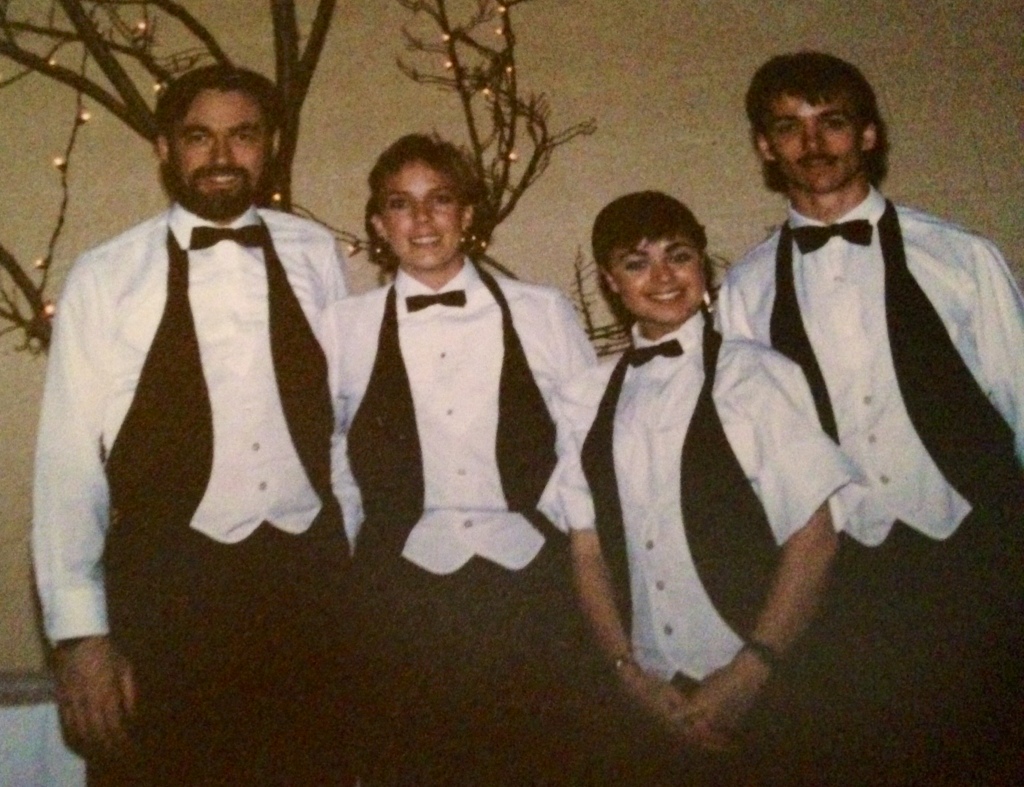

A recent picture of Kevin Gallagher enjoying the summer air at the annual Men In Pink event alongside the subject of a upcoming Old Hands Piece, Mr. John Maxwell of Allen’s on the Danforth..

In the sixth of our burgeoning Old Hands series we probe the memories and minds of some of the founding fathers and original influencers of Toronto’s restaurant scene.

This week sees the turn of a gentleman known as most as Kevin Gallagher, to some as Mr. Mildred Pierce, and to me as probably the only fellow I know who actually looks damn good in a bow tie.

Over his years in the industry Kevin has been a mentor to many, and an inspiration for us all. What with his busy schedule running Mildred’s Temple Kitchen with wife Donna Dooher, we were delighted that he was kind enough to sit down with Good Food Revolution for a lengthy interview.

Ladies and Gentlemen, I give you Mr. Kevin Gallagher…

…

Good Food Revolution: Hello Kevin. Now how long have you been involved in Toronto’s hospitality industry and where did you get your start?

Please remind us of your history in the industry?

Kevin Gallagher: My culinary career really began in London in the mid-seventies with a job as assistant warehouse manager for the Food Hall at John Barnes, a small department store belonging to the John Lewis Partnership. At the time, the Partnership was refreshing their Waitrose brand of grocery stores and using the John Barnes Food Hall as something of a prototype.

