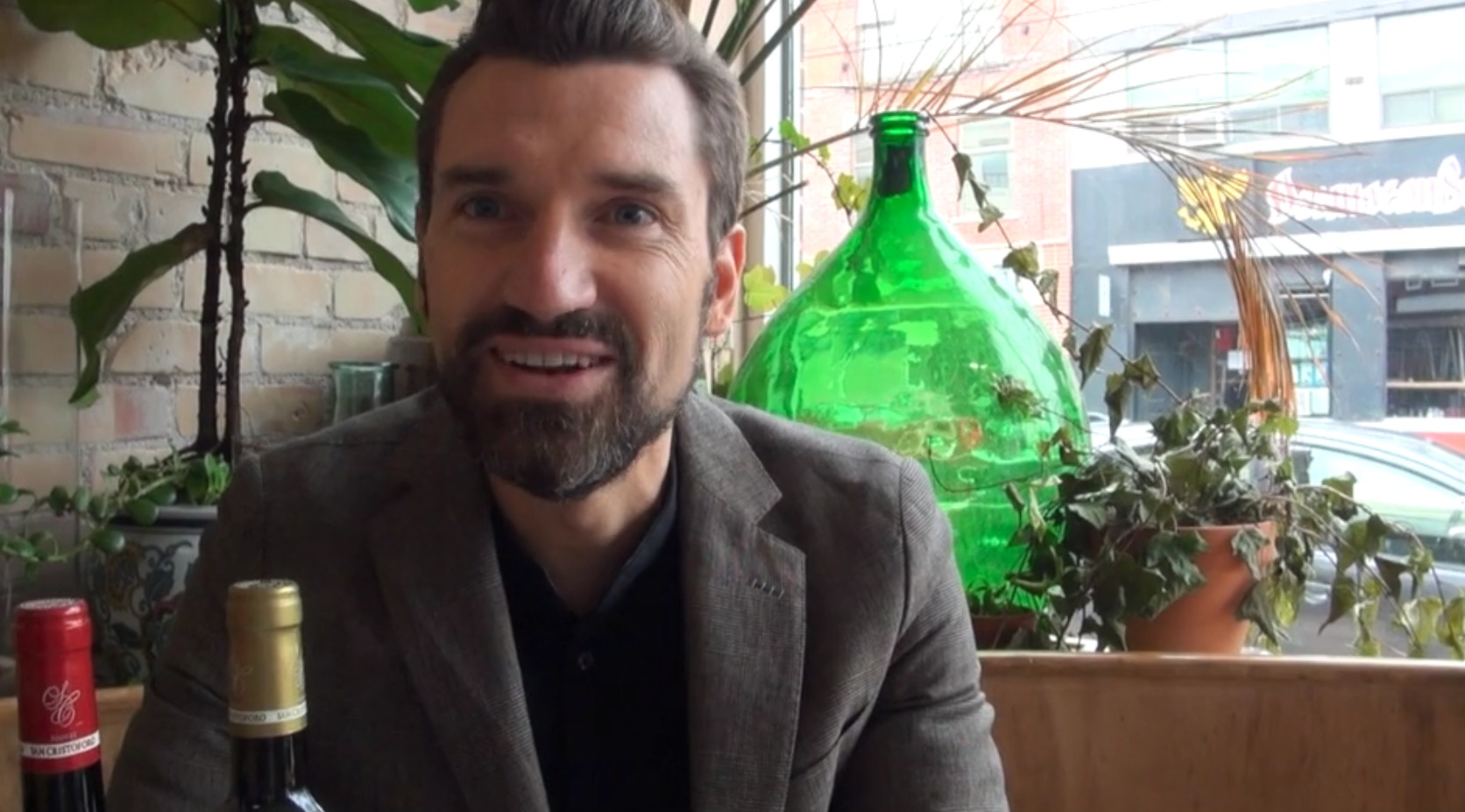

Malcolm Jolley finds out why the rosé wines of Tavel are in a class of their own.

Before I went to Tavel, if you asked me what was the defining character of the rosé wines of the region, and if I answered honestly, I would have said something like, “They’re the ones that are more expensive than the others.” I might have added that they were generally speaking better than the others too, or at least with higher price came an expectation of superior quality that was usually fulfilled Now, I know some of the reasons why all of this is the case. In January I was a guest of the Syndicat Viticole de l’Appellation Tavel along with a delegation of Canadian journalists. We toured the terroirs and wineries of the region and met some of the winemakers, either at tastings or meals or at their wineries. This post is a broad summary and overview of what I learned about Tavel.

Tavel is a pretty old stone built village in Provence just north of Avignon, and many of the wineries of the region are actually in town with the vineyards surrounding it. It’s not a very big area and there are between two and three dozen producers, plus however many growers for the local co-operative. It is more or less right across the river Rhône from Châteauneuf-du-Pape and shares with that region the three basic types of terroirs: sandy, river stones (galets roulés) and limestone rocky soils. The grapes grown in those soils are more or less the same, with black Grenache most often being the dominant varietal. The two regions sort of compliment each other: while it is forbidden in Châteauneuf to make rosé from grapes gown in the AOC, it is forbidden to make anything but rosé from grapes grown in Tavel. (Many Tavel producers also make white and red wines from grapes grown in neighbouring Lirac, so it’s not like thy don’t know how.) Tavel wines have been noted since the Middle Ages, and enjoyed the praise of kings and popes for being lightly tinted red wines. It’s only since the beginning of the last century that they have been made as rosé wines, or that rosé wines were classified as their own thing (due largely to the efforts oft he producers at Tavel).

French laws prohibit the making of rosé by blending red and white wines, but red and white grapes or their juices may be (and are) before fermentation. Tavel wines are “bled” away from contact with the skins of grapes after a longer time than most rosés and so have a darker tint and correspondingly more tannic structure than many other rosé wines. This is both a point of pride and worry to the Tavel producers, explained our host Sandra Gay. Gay, who is the director of the Syndicat, says that Tavel faces the stiffest competition, especially in France, from lighter hued, salmon coloured wines from Provençal and the Southwest. These wines are cheaper and are designed to be drunk on their own, as an aperitif. The effort of the Syndicat is to educate consumers that Tavel is not just meant as an aperitif wine, but one for the table. The producers of Tavel want to position their rosé as un vin gastronomique.

In the next post, I’ll report on how the producers of Tavel made their case.

Malcolm Jolley is a founding editor of Good Food Revolution and Executive Director of Good Food Media, the company that publishes it. Follow him on Twitter or Facebook.

Malcolm Jolley is a founding editor of Good Food Revolution and Executive Director of Good Food Media, the company that publishes it. Follow him on Twitter or Facebook.