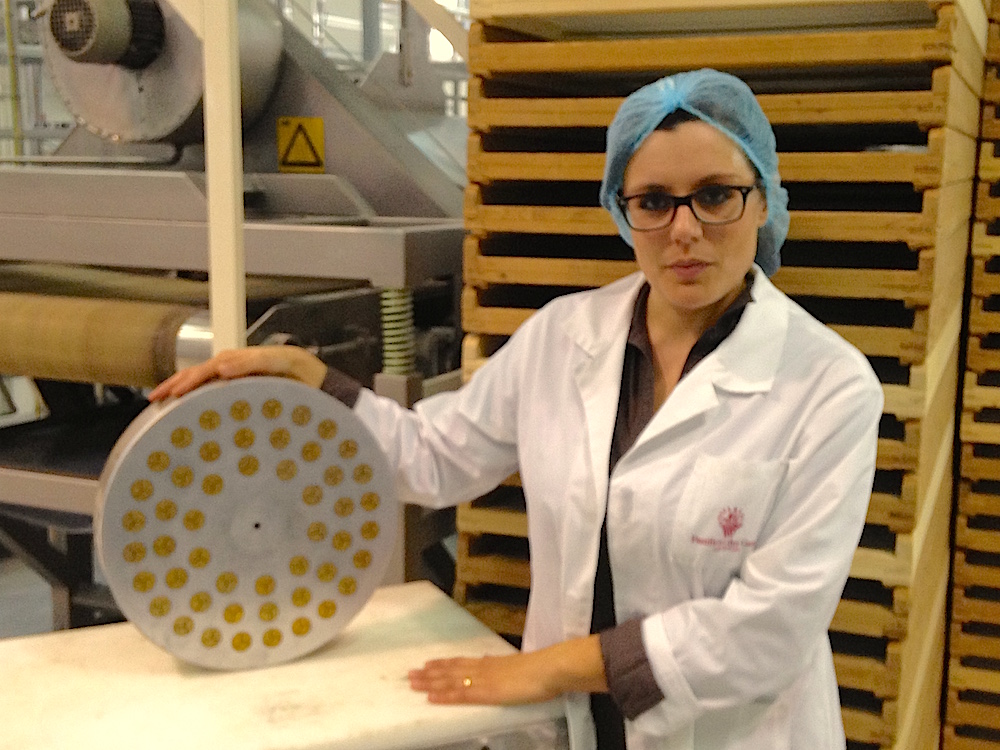

Numzia Riccio leads the delegazione Canadese through the labyrinth of robotic machines at Pastificio dei Campi. All manner of artificial intelligence and precise mechanical movement is expended, at no doubt great cost, in the pasta factory off an alleyway in Gragnano, for the purpose of bringing the past into the future. Riccio is head of Quality Control at dei Campi and she shows us everything that happens along the line with quiet pride. The group of giornaliste from across Canada murmurs in a mix of English, French and pigeon Italian in admiration, not just for engineering of the machines that use lasers to replicate the labours of generations of Campanian women making pasta since Roman times, but also for the calm industry and doughy smells in this warm sunlit room.

Before we were handed over Nunzia Riccio for our factory tour, the team of Canadian food writers were prepared with a lesson on the history and future of pasta by her colleague Margarita Forglia. We were guests of the Italian government and flown to Naples to learn about the DOP and IGP foods with which the republic, still battered by the economic shock of 2008-9, hopes to increase exports. Forglia, who works in Pastaficio dei Campi’s marketing department, explained first how the town of Gragnano became, since the first recorded mention of pasta making there in the Middle Ages, the world’s capital of wheat noodle making.

Gragnano sits between the Lattari mountains that make the spine of the Amalfi Coast to its south and Mount Vesuvius to its north, with Naples beyond. Winds from the Mediterranean blow constantly inland regulating the climate, giving the town a Goldilocks-moderated environment that’s never too hot, too cold nor too wet for the slow and steady drying of pasta. As part of the old Kingdom of Naples, Gragnano milled the semolina wheat of Puglia and made pasta for all the Mezzogiorno from royalty to commoners. By the 19th Century Gragnano’s craft had been industrialized, and the new factories on the Via Roma were exporting to the new unified Kingdom of Italy.

Since this heyday, the small and medium sized pasta producers of Gragnano have lost their preeminent market share to the giant producers of cheap pasta that dominate supermarket shelves in Italy and abroad. To counter the decline, the producers in the town set-up an ‘IGP’ (Indicazione Geografica Protetta) which guarantees pasta products are:

Since this heyday, the small and medium sized pasta producers of Gragnano have lost their preeminent market share to the giant producers of cheap pasta that dominate supermarket shelves in Italy and abroad. To counter the decline, the producers in the town set-up an ‘IGP’ (Indicazione Geografica Protetta) which guarantees pasta products are:

1) Made within the city limits of Gragnano;

2) Made with the mineral rich water from the nearby Monti Lattari; and (maybe most importantly)

3) Made to shape with bronze dies.