It was not at all large by North American standards but offered a great variety of product and very knowledgeable and enthusiastic staff – the greengrocer went to Covent Garden daily, the fishmonger to Billingsgate; cheese was selected and aged in house and we maintained an enormous selection of goods, domestic and exotic – jams and chutneys, soups, crackers, pickles, olives, biscuits, frozen foods and on and on.

As my palate had been stimulated by six months in France and Italy, I was completely swept up in the experience. Even the cafeteria served excellent British cuisine (not an oxymoron).

When I returned to Canada, I was able to get a position as a waiter with the Hayloft Restaurants in Ottawa. The Hayloft made a practice of hiring inexperienced staff and training them, so I spent several weeks learning how to carry a tray, open a bottle of wine and set a table before a ever served one.

I was with the Hayloft Restaurants for a couple of years as server and bartender, then with a few other Ottawa restaurant operations. I even managed a disco for about six months, which greatly increased my appreciation of opera. One of my co-workers at The Hayloft was Donna Dooher; Donna and I were married in 1980 and we eventually became business partners as well.

In 1981, I took a management position with the Mexicali Group. Tex-Mex Cuisine was practically unknown in Canada at the time. It was not unusual to have to explain to guests what tacos, nachos or even margaritas were. The only ethnic foods people were familiar with were Italian and Chinese and when I came to Toronto in 1983 to manage Hernando’s Hideaway, their restaurant here, it was one of two places that served nachos and tacos.

I was with Mexicali Group until 1987 when I left to work with Ms. Dooher at Avant-gout Catering which she had started the year before. I managed the “front” of the operation while Donna designed menus and ran the production. We offered a wide range of catering – social, corporate and film. Avant-gout operated until 1994 when we stopped catering to focus on our restaurant Mildred Pierce that we had opened in 1989.

We operated Mildred Pierce for eighteen years, closing in 2007. In October 2008 we opened Mildred’s Temple Kitchen and that’s where we are today.

GFR: And although this is a huge question, what are the most significant changes that you have seen in the dining scene over the decades? Where is Toronto at today and what have we seen by way of changes since you were in the game?

KG: Forty years ago most meals were eaten at home and dining out was generally reserved for special occasions. There were diners of course, for quick and simple meals during the day, but there was a great difference between those and the fine dining establishments. Social change in the interim, such as fewer women staying at home to cook and more young people living on their own, have created a demand for a middle ground that would feed and connect us in the way the family dinner table had.

At the same time travel and immigration introduced us to a wide variety of new foods and casual restaurant styles, allowing young restaurateurs and chefs to express their passion and innovation in a way that would have been difficult a few decades ago.

GFR: How do you feel about Toronto as a restaurant city? Do you feel as if we are world class in this department or do we still have some way to go?

KG: Toronto, as one of the most cosmopolitan cities in the world, is a great restaurant city. The enormous ethnic diversity has given us food, dining and hospitality on every level of sophistication.

I’ve never been sure what to make of this term “world class”; it seems to be a yardstick without markings. The culinary scene is bound to be different in a young city like Toronto so it’s unproductive to draw comparisons with larger or older centres.

GFR: What with a number of New York Chefs opening outposts in our fair city, what do you think that this says about the evolution of our dining scene, and perhaps more poignantly, global dining as a whole?

KG: Toronto and Canada have been relatively unscathed in the Great Recession, so part of the equation for New York chefs’ expansion has to have been a fairly stable economic outlook. Given the city’s diverse and well-developed culinary scene and proximity to New York it is a logical extension for their brands. There is no doubt that their presence here will raise the city’s culinary profile in the rest of the world.

GFR: Message boards such as Chowhound often bemoan the lack of polished service in Toronto? Do you see any truth in this?

KG: Absolutely.

Too often servers are not committed to the industry, seeing the position as a means to support themselves until their “real” career takes off. They see little advantage in learning the proper skills. Operators often hire in haste and feel they don’t have time to train staff properly, but proper training is essential to providing good service.

