Contemplating Caravaggio requires something dark and intense, something almost repugnant. It requires a wine to rival the artist himself, something brooding and bloody and outlaw and seductive.

Caravaggio was trouble. And he was one of the greatest artists who ever lived. This has only recently been acknowledged because Caravaggio, the “antichrist of art,” was so dangerous that he was accused of destroying art. And he was nearly obliterated from history. There are only about seventy surviving works, and none of them had ever showed in Canada until a dozen or so exhibited in Ottawa a few years ago. This event was a landmark of history; the fact I didn’t make it still causes me to weep into my Negroamaro.

Indeed, it hasn’t been for much longer that the genius of Michelangelo Merisi o Amerighi da Caravaggio has been revived. This “other Michelangelo” slept like Lazarus until the 1950s when he was raised from the dead.

To drink with Caravaggio, I choose the Farnese Negroamaro ($8.95 – LCBO #143735). Yes, this plebian classic is probably too silky and delicious for the occasion. I must plead poetic license, for its name means “black and bitter.” Two better words for the soul of Caravaggio’s art cannot be found.

To drink with Caravaggio, I choose the Farnese Negroamaro ($8.95 – LCBO #143735). Yes, this plebian classic is probably too silky and delicious for the occasion. I must plead poetic license, for its name means “black and bitter.” Two better words for the soul of Caravaggio’s art cannot be found.

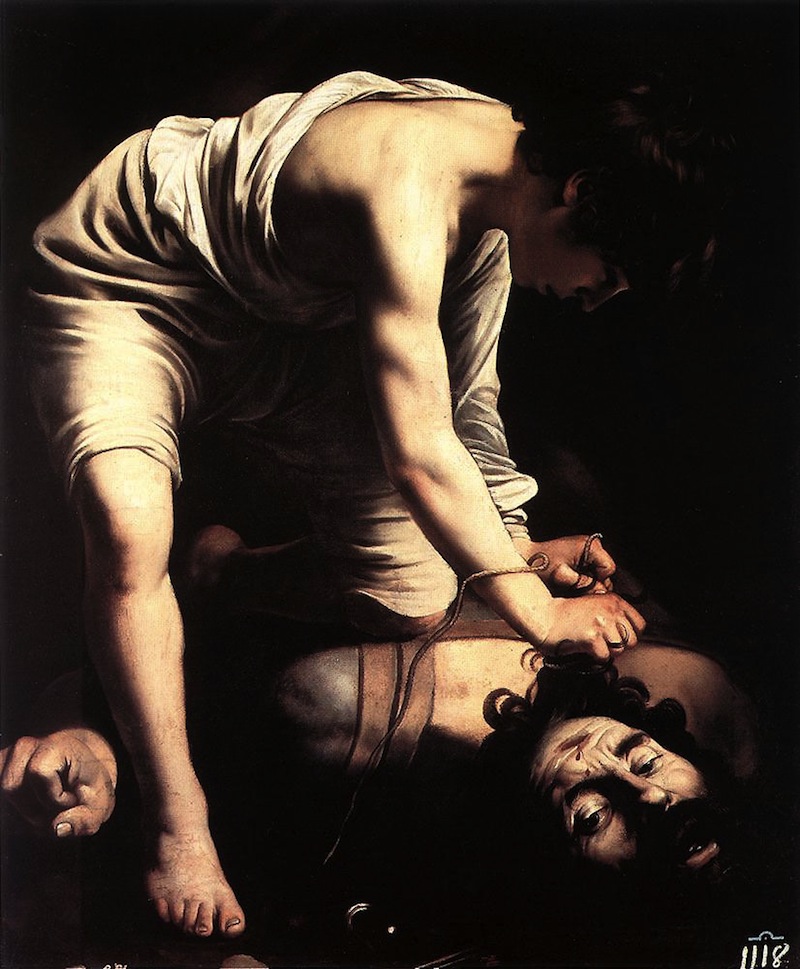

The blackness, as it were, of his paintings is palpable from across four centuries. Caravaggio heeds no traffic signals and marches straight to the edge of the abyss of human depravity. Yet even a shoddily reproduced post card bears witness to how far above and beyond most other talent Caravaggio stands. He is not merely good or great – his talent is almost unfathomable. The technical draftsmanship alone will make your head spin, yet that is matched by other rare gifts. It is the innovative manipulations of light that served Caravaggio’s symbolism of good and evil that are unparalleled through today. Deep within the beauty and perfection of the precision skill itself, there is always something repulsive and terrifying layered into Caravaggio’s work. It dares reveal the beautiful side of evil. It dares confront the evil side of beautiful.

Born in Milan, Italy, in 1571, Caravaggio swashbuckled the streets for just under forty years, waving his sword, slugging back Maltese wine and beating people to a pulp. He threw stones at little old landladies.

He was violent and passionate and mad. In a duel, near the end, he was disfigured by his fellow vigilantes, and possibly blinded in one eye.

The legend of Caravaggio as a renegade remains strong to this day; there is even a line of Maltese wines named after him.

His life was tumultuous; his death mysterious.

Sister Wendy says he died of malaria. Others say it was in prison. Some suggest he drowned.

He lived by the paintbrush, and also by the sword. Safe to guess he died the same way, in some way.