Forglia stressed the importance of bronze dies to make proper pasta. The dies are the plates through which pasta dough is extruded to give it shape, from a simple tube of spaghetti to any number of complicated geometric patterns. Large scale industries producers coat their dies with Teflon, which both increases the rate of production, as the dough passes through the holes that much more quickly, and increases the longevity of the die, since the Teflon coating can be easily replaced.

The trouble with Teflon is that it’s smooth and makes a noodle with an even surface. That’s great for factory productivity but lousy for picking up sauce. Bronze is ancient amalgam that sets imperfectly. Forglia’s lecture got experiential when she passed around two handfuls of spaghetti: the bronze die Pacificio dei Campi ones were rough like sandpaper to the touch. The industrial ones, made from a well known global brand, were as smooth as plastic.

Forglia asked if we could perceive another difference between the two sets of noodles. She meant the colour: the dei Campi product was much paler, almost taupe compared to the golden hue of the industrial brand. Neither, as is the tradition of true Southern Italian dried pasta, contained eggs. So where did that yellow tint come from? Maillard effect, Forglia explained. Industrial pasta is flash dried and the extreme heat required to expel water instantly caramelizes some of the natural sugars in the flour, which ultimately alters the taste of the product. The Pastificio dei Campi pasta’s pale tint was a result of their slow, warm and (relatively) humid drying process.

When we toured the factory, Nunzia Riccio showed us the drying rooms where pasta took a full day, or even two, to dry. The intent is to replicate the traditional method of drying pasta outside, as one would laundry. Long noodles are hung over racks like ribbons, and short ones spread out on stacked wooden trays. The temperature and humidity are controlled to mimic Gragnano’s gentle Mediterranean climate, and the rooms smell gently of dough.

Margarita Forglia gave us a third, and last sensory test for the quality of dried pasta. She opened a new box of dei Campo pasta, from a shelf in the test kitchen in which she held her demonstration, and passed it around. Did we notice anything in the box other than the noodles, she asked? Yes: on the sides and coating was a white powdery dust. Pasta made from high quality wheat, roughly extruded from bronze dies and then dried properly, Forglia explained, will give off a residue of fine starch as it tumbles around in its package. The dust is not merely an indicia of well made pasta, but it’s also desirable because it acts as a natural thickener to the pasta water, a splash of which is always added to a finished dish.

In summary, Margarita Forglia’s three part test of good quality dried pasta is as follows:

1) Does the pasta feel rough to the touch?

2) Is the pasta pale in colour? And

3) Is there starchy residue in package?

If you look closely you’ll see a castle overlooking the Pastificio dei Campi factory in Gragnano near Naples.

All the lessons in Gragnano IGP pasta was good stuff, but we wondered what made Pastificio dei Campo different from any of the other Gragnano IGP producers? The answer, we were told, is in the name; it roughly translates as ‘pasta factory of the fields’. To be specific, over 70 semolina wheat fields in Puglia. There, the fields’ farmer-owners contract exclusively with dei Campi, which monitors agricultural practices closely: they ensure the farming is organic and sustainable with a focus on the health of the soils. The Pugliese farmers must adhere to a three year system of crop rotation, whereby in the second year the fields are planted with nitrogen fixing beans (a natural process of fertilization), and in the third they are left fallow to rest before once again being planted with wheat. As a result, Pasta dei Campi must pay their farmers three times the price for their already premium organic wheat. The wheat is, of course, made from heritage varieties which trace their origins to antiquity.

Not surprisingly, the healthy soils of Pastificio dei Campi’s fields make healthy wheat for healthy flour. At over 15% vegetable protein, Pastificio dei Campi’s pasta is cleared by USFDA regulations for import. All industrially made Italian pasta (often produced from Canadian Durham commodity grown wheat) requires additives and nutritional supplements to enter the American market. Margarita Forglia speculates, along with her colleagues in Gragnano, that much of digestive and metabolic trouble that has caused North Americans to adopt a gluten free diet stem from large scale and chemically intensive agricultural practices rampant in large scale commodity farming in Norht America. In particular, Forglia thinks that the long periods of time commodity grains are stored, sometimes for years as they transported across the world, leads to spoilage and the development of toxins like anthocyanins. However credulous these health claims may be for fresh wheat, there is at least a rock solid case for their superior taste. And Pastificio dei Campi continues to grow its share of the market among the cognoscenti from Turin to Tokyo to Toronto.

Pastificio dei Campi pastas are distributed in Canada by Lugano Fine Foods, and found in Toronto at gourmet shops like Cumbrae’s.

Malcolm Jolley is a founding editor of Good Food Revolution and Executive Director of Good Food Media, the company that publishes it. Follow him on Twitter or Facebook.

Malcolm Jolley is a founding editor of Good Food Revolution and Executive Director of Good Food Media, the company that publishes it. Follow him on Twitter or Facebook.