GFR: I’m so glad to said that Kevin. I have felt that way for so many years now…

What in your mind makes for good service?

KG: Proper table service is an essential part of good service. It provides a certain easy ceremony to dining and like good manners in any social setting puts guests at ease and makes then feel special, no matter how casual or sedate the operation.

Good service though, really begins at the door or with the first phone call and extends through the whole dining experience. An icy phone manner or a haughty greeting from the host will undermine the efforts of the warmest server.

The floor manager has to take the lead in ensuring that service is perfectly seamless. He sets the tone; it’s his orchestra to conduct. He must appear at ease and available to his guests to see that their expectations are being met – or preferably exceeded. The kitchen too must follow his lead. In this era of the celebrity chef, it’s so easy for the kitchen to lose focus and fail to remember that guest satisfaction is the goal. If the chef refuses to bend, service suffers. You can’t run a restaurant from the kitchen.

Providing good service is teamwork and a common goal.

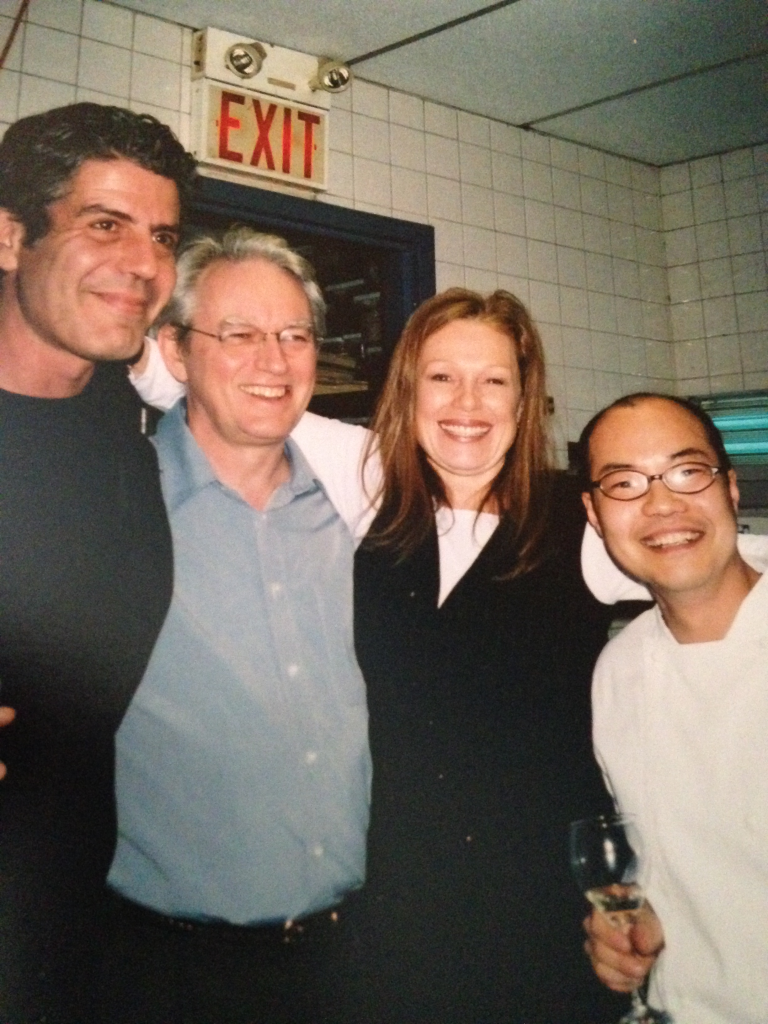

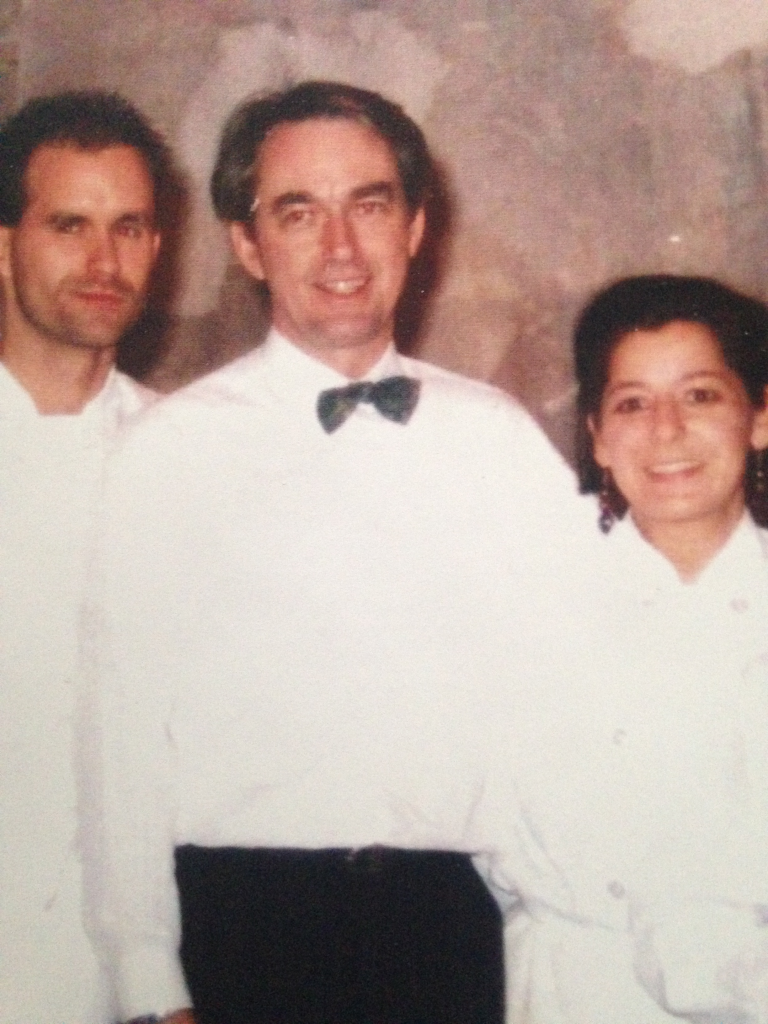

Anthony Bourdain, Kevin Gallagher, Donna Dooher, and Steve Song at Mildred Pierce for the launch party of “A Cook’s Tour”

GFR: Over the years, where have you experienced the best service in Toronto?

KG: A difficult question to answer – recognized as industry people, I know we are often the recipients of more attentive service. Generally I find that the best service has been in restaurants that have good staff training programs like the Oliver & Bonacini restaurants, but the best service I’ve had in recent memory has been at The Chase.

GFR: Does the future of the independent restaurant in Toronto look bleak or blissful from you point of view?

KG: I would hate to say that the outlook is bleak for independents but it is certainly challenging. We are squeezed between the big chains on the one hand, and on the other, the “trust fund restaurateurs”, that is the small operators who have a little money to invest in a start-up location, work very hard and pay themselves nothing.

For the big chains, it’s pretty well all about the bottom line. Their buying power assures them the best prices and if the provenance of their product is very much secondary, their selling prices are impossible to match.

The small operators though are very hands-on, fired by a passion for food, often personally sourcing their raw materials, prepping and cooking to order themselves; they generate huge excitement and buzz in the community.

These small operators are independents too of course, but when inevitably you have to start paying more attention to the bottom line, because you have to make a living, the approach changes. When being an independent restaurateur becomes a career the passion hast to be tempered with all the trappings of running a business – rising prices, increasing bureaucracy. It becomes a challenge to remain competitive and interesting to diners – however; the independent restaurant is the wellspring of creativity in the hospitality and food service industry. We’re not going anywhere.

GFR: “No-shows” can be the death of a small establishment. What do you feel can be done (legally) to combat such situations?