Perhaps the painter is best understood in light of historical context. 16th century Italy was at the epicenter geographically and historically of Catholicism, a Catholicism that had at turns been challenged by, humbled by, or victorious over almost a century of the Reformation.

In the contemporary climate of fashionable rejection of Catholicism, rooted in the impasse of the church’s opinion with our own on issues like birth control, we have perhaps “thrown out the baby with the bathwater.”

The Catholic church historically did much to advance and fight for science, for university and also for literacy and mass education, and it importantly held the torch of art and art patronage. The iconoclasts of the Reformation like John Calvin fought viciously to destroy art and music, and they marauded around smiting and torching the fruits of human creativity wherever they found it. Very little in way of great opera or painting has ever come out of the Protestant branches of Christianity. It’s easy to forget the staggering importance of Catholicism in art history when we have endless reproductive powers – ahem. Our access to prosperity and technology means we can magically create images of imagery to infinity. iTunes brings music to every head on the subway, custom tailored to each person. Art is easy today. We take it for granted. But not long ago, artists were the only means by which a visual record could be kept and their original work was the only chance the populace had of feasting their eyes on something other than the fruits of the plague. The church employed, commissioned, and collected art- a heritage that was collectively enjoyed.

Said plague points to another important aspect of life at Caravaggio’s birth- violence and death and plague and famine were rampant. Death was not sanitized and softened. Without much in way of working medicine, hygiene, and sewage treatment, life and death were savage, and the stench and the terror were part of everyone’s daily bread.

When someone cynically remarks that Caravaggio painted religious subjects because the Church hired him to do so – as if artists should not ever make a living – they are not seeing the whole picture. From here, we see familiar Biblical narratives, appropriately gory as per their subject matter, and masterfully wrought. But Caravaggio had to beg and fight for work because his art was so blasphemous. Seething with underhanded mockeries and hardly a pillar of faith, Caravaggio was nobody’s darling.

Devout art has never been a stranger to darkness – Christian art and literature deals rather frankly with the question of evil. But this was the first time in history that the artist used scenes with severed heads as macabre opportunities for self-portraiture. (He also used mythological scenes such as Narcissus to leave his ghost behind.) Too, religious art was often idealized and devotional. But with Caravaggio, the attentive portrayal of youthful anatomy gives way to saints with filthy feet and fingernails.

“It was an exacting aesthetic,” writes James Camp in his lively 2011 Observer review of Andrew Graham-Dixon’s biography, Caravaggio: A Life Sacred and Profane. “It left out landscape, sunlight, heavenly choirs, healthy cuticles.” When we study his work comparatively, we suddenly notice what’s missing. There are no landscapes, no pastures, no clouds, no gardens. There is nothing but blackness and gloom, to contrast with the light the artist sheds on the disturbing tableaus modeled by dug up corpses. Chiaroscuro is what we call the resultant magnificence of contrast Caravaggio used to stunning effect. “The result altered the DNA of Biblical imagery,” Camp explains. “Gone was the grandeur of a Raphael, the pure blues and unblemished pastures… stooped figures grappled in the gloom.”

It was all this that Caravaggio left out that was just as offensive to ecclesiastical society as what he refused to whitewash or idealize. More often than not, exquisite commissions he toiled over were rejected.

The Virgin was one such example. The Carmelite priests wanted nothing to do with the brilliant masterpiece, The Death of a Virgin. “Mary is not shown in the customary way,” Sister Wendy understates, “ascending to heaven in glory. We are confronted with both a human corpse and human loss.”

That’s one way to put it.

The model for the Holy Mother of God in this spectacular piece of art history is the corpse of a drowned prostitute.

Caravaggio cavorted with courtesans, dead or alive; he boozed and brawled; he was in ongoing trouble with the police; he lived in permanent exile. He killed a man, probably not over a tennis match as the official story went for years, but as the botched castration of a rival to a favourite whore.

There were countless other assaults and attempts at murder, and any rumours of secret homosexuality must be reasonably chalked up to “when in Rome.” Beautiful young boys were for plunder, but they were just the appetizer.

There was wine, gambling, pimping, sex, some haphazard classical mythology, and the occasional fear of God. All of this appeared in Caravaggio’s work. How a clandestine bandit managed to set up his pigments by candlelight and spill his tortured soul is part of the mystery.

You must see this scenario with some kind of tragic Italian opera as the soundtrack, and by candlelight just as the artist would have worked. See, the black and the light in each painting, an exquisite symbolism that transcends the centuries. You can see it in the eerie dance of flames in your glass, the blood red wine flickering glittering lights across the wall.

Lorette C. Luzajic is an artist and writer with roots in southern Ontario’s wine country soil. Native to Niagara, at home in Toronto, her work is inspired by wine, cheese, and bleak post-apocalyptic literature. If you missed her at the ROM or the Ritz, visit her at ideafountain.ca. Photo: Ralph Martin.

Lorette C. Luzajic is an artist and writer with roots in southern Ontario’s wine country soil. Native to Niagara, at home in Toronto, her work is inspired by wine, cheese, and bleak post-apocalyptic literature. If you missed her at the ROM or the Ritz, visit her at ideafountain.ca. Photo: Ralph Martin.