KG: The best way to discourage “no shows” is to engage the guest at the outset when the reservation is made, through a personal introduction, interest in the booking, asking whether it’s a special occasion or a quiet dinner, and what can be done to make it special. Follow up to confirm on the day of the reservation. If there has been a change of plans the party will most often let you know then. Available technology allows us to track “no shows” and ultimately decline reservation requests if it happens too often.

Asking for a credit card number to confirm a booking, other than for a large party, is seen by many as an affront. What are you really saying but “You sound like an undependable person. I don’t think I can trust you to show up.”

GFR: So do you feel that a “no reservations” policy is a sensible solution for a smaller restaurant?

KG: It ultimately depends on the menu price point. The cost of the holding a table for a reservation is reflected in the cost of the meal. The restaurateur has to pay his bills and hopefully make a little for himself. If an inexpensive restaurant can seat a table three or four times in an evening because of a no reservation policy it’s great for everyone.

It has been said that refusing to accept reservations shows a lack of respect for one’s guests, but the precipitous decline in respect for punctuality generally, can make a nightmare of administering reservations in a small restaurant. If a table sits vacant for an hour or and hour and a half because it must be available for a reservation, the costs still need to be covered, hence forty-five dollar entrees.

GFR: How do you feel the recent increase in minimum wage in Ontario impacts the restauranteur?

KG: The increase in minimum wage is another challenge because the industry is so labour intensive and to prepare great food you need to have the staff to do it. Raising the minimum wage raises the bar, bringing all wages up with it. It doesn’t matter whether or not you pay anyone minimum wage, the expectation of a higher wage comes along with a boost to the minimum.

The choice for the independent restaurateur may come down to such things as “Do I buy Ontario garlic and pay someone to peel it or save a couple of hours by buying vacuum packed peeled garlic from China?” Ultimately the increase will have to be absorbed by menu prices.

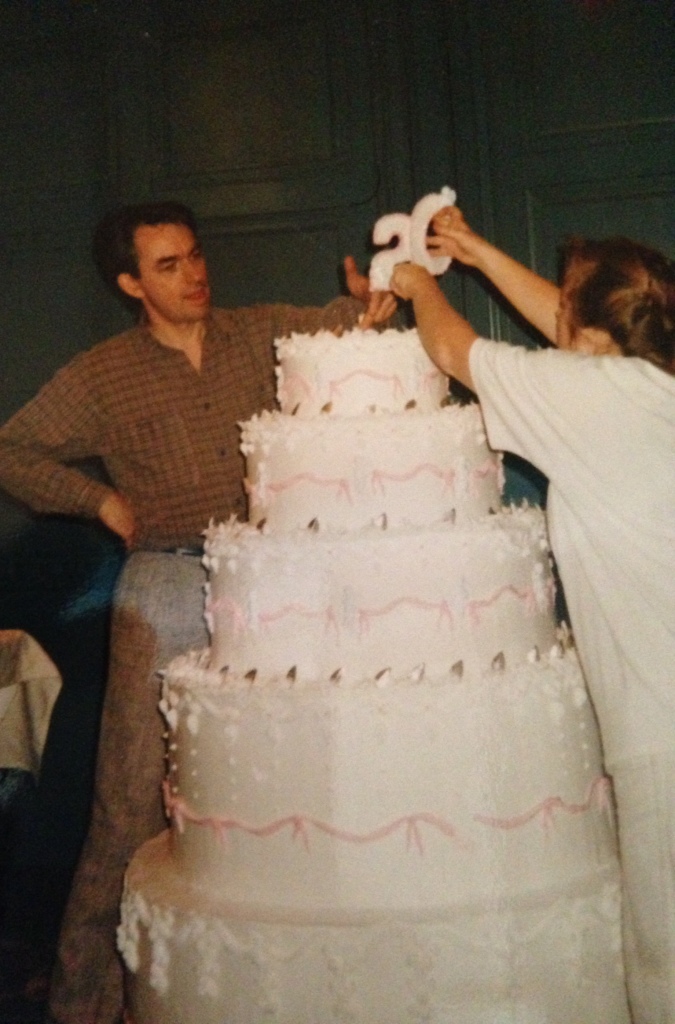

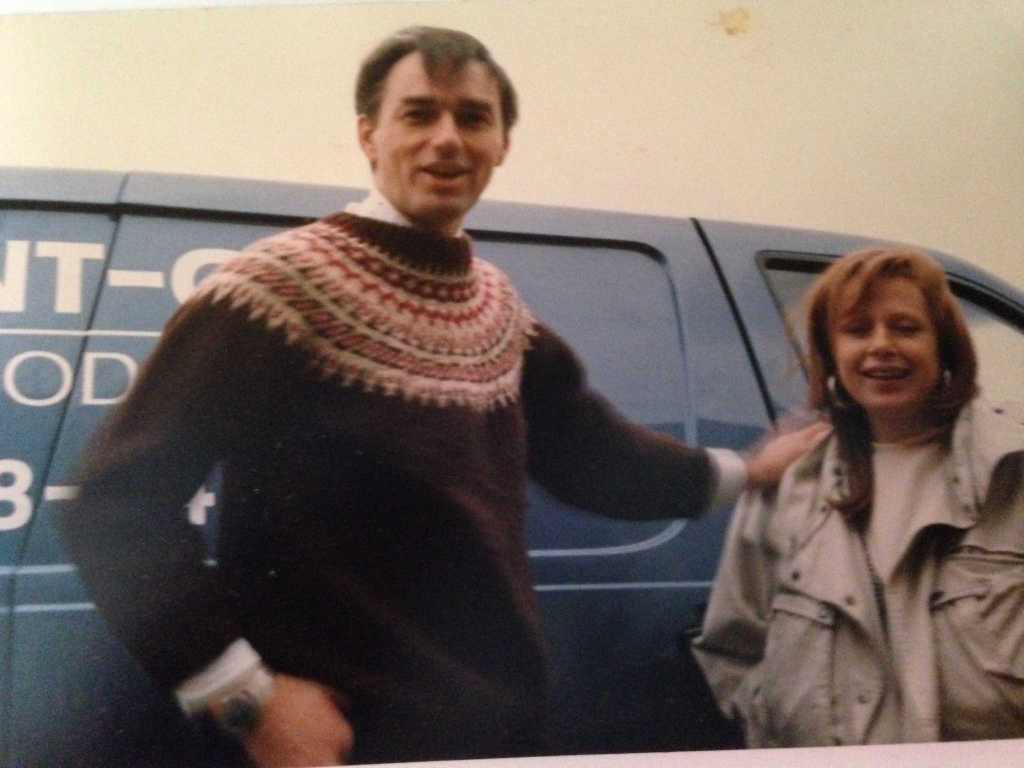

“Donna and I topping off a cake for some company’s 20th anniversary. Cake is styro with twinkly lights inset and shortening and sugar frosting. It was an engineering exercise – not catering.”

GFR: Getting into the area of tips? Do you feel that serving staff should payout something to to the house for breakages and the like? What do you feel is fair or are such expenses just a cost of doing business?

KG: Breakage is often the result of poor handling practices and occasionally negligence but almost always accidental. Handling practices can be assessed and improved and negligence pointed out and disciplined if necessary but taking gratuities to cover the costs is unproductive.

GFR: And what are your thoughts on the recent case regarding Mario Batali settling a lawsuit regarding skimming of tips to the tune of $5.25 million?

KG: There is really no justification for withholding servers’ tips as long as we work with the current system of compensation for restaurant employees. It is acceptable to ask that the gratuities be shared with bartenders, stewards, bussers etc. but not to subsidize the wages of other positions.

GFR: On the subject of Toronto restaurant critics, do you feel that any are worth their salt?

KG: No. They are generally arrogant and rarely objective. I really don’t know whether their intention is to enlighten the reader or just sell newspapers. They seem to have a very limited understanding of how restaurants operate which is unfortunate because the enlightened critique of an operation could benefit both the restaurant and the consumer.

GFR: Very interesting… And how do you feel about the legitimacy of guides like Zagat and its ilk?

KG: As anyone with the price of a meal has the right to an opinion on it, you can’t argue with its legitimacy if it. A rating that is the average of several hundred or a thousand opinions should be a fairly accurate reflection of the food and service of a restaurant and a reliable guide. My only reservation is based on an experience I had about twenty years ago. I had complimented a colleague, the proprietor of a small Queen West restaurant, since retired, on his great ranking in the Zagat guide. “Yeah,” he laughed, “a bunch of us sat around one afternoon, had some beers and filled out ballots.” I don’t believe the practice is in anyway widespread but it has coloured my appreciation somewhat.

GFR: And then of course we have the democratization of food writing… food bloggers… where do you stand on this particular issue?

KG: It’s great to see so much interest and enthusiasm about food – that individuals would take the time to describe in detail their impressions with pictures is amazing to me.

I would just want to eat! The blogs give us a snapshot of an individual’s experience, how menu items are being presented – it’s almost like having a secret shopper. Granted they are usually subjective and sometimes inaccurate but mostly helpful. In the weeks following the opening of Mildred’s Temple Kitchen, the restaurant was the subject of a huge number of blogs, so much so that the newspaper reviews had far less impact than they would have had twenty years ago.

GFR: It appears to me that Toronto goes through very obvious trends in its restaurants (tacos, bacon on and in everything, gooness knows what this week) I’d love to hear your thoughts on this topic?

KG: I do find it rather funny that tacos are so hot right now, because tacos are more or less what brought me to Toronto. But those tacos weren’t “authentic” I’m told and I wonder what the average Mexican might make of these others made with seared duck and a dainty slaw – Delicious, but authentic?

Food trends are cyclic to some extent and as young cooks discover new ingredients and include them in a time-honoured recipe, it’s not surprising that others pick up on it. There is a great deal of pressure to keep up with trends; to stay current in menus, feeling that the guest expects it – but it can get a bit tiresome when that ingredient appears everywhere.

Today you’ll find Kevin at Mildred’s Temple Kitchen, Toronto with his wife and business partner Chef Donna Dooher (another upcoming Old Hands interviewee!)

GFR: And what, in your sage wisdom, do you predict for the future?

KG: Insects – well isn’t it about time? We’ve eaten pretty well everything else.

GFR: Ha… yes… you are not wrong there Kevin.

Food Television has exploded over the past 10 years… how accurate a portrayal do you feel it paints of our industry?

KG: I rarely watch it. I’m not a fan of the confrontational cuisine that seems to be the basis of most of it and I don’t think it is an accurate reflection of the industry. Most evenings in a restaurant kitchen would make pretty boring television.

GFR: Canadian wines have come a long way since I arrived in Canada 17 years ago. Do you still feel that there is a resistance to them in some quarters? And why do you think that could be?

KG: There is still resistance to Canadian wines particularly with the reds. I believe that part of it is due to the difference in terroir that is displayed in the wine. Prince Edward County, for example, is so distinctively and beautifully represented in its pinot noir, yet people feel that is should taste like burgundy or a California pinot if it’s any good. Much of the resistance still comes from those who are unwilling to taste.

GFR: Kevin, thank you very much for your time… you gave us some truly superb answers.

…

Edinburgh-born/Toronto-based Sommelier, consultant, writer, judge, and educator Jamie Drummond is the Director of Programs/Editor of Good Food Revolution… And he’ll never forget building a wine list in a workshop with Kevin at one of the earlier Terroir symposiums.

Edinburgh-born/Toronto-based Sommelier, consultant, writer, judge, and educator Jamie Drummond is the Director of Programs/Editor of Good Food Revolution… And he’ll never forget building a wine list in a workshop with Kevin at one of the earlier Terroir symposiums.

Loved the photos – such great little snippets of history! Thanks!